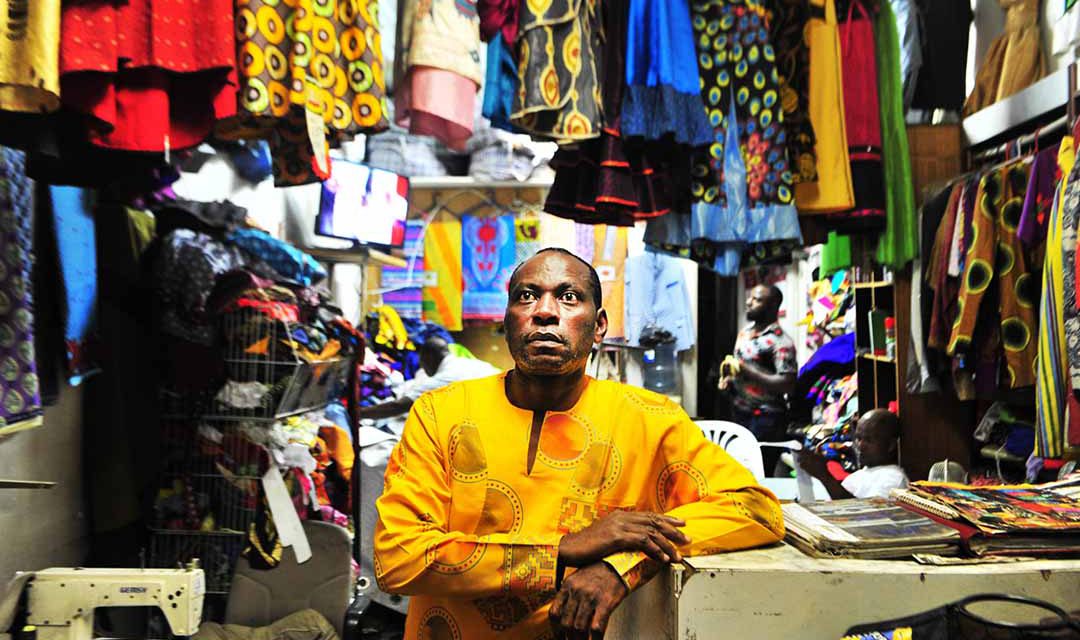

Solomon Owah runs Paradise Outfitters in Orange Grove, a suburb of Johannesburg. He is also an axctive member of a branch of the ruling ANC. He is also president of the Orange Grove Nigerian Association. Photo: Mukurukuru Media

For many Nigerians living in Johannesburg, community organisations offer an important link to their roots as well as much-needed support

Solomon Owah smiles warmly as another of his endless stream of visitors greets him with a handshake and half bear hug at his fashion store in the Johannesburg suburb of Orange Grove.

It’s a balmy Sunday evening and more than half a dozen men chat away among the sewing machines lined up on each side of opposite walls. On one side hangs a television set. Eyes are glued to the set, whose channels alternate between a Barclays English Premiership match and a National Geographic wildlife channel.

Owah sits furthest from the rest, towards a door leading out into the kitchen and another to the bathroom. Facing the main door, looking out onto a busy Louis Botha Avenue, he smiles often and occasionally drops a joke, getting some laughs from the men seated there. Clearly, he is regarded with warm respect and admiration.

Owah runs Paradise Outfitters in Louis Botha Avenue, a main road connecting Orange Grove with other north-eastern suburbs of the city. President of the Orange Grove Nigerian Association and a Nigerian by birth, he now considers himself South African – although he admits that he doesn’t speak the local languages fluently.

A native of Delta State in the west African country, Owah migrated to South Africa in 2000 in search of a better life. He is married to a South African woman who hails from KwaZulu-Natal province. The couple met right here on the streets of Orange Grove and they have two children. In the 17 years he has lived in Johannesburg, he has established a relatively successful outfitter’s business whose customers are mainly South African-born people. They include casual drop-ins and people wanting special outfits for wedding parties.

While many immigrants prefer to stay out of the politics of their host countries and focus mainly on the struggle of making a living, Owah has taken a different route. He has been an active member of the John Nkadimeng branch of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) since being introduced to the organisation by a friend. He is currently the only Nigerian national in the branch.

Owah is among a legion of Nigerian nationals who, since the official end of apartheid and birth of democracy in 1994, have joined the migration of other African nationals, Europeans and Asians to the new promised land of opportunity. Almost all the men present at Paradise Outfitters are Nigerian-born people who have come down south in search of a better life. They are members of the Nigerian Orange Grove community and this daily informal gathering in his shop is a “sort of community bonding,” says Owah.

Before 1994, Orange Grove was predominantly home to a community of Italian immigrants (fondly known as “little Italy”) where black Africans only came during the day to work in its homes, gardens, stores and other businesses. But Orange Grove is now home to people from across the continent, as well as from South Africa’s provinces.

The man who runs a store next door to Owah’s business is Pakistani. The woman who sells takeaway food from cooler boxes on the pavement is Nigerian. The young men who greet Nigerian restaurant bar owner Anthony Emijeke in the street on a Friday night speak Zulu, the dominant South African indigenous language.

A spirit of brotherhood and community prevails among the different nationalities that live here. The same spirit is present among the Nigerians, who rely on mutual support for survival in an unforgiving city where many dreams have crumbled in its bustling, brawling streets. With the Orange Grove Nigerian Association, Owah coordinates social-care initiatives that include supporting bereaved compatriots and their families, repatriating the dead, resolving domestic disputes, helping the sick, and boosting morale and a spirit of brotherhood.

Organisations like Owah’s exist in different communities across Johannesburg and in other South African cities. For many Nigerians they are an important link to their roots, as well as a support base in a far away country.

In the Johannesburg CBD, some 5 km south-west of Orange Grove, another Nigerian, Justice Ikechwukwu Okwarogo, founded a similar association after arriving in the country in February 2009. A native of Igbo State, Okwarogo runs a restaurant specialising in Nigerian cuisine near a busy taxi rank in Troye Street. He also runs an NGO, which focuses on environmental awareness issues, mainly in the CBD.

In Nigeria, he ran a computer repair and IT business but the operating costs – made worse by the country’s erratic electricity supply – were prohibitive. The restaurant business has done well, allowing him to finish his house back home in Nigeria. He employs South African cooks, who he trains in the Nigerian cuisine enjoyed by an endless stream of commuters passing to and from the nearby taxi rank.

Nigeria and South Africa have a strong, yet troubled bond, which stretches back to the apartheid days when the west African nation emerged as a leading continental voice against the apartheid regime. Diplomatic relations between Pretoria and Lagos began in 1994 with the opening of High Commissions in both cities. Formal diplomatic relations are conducted through a Bi-National Commission (BNC), established in 1999, which is jointly chaired by South Africa’s deputy president and the vice president of Nigeria.

Yet this has not prevented a somewhat destructive rivalry from developing between the two countries as they vie for dominance as the continent’s political, economic and sporting powerhouse. And on the ground in South Africa’s cities, this has seen Nigerian nationals targeted in violent attacks by locals, who accuse them of involvement in crime.

In January, in the latest of many flare-ups, mobs of angry South Africans in Rustenburg burnt down properties they claimed were being used by Nigerian drug lords and pimps. Unsurprisingly, many Nigerian immigrants prefer to stay in areas where they are less likely to be confronted by locals.

Definitive figures for the number of Nigerians living in South Africa are unavailable. A figure of close to a million has been bandied about in some quarters, but official figures tell a different story. In 2011, Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) put the figure at 26,341 after the census that year. In a 2016 community survey Stats SA put the number at 30,314. Robinson Sathekge from Johannesburg’s Migration Unit said between 3,000 and 10,000 migrants arrived in the city every month. “There are no statistics specifically for Nigerians,” he said. “However, foreign-national demographics indicate that Zimbabweans and Mozambiquans are the largest groups, followed by Nigerians, Chinese and Malawians.”

Owah’s journey to South Africa is emblematic of the daily struggle many immigrants face to build normal lives in somewhat abnormal conditions. Looking back on those early days, shortly after his arrival, he recalls living in a rundown hotel building in Johannesburg’s notorious flatland suburb of Hillbrow. Unlike many who find themselves stranded and destitute on the streets, he found a job at a clothing store owned by Malian nationals at the Carlton Centre, in the Johannesburg CBD. A year later he started his own business in Orange Grove.

Although life is much better in Johannesburg, it is not without challenges, which Owah blames on greedy landlords and housing agents, who, he says, charge ridiculously high rents. Some of his countrymen do dabble in unlawful activities to make a living, he admits, but says many of them do not set out to be criminals. Rather, many find themselves “in an awkward situation” and end up taking part in criminal activities. The authorities could ameliorate tensions between locals and Nigerian communities by taking a non-partisan attitude to crime, he suggests. “It’s very easy and straight to the point. If a Nigerian commits a crime, it must also be dealt with as crime, and not a “Nigerian crime”, argues Owah.

Okwarogo says the constant threat of being attacked by local mobs means many of his countrymen live in fear and unable to make long-term plans, given that they could be displaced at any moment. Therefore, many prefer to live in or very close to the cities that are populated largely by international and local migrants. The cosmopolitan environment makes it much easier to integrate, he suggests. “You prefer to stay in town, where you feel you are not alone. Johannesburg is for everyone.”

Not far from Owah’s shop in Orange Grove, a pumping, brawling nightclub and pub called the Princess caters to South Africans, Zimbabweans, Nigerians and people of many other nationalities, who come here to drink away the city’s blues under dim lights and jive to music pumping from the roaring hi-fi system.

The owner of the Princess, Tony Ejikeme, is also a Nigerian national, who started out selling food in the streets of Hillbrow. An elder of the Orange Grove community, he says that the association offers a sense of companionship, but it also provides some social cohesion and control. Members who do not adhere to the norms of the community are expelled.

He has lived in Orange Grove for 21 years and the suburb has become as familiar to him as his village back home. During this time, Ejikeme has seen attitudes towards foreign nationals in the area, especially Nigerians, gradually change. “Business in South Africa is very good, so as long as you know what you need,” he says. He moved to Orange Grove in 1997, and reckons he was the first Nigerian national in the formerly white suburb, which is now predominantly black.

“It wasn’t easy for us foreigners back then,” he recalls. South Africans, he says, tended to resent foreign nationals, who they felt were in the country to “steal” the hard-earned spoils of freedom. But, he adds, this attitude was partly a response to seeing Nigerian nationals engaging in criminal activity.

Ejikeme is also now a citizen with a South African identity document. His children speak English and their mother’s language, Zulu. Because of the neighbourhood’s cosmopolitan flavour they have a diverse range of friends of different nationalities. “Now we have Congolese, Zimbabweans and other nations. Cooperation in this area has improved from back in those days,” he says.

At his church, the Overcomers Christian Mission, which is also based in the CBD, Okwarogo counts Cameroonians, Congolese, Zimbabweans, South Africans and a diverse group of other African nationals as fellow congregants. “The house of God is made for all,” he says.

Owah’s view is perhaps more earth-bound. Nigerians in South Africa need each other’s support for survival. “What keeps us together is the love we have built among us as a community,” he says.

Lucas Ledwaba is the founder and editor of Mukurukuru Media, an agency specialising in feature articles and photographs. He is the author of Broke and Broken, The Shameful Legacy of Gold Mining in South Africa (2016) and co-author of We Are Going to Kill Each Other Today – The Marikana Story (2013). His work has appeared in the Mail & Guardian, the Sunday Times, City Press, Destiny magazine, Drum magazine and the African Times, among others. He has won several prestigious prizes for his feature writing, and his photographic work has been exhibited locally and in the USA.