Gorée Island: memorial to slavery

Visitors to Senegal’s notorious Gorée island learn about a 400-year old

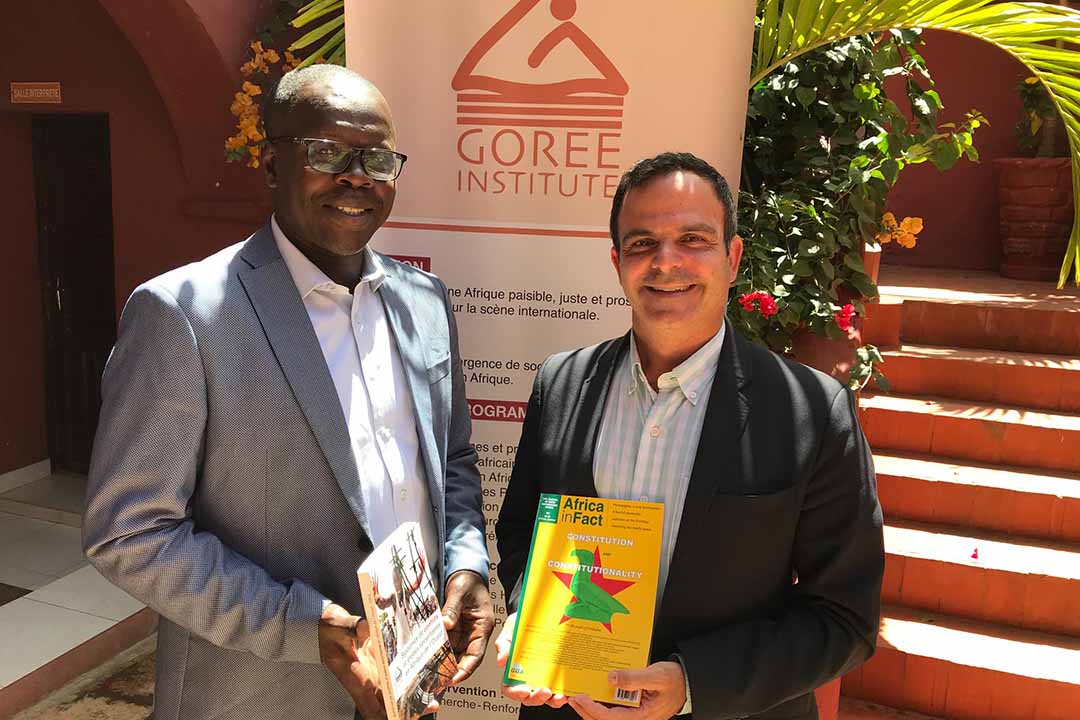

Doudou Dia, Managing Director, Gorée Island Institute and Professor Alain Tschudin, Executive Director of GGA. Photo: SUPPLIED

Slavery in Africa was one of the worst violations of human rights in history, extending over an entire continent and spanning 400 years. Its purpose was to make people objects of commerce and tools of work, stripping them of their dignity, even their humanity. The slave house on Senegal’s Gorée Island, with its dungeons and gigantic chains – where men, women and children were kept in captivity while waiting to be embarked onto ships for a voyage without return – is a forbidding symbol of that practice. The House of Slaves and its Door of No Return loom over the ocean to testify to these horrors. They also serve to preserve in our consciousness the amnesic effect of the temptations of power, wealth and artifices – values still embedded in the world today – which still lead man to instrumentalise his neighbour.

Some would claim that the number of slaves deported was no more than a few hundred or even a few dozen, while claiming that the House of Slaves was little more than a transitory prison. We do not subscribe to such attempts to deconstruct Gorée as a myth. This would be to deceive the millions of people who have visited the island so far. As a matter of fact, Gorée was a hub of the slave trade in West Africa. For the purposes of this article, the island was the “main and most important transit centre of the … Negroes to the French colonies of America”, according to Pape Chérif Bassene in his paper, History and memory of Gorée in the Atlantic Treaty, paramnesia of localisation, Africa and development, published in 2014 by the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa. The name is possibly a corruption of the Dutch Goedereede, meaning “good roadstead”; later it became Gorée in French, meaning “good harbour”.

Sitting not far off Dakar harbour, Gorée offered excellent anchorage for large vessels, as well as facilities for water and wood. As with Moragador port on the Gold Coast, Gorée could shelter as many as a hundred vessels waiting to benefit from the above-mentioned services and take advantage of the geographical position of the island. Babacar Joseph Ndiaye, the first curator of the House of Slaves, spoke of “millions” of captives crammed into ship holds from the island as they set off on the “journey without return”. Ndiaye’s main aim was to commemorate this function of the island, say Hamady Bocoum and Ibrahima Thioub of the Cheikh Ana Diop University. From an epistemological point of view, he “never claimed to obey university rules of knowledge production”. As Eloi Copy, his successor, says: “Gorée synthesises the memory of the slave trade, even if revisionists quarrel about numbers.

Academics and scientists share the same perspective.” According to Bassene, Ndiaye tried to “quantify the suffering symbolically”. According to French painter Georges Braque, our time prefers scientific and legal truths. However, he went on to say that “there are other truths of another order and we tend to neglect them, sometimes even to deny them to the point of cutting ourselves off from the deep dimension of our human existence…” Gorée is a vital reminder of these other truths. It is a memorial space that has become a place of restitution of the identities lost in the diaspora. As such, it also represents a convergence of many peoples and cultures. The concept of a “Door of Return” is a reimagining of the history of the island and its contemporary role to accommodate the double vocation of remembrance and resilience. Beyond its memory function, Gorée is also a space for promotion and education in human rights.

Indeed, a visit to the island – and especially the guided tour of the House of Slaves – is a way to rewrite the history of slavery by reconciling the black person of the Diaspora with himself or herself and with their African brothers and sisters. A version of history presents these people as the privileged accomplices of Europeans during the slave trade. But this is a discourse of deconstruction and a contextualisation of power relations that casts accomplices as victims in the same way as their captives. A visit to Gorée inspires many African- American visitors, in particular, to return home to take a DNA test to establish their identity, says Laity Bodian, a tour guide. Often they trace their origins to Ghana or Senegal. “They’ve always been made to believe they have no history,” he says, “but after finding their roots they often plan a second visit.” Abdoulaye Ndiaye, also known as “Colonel”, another tourist guide native to Gorée, agrees. “After visiting Gorée, some people feel that they must return to the land of their ancestors, as they now see it,” he says.

Tourists from the United States, the Caribbean and other places come looking for this sense of belonging, often organised in groups and despite financial difficulties and lack of time. “For many, the trip to Gorée is a pilgrimage,” he says. “Some return with the ashes of their ancestors to pour them into the sea at the island. These views reflect something of the impact of the island. Through its cathartic function, through its restoration of identities and its contribution to cultural exchange, the island is becoming a symbol also of mutual understanding and tolerance between people. The Gorée Diaspora Festival, organised by the municipality, is part of this endeavour to “allow members of the diaspora to find the identities they lost on the island,” says Ndiaye. Gorée’s planned opening of the “Door of the Return” will help to make the island a crossroads of intercultural dialogue.

Seminars and conferences are organised for this purpose. The international festival was initiated in a global context of intolerance and identity crises, he adds. As such, it is part of a process of “proactive memory”, that goes beyond the image of a door that opens on a “journey without return” by opening it the other way, that of the “Return to Gorée”. The Dakar-Gorée Jazz Festival is another event that is helping to open the island up to the peoples of the world – even if the quality of the organisation of these major events remains to be improved in the eyes of some. The islanders also hope to benefit from the tourist trade – among them prominent women traders in African art and clothing, even though some say their dynamism and commercial aggressiveness are harmful to the image of the island and its efforts to promote tourism. But this a priori perception tends to overshadow the dimension of human relations that these women manage to weave with visitors.

In particular, if they happen to speak the visitors’ language, they like to make them aware of other realities of daily life on the island beyond the rehearsed speeches of tour guides. “Colonel” insists that his relationship with tourists is more than merely commercial. The main aim, he says, “before thinking about business”, is to try to connect humanity with its history. Though large numbers of people visit every year, the local population does not really live from tourism either. Many rely on family links around the world to provide opportunities. The island’s people, particularly the young, are globally mobile and do not have to risk the “suicidal routes” that many do to reach developed countries. Thioro Gueye, a native of the island and a retired restaurateur who has long been engaged in the public life of the island, argues that the opening of the House of Slaves as a tourist destination is also opening up new opportunities for islanders, especially through the visits of African-Americans.

She cites the example of the partnership between the island and the US state of Louisiana in 2003, which saw a delegation of Goreans organising a conference on slavery and an exhibition of African art objects there. This led to the creation in Louisiana of an African museum exhibiting objects mainly from Gorée. Moreover, some French people participated in the construction of two additional classes for a crowded elementary school, she adds. These examples amply demonstrate how the proposed “Door of the Return” will create opportunities to bring people together, as well as for the socioeconomic development of the island, where the living conditions of some inhabitants could do with improvement. Respect for human rights must be anchored in the consciousness of human beings to be effective and sustainable, said Gueye. Keeping memories alive of one of the most sordid violations of human dignity in history is one way to achieve this.

Beyond its tourist attractions, Gorée Island serves this purpose. As Eloi Coly, the curator of the House of Slaves, reminds us, these sites call for an awareness of all forms of human rights violations and their harmful consequences for the human condition. The need for education and awareness raising on these issues is all the more urgent because such practices still exist throughout the world. A plaque at Gorée’s Historical Museum testifies to this: “the struggles for power and wealth that existed hundreds of years ago still exist in the world”, it says. In 2017, global estimates of modern slavery indicated that more than 40 million people were currently victims of modern forms of slavery: forced labour (including child labour), human trafficking, and sexual exploitation. Of these, 71% were women and girls. Moreover, a vast network of human trafficking was discovered on the Libyan coast in 2018-2019. Candidates for illegal immigration were the main victims.

These shocking figures make clear the educational significance of a visit to the House of Slaves. The museum attracts many school visits as part of extramural educational programmes, while the topic of slavery is included in the curricula of Senegal’s high schools. During the school year, the site receives up to 1,500 students per day from all parts of Senegal, accompanied by their teachers, says Coly. A major project to rehabilitate the House of Slaves and construct an international centre for the interpretation and documentation of the slave trade is now under way. The “Door of the Return” will open to a memorial area that synthesises the history of the slave trade, and acts as a place of convergence for all people and cultures. Above all, there is a need to re-arm consciences around the world in their fight against all forms of human rights violations.

Moustapha Gueye is a research associate with the Gorée Institute, Senegal. He holds a doctorate in information and communication sciences and is a researcher and senior lecturer at the Centre d’études des Sciences et Techniques de l’information (CESTI) at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar. His research interests include media, conflict, peace and democracy.