The ANC and previous regimes have all seen rural areas as more deserving of attention and resources than cities, making it nearly impossible to talk seriously about urban policy

Since the end of apartheid a central issue of democratic governance should have been to rethink the political economy of cities. However, continuities from past to present remain deeply embedded in the South African social fabric.

Despite policy-making attempts from 1994 to the present day, the national government has been unable or unwilling to free itself from the shackles of thinking short term with regard to the country’s cities. The work of developing a vision of, and practical steps towards, building post-apartheid cities has been left to local government, academics and consultants, with occasional spurts of interest from national government.

After many years of trying to put in place an urban policy, in 2016 South Africa finally came up with the cabinet-approved Integrated Urban Development Framework (IUDF). Given the long delay, it is perhaps unsurprising to find that South African cities face extremely high levels of community-based protest action against government for service delivery failures. At their height in 2015/16, the country saw more than 30 such actions per day, a near-constant feature of the landscape. Attempts to develop urban policies in South Africa have largely failed so far. The question is why.

A 2016 UN-Habitat study has made some rather strong claims about the IUDF: “Brazil, China and South Africa are examples where clear national urban policies have been vital in orientating action to tackle inequality and to energise the development process”. But this optimism is overstated. The Framework, as with so many initiatives, is in some danger of being subsumed into government’s existing planning, funding and other cycles, all of which operate in five-year time periods. These cycles are singularly ill suited to meet the core urban challenges in South Africa, which need long-term solutions.

The issue is not merely the administrative need to manage all processes to ensure that they are fully contained by existing bureaucratic systems and subservient to the political agenda of the elected government. Rather, the notion of “the urban” is itself contested in South Africa. “The urban” is less important, politically, than the rural. Cities are politically dangerous, representing pluralism, choice and lack of control.

Globally, cities are inherently threatening to political parties that have yet to come to grips with their pluralism, and which retain a commitment to rural areas and traditionalism. The current leadership of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) thinks “rural” and mistrusts – and misunderstands – “the urban”. This contributed to the ANC losing control of the major metropolitan cities of Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Municipality in the 2016 local elections. Cape Town had been lost some years previously.

One reason for the party’s rural preference is that urban areas lack the ease of control offered by traditional leaders in rural areas. During most of the 20th century, segregationist and later apartheid regimes sought to deny Africans any urban residential rights, corralling them in rural reserves under the control of chiefs. At the same time, by shrinking the land available to Africans, they forced them to migrate to urban areas to sell their labour. However, most Africans were present in urban areas on a temporary basis, and were also forced to return to the rural areas that had been designated as their “homelands”.

The same struggle continues. This time, the challenge is to make rural areas sufficiently attractive to keep people there. The ANC vision was perhaps exemplified by a major intervention under former president Thabo Mbeki, the Integrated Rural Development Strategy (ISRDS), which aimed to “attain socially cohesive and stable rural communities with viable institutions, sustainable economies and universal access to social amenities, able to attract and retain skilled and knowledgeable people, who are equipped to contribute to growth and development”.

In its own words, the strategy presented “an opportunity for South Africa’s rural people to realise their own potential and contribute more fully to their country’s future”. But since the end of apartheid, citizens of rural areas have consistently voted with their feet, heading for urban areas and away from the desperately poor rural areas where livelihoods could not be maintained and no industrial, mining or other job opportunities exist.

In post-apartheid South Africa, the democratic government has sought to maintain and extend rural controls. From the 1950s, local power and control over land rested with the “Bantu authorities”, and with the traditional chiefs in the system. Yet, “government policy seems to be increasingly entrenching this – even potentially extending it … they have presided over what is largely an economic stasis in the former homeland areas,” says historian William Beinart. The role of chiefs in the socio-economic decline of rural areas may be open to some debate, he adds, but they clearly bear considerable responsibility. And in recent years the ANC has sought to ramp up their powers.

The Traditional Courts Bill, which was introduced in 2008, revised and reintroduced in 2012 and again in 2017, aimed to give tribal chiefs more power than they had under apartheid. This despite a range of contradictions with other aspects of the ruling party’s declared policies, such as gender inequality. An early version would have given chiefs powers to punish, tax, enforce unpaid labour and allocate land. In another version introduced by the ruling party, the decisions of chiefs would have had the same status as those of magistrates’ court rulings. Many of these proposals were watered down in 2012 and again in the 2017 iteration because of the level of hostility from rural communities. But the intent is of interest here.

The 2008 and 2012 iterations were drafted after only consulting traditional leaders through the House of Traditional Leaders. The ruling party has long regarded the traditional leaders “as a secure voters’ base”, according to a January 2017 article in The Daily Maverick by Marianne Merten. “This effectively politicises the often unequal power relations in rural areas by putting traditional leaders, not communities, on (sic) centre stage,” she argued. In 2015 National General Council documents, the ANC describes traditional leaders as playing a key role “in representing and preserving the culture of community members” and as a key driver of development in rural areas.

Rural areas have been a central focus of the ANC since 1994, as they were for previous regimes. Rural areas have been seen in a different light, as more deserving of attention and resources than cities. As a result, it has been nearly impossible to talk seriously about urban policy. Since 1994, development policies, programmes, plans, funding vehicles and so on, have prioritised the rural over the urban. Among other reasons, this is because the question of land ownership has been a central feature of ANC politics and policies, with a deeply felt need for restorative measures for all South Africans removed from or denied access to land.

The rural focus takes various forms. There is an entirely legitimate concern with the return of the land – given that the 1913 Natives Land Act gave whites 87% of the land, leaving 10% of land for black South Africans (this was later increased to 13%). It also forbade the selling of “native land”, and disallowed sharecropping and tenant farming. As the historian Charles van Onselen put it in a 1996 study, “between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, the emerging South African state engaged in a hundred-year war to seal off the sharecropping frontier so as to deliver to politically privileged white landlords a black labour force that capitalist agriculture demanded.”

The land left for “natives” in “native reserve” areas was communal and under the control of African chiefs, some of who were genuine, while others were created by the state. The Land Act strengthened the position of the chiefs by making them part of the state administration.

Most of the 20th century in South Africa comprised an ongoing attempt to maintain control of rural areas and to ensure that a reserve army of labour was locked up in rural areas, but forced to migrate for work to urban areas – where black peoples’ right of residence was strictly limited and policed. This was begun under colonialism and segregation, and reached its apogee under apartheid, where the infamous pass laws required blacks to carry “urban passports” (the “dompas”) permitting them to be in an urban area.

Later, mythical “homelands” were created in the least hospitable and least arable parts of South Africa, whence the majority of black South Africans were forcibly removed. In the process, they were turned from South African citizens into citizens of homelands that accepted “independence”. In all this, the chiefs played a key role.

The irony is clear. Strengthening chiefs in the post-apartheid context offered opportunities for social control that urban areas simply do not offer. This is precisely what the ANC would try to replicate a century after the introduction of the Land Act, signalling the less laudable aspect of the rural focus: control.

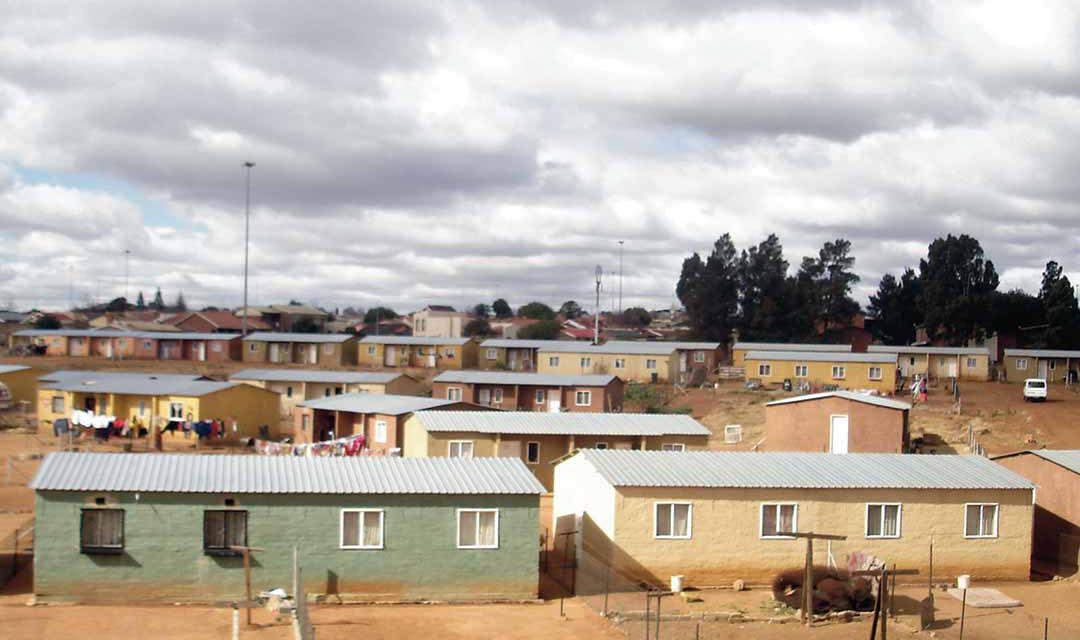

The spatial challenges inherited from apartheid – which ensured that black urban dwellings were physically distant from “white” areas, and used natural (rivers or streams) or man-made (motorways, industrial plant) barriers to hardwire the physical separation into the landscape – have been compounded in post-apartheid South Africa by the need to urgently deliver housing stock to the black population denied under apartheid. This has been paired with the (non) availability of affordable land after a negotiated end to apartheid enshrined the retention of private property.

The result has been the construction of new mass-housing stock on land far from economic hubs in cities (in effect, these houses were versions of the classic township “matchbox” houses, with few social or economic facilities). Such developments did not deliberately insert buffer zones as had occurred under apartheid, but in every other respect the new housing stock closely resembled township development under apartheid.

The spatial disfiguring of the urban landscape, coupled with the size of the urban population, suggests that South Africa’s cities should also have received close policy attention after 1994. But they did not. Since it took power in 1994, the rural has dominated the ANC’s political imaginary. It is in this context that urban policy in South Africa has to be assessed. The ruling party’s approach to South Africa’s cities is intrinsically bound up with politics.

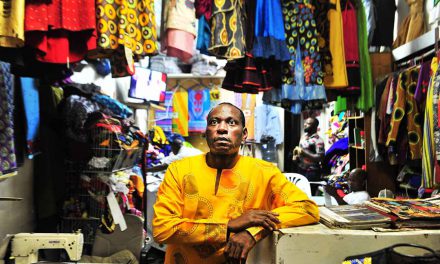

Finally, the very idea of cities and everything they represent has come under sustained criticism from a traditionalist standpoint. The “real” African, in the South Africa of former President Jacob Zuma – himself a rural traditionalist – lives on his (the pronoun is deliberate) land and defers to his traditional leader. Doing so enables him to be in touch with his ancestors and traditions, and to abide by his customs.

Cities are inherently at odds with this worldview. They are spaces of multiplicity and choice, of pluralism in politics, lifestyle and behaviour. Cities are, in effect, home to what Zuma has termed “clever blacks”. It is perhaps no coincidence that he made this remark while defending the Traditional Courts Bill, in 2015. He said that some blacks “who become too clever” had “become the most eloquent in criticising themselves about their own traditions”. “Whose traditions will they (the children) practise? The Zuma traditions or the Smith traditions? We have lost direction. Even if I live in the highest building, I am still an African.”

It is in this context that the IUDF is struggling to gain purchase. The IUDF is an important document, not least in finally managing to get approval for urban transformation at the highest levels of government. However, its prospects need sober assessment. The Framework is clear that early moves are needed. These include identifying long-term spatial transformation triggers, identifying state-owned land near city centres, and placing spatial transformation squarely at the centre of the national urban debate. It is equally clear that 50- to 80-year investments are required, to transform the disfigured landscape. This takes political courage alien to a risk-averse administration.

Meanwhile, the national government focuses on “reversing the legacy of the 1913 Natives Land Act”. “Land” (of all types) has featured in 5,356 committee meetings in Parliament, 415 in 2017 alone. Rural issues were discussed on 582 occasions in parliamentary committees in 2017, compared with just 180 for urban issues, according to a 2017 report by the Parliamentary Monitoring Group.

In addition, the Framework has run into the reality of how government operates. After international review and cabinet approval, the IUDF needed to generate an implementation plan and attract resources that would enable it to become a reality. An implementation plan has now been prepared, but the team involved was not the same one that drafted the Framework, as I learned from a personal communication from the IUDF chair. This is not automatically problematic, but it might be in this case.

By the time the implementation plan appeared in 2016, the IUDF had been firmly put in its place. The plan noted the need to stick to long-term goals, but immediately located all IUDF actions within the existing machinery and time frames of government. These include the Integrated Development Plans of cities and provinces, the Medium Term Strategic Framework of government (which ensures all plans are in line with ruling party priorities), the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (which allocates budget over a three-year window), as well as spatial development frameworks, budget delivery plans, and the rest. All operate within, at most, five-year cycles.

It is inevitable that government programmes must follow appropriate procedures and fit in with the existing machinery of government. However, when that machinery has failed to come to grips with urban challenges, or where government already faces considerable challenges in its ability to co-ordinate activities on the local/provincial/national levels, as well as in integrating planning, budgeting and delivery, it is fair to repeat the caution we noted at the outset, in response to UN Habitat’s very positive welcome to the IUDF.

South Africa has a national urban framework, and a good one. However, it is questionable whether it can realise its long-term, multi-sector and multi-sphere government goals. In particular, its implementation plan seems to have squeezed its recommendations into existing mechanisms, structures and programmes without taking account of their complexity. South Africa’s cities will likely face their future on their own.

Professor David Everatt is Head of School, Wits School of Governance. He is the former executive director of CASE, a founding partner of Strategy & Tactics (winner of two Impumulelo Black Empowerment awards), and founding director of the Gauteng City-Region Observatory. He was the chief evaluator of the South African Constitutional Assembly between 1995 and 1997, and has researched issues from poverty and inequality to urbanism to class formation and voting behaviour. He was vice-president (sub-Saharan Africa) for the “Sociology of Youth” committee of the International Sociological Association for 14 years, and now sits on their advisory board, and serves on the board of the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation.