Protestors march on the Golden Mile Beach in Durban on 6 March 2022 as a show of support for the Ukrainian people, and calling for the South African government to condemn the action of the Russian president Vladimir Putin. Photo: Rajesh Jantilal/AFP

As the world watches in disbelief as the war in Ukraine evolves, the adage comes to mind: in every crisis there is an opportunity. As Africa prepares for the inevitable political and economic fallout, it may be an opportune time for some African countries to formulate new political and economic policies that may benefit from a shift in global markets.

Immediate concerns for Africa

While there may be longer-term benefits to target, there are more immediate concerns. African students studying in Ukraine found themselves stranded and desperate to escape. There have been reports of racism and discrimination regarding evacuation measures. Media reports and social media videos have highlighted discriminatory practices with claims of Ukrainian police and security personnel refusing to allow some Africans to board buses and trains heading towards the Ukraine-Poland border. Because of the lack of African embassies in Kyiv, diplomatic interventions were made from African embassies in Warsaw. Calls were also made to the A3 (Gabon, Ghana and Kenya) on the UN Security Council to be stronger in their criticism of human right abuses African students experienced.

The invasion will have detrimental consequences for African households, the agricultural sector, and food security. The overdependence on wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine is a concern as they constitute almost 30 percent of global wheat exports. About 36 percent of Ukraine’s total wheat is exported to Africa. There are fears Russia’s blockading of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports will prevent exporting the remainder of last season’s wheat harvest. Kenya, Sudan and Ethiopia are experiencing rising food prices. With elections later this year in Kenya, a recent coup in Sudan and the ongoing civil war in Ethiopia the elevated wheat prices may fuel anger, leading to insecurity. Rising oil prices will exacerbate the situation as transport cost increase, so too will food prices, creating a vicious cycle.

Natural resource opportunities

After Russia, South Africa is the world’s second-biggest producer of palladium and is positioned to benefit from the sanctions as supply concerns grow. Palladium is an important component used in automobiles and electronics. The precious metal has surged to a seven-month peak due to sanctions imposed on Russia. With many turning to gold as a safe haven, this too may benefit South Africa as a major exporter of gold as the rand has been strengthening due to rising global prices for the precious metal.

With the prospect of Russia turning off the gas supply to Europe as a measure to counter sanctions, Europe has seen a spike in gas prices. One can only assume that contingency measures are being formulated to avoid a potential cut-off in gas supply to the EU. A viable option may be to look South, as Africa has some of the world’s deepest gas reserves and can offset some of the 150-to-190-billion cubic metres Russia supplies yearly.

Additionally, in anticipation of a European energy crisis, analysts have forecast South Africa as an option for European coal plants seeking high-quality coal.

President Samia Suluhu Hassan from Tanzania recently proposed a solution for the EU gas dilemma. “We are looking for markets wherever. Whether Africa or Europe or America, we are looking for markets. And fortunately, we are working with companies from Europe.”

The country has the sixth-largest gas reserves on the continent, estimated at 1.6-billion cubic metres. Tanzania, in partnership with European fuel and gas companies, should develop measures and mechanisms to facilitate the exporting of gas to Europe to fill the potential void and lessen the over-reliance on Russia.

As the continent’s largest gas producer, Nigeria is also moving towards potentially filling the gas void by continuing construction on the trans-Saharan gas pipeline (614km), which will carry the gas to Algeria, then to Europe. The recent signing of a memorandum of understanding with Algeria and the Niger is hoped will expedite this initiative.

While the countries above may be better positioned to benefit in the short term, other countries in sub-Saharan Africa require much more infrastructure expansion if the continent wishes to be more than a temporary solution and become long-term suppliers.

Several African countries with large gas reserves have failed to attract sufficient investment to build gas infrastructure projects that could supply the European market. For instance, Angola, with 382-billion cubic metres of known gas reserves, has been unable to slow a decline in oil and gas production in the last five years. Without the proper investment the infrastructure will not grow or perform optimally.

Mozambique has about 2.8-trillion cubic metres of natural gas reserves, and accounts for almost 1% of the world’s total reserves. However, the continuing insecurity in northern Mozambique, a gas-rich area, has stalled exploration activities on a planned $50-billion project. In this instance, the insecurity in Ukraine should have been the opportunity for Mozambique to becomes a key gas supplier but its own insecurity concerns have thwarted that possibility.

Soviet Union and African liberation movements

Historically, support for the Soviet Union and later Russia was seen as an alternative to Western imperialism and capitalism. Both Angola and Mozambique’s flags are heavily influenced by Soviet imagery with Mozambique having the image of an AK-47 rifle on its flag. The Soviet Union was influential in several liberation wars in the SADC region, namely, Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. More recently, mercenaries from the Russian paramilitary group Wagner have been operating in several countries in Southern, Central and West Africa under the guise of fighting extremists.

The AU issued a statement condemning Russia’s invasion and called for an immediate ceasefire. Kenya’s Ambassador to the UN Security Council was quick to question the Russian invasion and called for respect of territorial integrity and national sovereignty. Gabon and Ghana, the two other African members on the Security Council, followed suit and expressed disappointment over Russia’s actions.

As the crisis developed several African leaders were placed in a difficult position of trying to remain neutral. The two economic giants on the continent, South Africa and Nigeria, delivered relatively subdued and varied early responses. Initially, South Africa did not issue a statement, but after the full-scale invasion the government, called for Russia to withdraw its forces. However, this stern tone in language soon changed to “South Africa remains deeply concerned by the escalation of the conflict in Ukraine”. The Nigerian government chose to note its surprise about the invasion but neither condemned it nor called for a cessation of hostilities. Nigeria did, however, vote to demand the immediate withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine, whereas South Africa abstained.

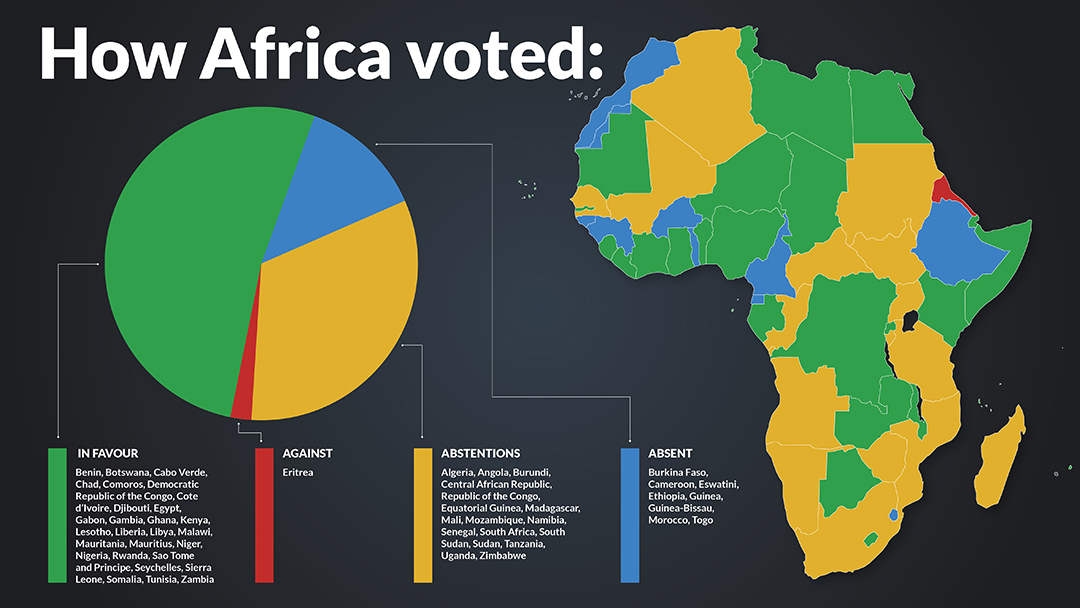

How Africa voted at the UN General Assembly

A UN General Assembly emergency session adopted a resolution calling for the immediate withdrawal of Russia’s forces. African diplomats were divided in their votes.

Out of 54 states:

- 28 – Voted in favour

- 1 – Voted against

- 17 – Abstained

- 8 – No vote recorded

Way Forward

The ensuing war in Ukraine has already impacted Africa with fleeing students facing human rights abuses, fuel and transport price hikes, growing concerns over wheat imports impacting food security across the continent. However, this may also provide some African countries with new opportunities to develop their infrastructure and gain access to new markets. African countries should act on this possibility to strengthen their policy formulation and implementation to benefit all.

This article first appeared in the Mail & Guardian.

[activecampaign form=1]

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.