Africa: the written word

Africa’s great libraries are stories of state formation and empires, and of people who thirsted for knowledge

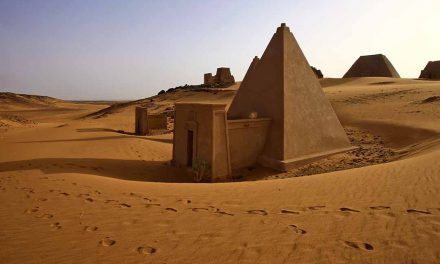

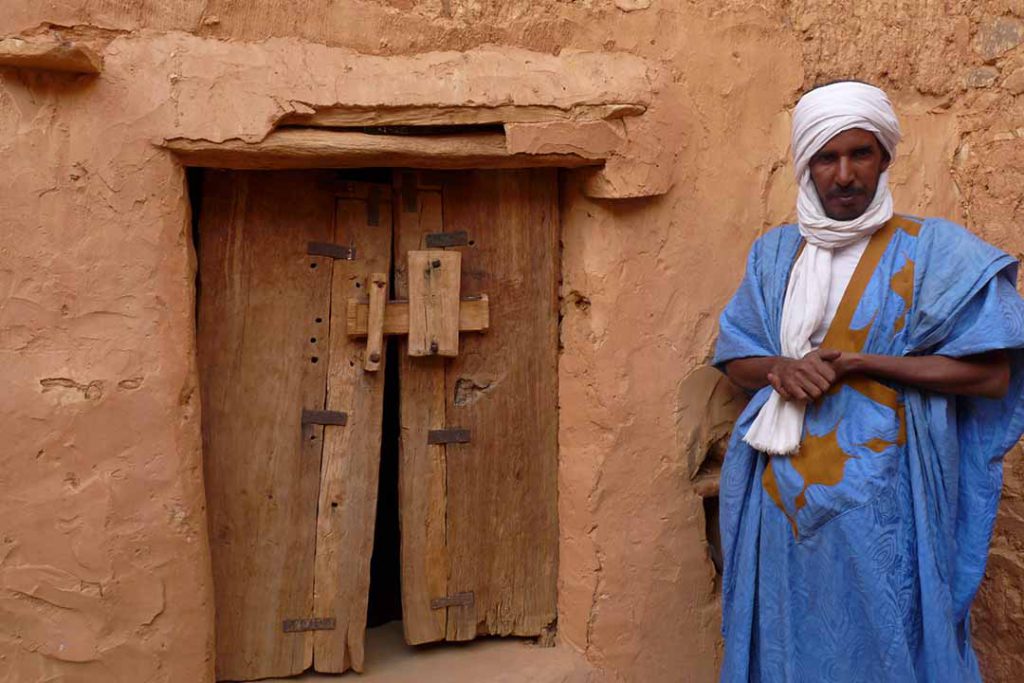

The Hamoni library in Chinguetti, Mauritania. Photo: WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

Reading and writing are miraculous activities; they transform the human condition, making possible new modes of social life. In a world which is slowly approaching total literacy, it can be difficult to recall that reading and writing were once rare skills. Writing developed independently in several prehistoric places, helping to transform them into historic sites. From the first inscription on a cave wall to the development of the library lies a journey of untold inventions and their dissemination. A range of factors were necessary for libraries to develop, as Lionel Casson argues in his book Libraries in the Ancient World (2002). Schools were needed to spread the knowledge of reading and writing. The number of readers had to grow, and their skills had to be more than basic to create a literate class. The writing of books needed readers who read books for other than utilitarian reasons.

And the demand for books had to grow enough to foster a book trade. “Once books were commercially available, the literary-minded were able to build up collections,” writes Cassson. “And the private collection was the precursor of the public library.” Africa has often been regarded as a continent with few connections with the wider world. European thinkers as different in time and place as German philosopher GWF Hegel and British historian Hugh Trevor- Roper dismissed the continent as out of the mainstream of human existence. Certainly, Africa has had to cram the attainment of literacy into a much shorter historical timeframe than most other regions in the world, starting during the colonial period. In 1990 the adult literacy rate was 53%, while in 2015 it was estimated to be 63%, according to the Africa Library Project. Its overall literacy rate is 59%, as compared to 99% in the US, the website says, quoting recent UNESCO figures. Yet, as so often, even a little research can reveal a much more nuanced picture than the standard one.

It is a little-recognised fact, for instance, that, historically, Africa has served as host to three great libraries, each representing one of the world traditions. The first was possibly the most famous library in the world, the library at Alexandria, which represented the Hellenistic tradition. The most magnificent city of its era, Alexandria was built in 323 BC at the behest of Alexander, the Macedonian conqueror. Alexander “hoped that the genius of Hellenism” would be perpetuated in the “metropolis of culture to benefit the entire world”, according to Theodore Vrettos, writing in Alexandria, City of the Western Mind (2010). Its library itself was built a generation later, possibly by Ptolemy Soter, a general of Alexander’s who declared himself king in 304BC. Ptolemy, who was himself a historian, reportedly engaged Demetrius of Phaleron, a Greek politician and philosopher of the Aristotelian school, to found a research institution with its own library.

A second century BC letter asserts that he was asked to collect “all the books in the world”, according to the online Encyclopaedia Britannica, and it is thought that he was given a large budget to do so. He acquired 600,000 manuscripts – each a long roll of papyrus. The grammarian Athenaus claimed that the entire library of Aristotle, inherited by his pupil Theophrastus, which included the master’s works (all 445,270 lines, according to Diogenes Laertius) was sold to Ptolemy II and housed in the library. Such was the determination of the founders to make it a universal library that ships in the harbour were searched for books. The works acquired were not only Greek and Roman. “Oriental writings were translated into Greek and placed in the library; as were ancient Egyptian texts, the Hebrew scriptures, and writings ascribed to the Persian prophet Zoroaster,” according to Vrettos.

More than a library, the institution was the prototype of the modern university or research centre, with columned walkways, a communal dining room, lecture halls and the library itself. The museum, which Casson says was a kind of think-tank, attracted some of the best scholars of the time, who were provided with large tax-free salaries. Among the scholars who worked there were Euclid, the great mathematician, Strato the physicist, Archimedes (famous for shouting “Eureka” after solving a problem of hydrostatics, a discipline he invented), and Aristarchus, who posited a heliocentric theory of the planetary system 1,800 years before Copernicus. Various stories are told about its famous destruction, including that it was burned by Julius Caesar, but an offshoot may have survived until Christian zealots destroyed it in the fourth century AD. The second great library to exist on the African continent is housed at the Monastery of St Catherine’s in Sinai, Egypt.

Its official name is the Sacred Monastery of the God- Trodden Mount Sinai, and it is built at the foot of the mountain where Christian tradition says Moses received the 10 commandments from God. Still surrounded by fortress walls constructed on the order of the Roman emperor Justinian, it is said to be one of the oldest functioning monasteries and includes what is possibly the oldest continuously functioning library in the world. In 623 AD, the monastery received a “letter of protection” from the prophet Mohammed, according to the monastery’s own website. Known as the Ahtiname, the document is an important factor in the monastery’s survival, as it ensured “peaceful and cooperative relations between Christians and Moslems,” the monastery says. The library is distinctive as “the oldest and most important Christian monastic library collection” in the world, according to its website.

It includes some 3,300 manuscripts, two thirds of them in Greek and the rest mainly in Arabic, Syriac, Georgian, and Slavonic, with a few in Polish, Hebrew, Ethiopian, Armenian, Latin, and Persian. “Most of the manuscripts are Christian texts for use in the services, or to inspire and guide the monks in their dedication. But others are of an educational nature, such as classical Greek texts, lexicons, medical texts, and travel accounts.” The library’s most important manuscripts are the fourth century Codex Sinaiticus, one of the oldest surviving complete bibles, and the Codex Syriacus, a palimpsest, “one of only two manuscripts in the world that preserve the text of the Old Syriac translation of the gospels”. The third African library representing a great tradition is actually a collection of libraries: those of Timbuktu, a trading junction at the bend of the Niger river.

Again, an empire was involved, this time that of Mali under Musa I, who is reckoned to have been the richest man ever to have lived. When Musa I arrived at Timbuktu in 1325 on his way back from Haj in Mecca, it was already an established centre of Islamic learning with three madrassahs (schools): Jungaray Ber, Sidi Yahya, and one based at the famous Sankoré mosque, built in 989. Musa I fell in love with the city, and decided to deposit his huge library there. He instructed Andalusian architect Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, who had returned with him from Arabia, to construct the Djingereyber mosque, now an architectural masterpiece. It became the most important African archive since the library of Alexandria. Timbuktu flourished during the reign of Askia Muhammed from 1494 to 1529, after it was captured by the Songhai in 1468. The centre of Islamic studies at the Sankoré mosque housed the Ta’rikh-al-Sudan, a history of the Sudan and the Songhay empire written by religious scholar Abd al-Rahman al-Sa‘di in the 1600s.

More than 60 archives were kept at Timbuktu, “an intellectually voracious and innovative state which drew in the most cutting-edge thinking from all over the region and beyond”, according to Gus Casely-Hayford, writing in Timbuktu (2018). “Where his Ghana empire forefathers had invested in systems of oral history, in griots and storytellers, Mansa Musa had fundamentally shifted the culture of record,” writes Casely-Hayford of Musa I, the empire’s ruler. “In consciously supporting writing the history down, he had created a distinction between himself, the emperor’s court, and the law.” As philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne points out, Timbuktu shows that the identification of Africa with orality is inaccurate. At the height of its fame, Timbuktu could accommodate 25,000 students, and housed at least 400,000 and perhaps as many as 800,000 manuscripts, Casely- Hayford says (though this figure is disputed).

Moreover, as in Alexandria, a flourishing trade in manuscripts emerged, with book sellers, publishers, writers and calligraphers ministering to private book collectors. More recently, there have been initiatives to house the city’s texts in more modern facilities. Casson says that the archives contain texts about Greco-Roman astronomy, Platonic discourses with commentaries by Muslim scholars, as well as texts on medical issues, slavery and the ethics of government and doing business. Most were written in Arabic, but some were in Songhay, Tamashek and Bambara, and even one in Hebrew. Africa has seen other more or less successful attempts at scholarship and the gathering of texts. One intriguing example is at Aksum, sometimes spelt Axum, in what is now Ethiopia, where the Bible was reportedly translated into Ge’ez, a language widely spoken in East Africa.

More tangible evidence of literate activity has been found in the city of Chinguetti in Mauritania, where five libraries containing some 1,300 Quranic manuscripts, some from the 10th century, survive to this day. But for various reasons, these have not been tapped by the global academic community. The texts are housed in family collections. “The oldest tome, written on Chinese paper, dates from the 11th century,” according to 2010 article in The Guardian newspaper. A Roman library at Timgad, or Thamugadi, in what is now Algeria, was founded by Trajan around 100 AD. Another was found in Carthage. According to Casson: “When we turn to the western half of the Roman empire, a curious picture emerges. Throughout what is today England, Spain, France, and the northern coast of Africa, we have proof of the existence of libraries in but two places, Carthage in Tunisia and Timgad in Algeria.”

That is, in Africa. The stories of these libraries are in their way epic. They are bound up with the rise and fall of empires. And they express the aspirations of people who were not content with the immediate, who thirsted for knowledge of their social and political worlds – and also of the stars, the universe, of divinities, of ethics and philosophy.