List of countries by income equality. Wikimedia Commons

It may be impossible to replicate Asia’s middle-class miracle in Africa given the disparities in governance, growth, and income inequality between the continents

It has often been suggested that Africa should emulate the achievements of the high-performing East Asian economies, which have seen explosive economic growth and the emergence of large middle classes since the end of the Second World War. But others argue that even Africa’s high-performing economies cannot usefully be compared to the high-performing Asian tigers because they still have small manufacturing sectors, undiversified economies and disparities in economic distribution across households and individuals¬ ¬– and still, despite high levels of growth in some countries, small middle classes.

The economies of East Asia are regarded as having developed on a high growth, low inequality model between 1960 and 1990. Seven of them – Japan, South Korea, China, Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia and Hong Kong – are regarded as high-performing. Robert Fogel, an American economic historian, argued that four factors define high-performing Asian economies: “the trend toward rising labour force participation rates, the shift from low to high productivity sectors, continued increases in the educational level of the labour force, and other improvements in the quality of output”. In particular, all the Asian economies are distinguished by their large investment in human capital. This meant that by 2010 or so, Asia’s middle class had expanded to 525 million people, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Could the East Asian miracle be paralleled in Africa? To answer this question we need to return to the idea of “middle class”. As shown further in this article, there are indications that it is the development of a sustainable middle class that drives and sustains development in a market economy. But defining what “middle class” means proves to be difficult. Unlike other socio-economic terms such as poverty and unemployment, there is no universal consensus or benchmark definition of this concept.

In a 2010 working paper written for the OECD, Homi Kharas, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, argues that perhaps the single most important determinant of class membership is the level of income available for consumption. Using this as a measure, the global middle class can be defined as “the difference between the number of people with expenditures below the $100 per day threshold and the number with expenditures below the $10 per day threshold”. On this basis, the global middle class consists of 1,8 billion people: North America (338 million), Europe (664 million) and Asia (525 million). The United States leads among individual countries, with some 230 million middle class people. The EU has almost 450 million middle class consumers, and Japan has a further 125 million. “There are very few middle class [people] in sub-Saharan Africa: about 32 million or roughly the same as Canada,” he wrote.

He adds that the global view masks differences in purchasing power in different countries. The African middle class, according to the Pew Research Centre, consists of those earning between $10 and $20 a day. The Asian and African Development Bank, and the African Development Bank (AfDB), offer a broader definition of the African middle class as people who spend between $2 and $20 per day, but divides the category into two: a “stable middle class” and an “unstable middle class”, with levels of income, wealth and consumption as determinants.

The AfDB offers three sub-categories. The first is a “floating class with per capita consumption levels of between $2 [and] $4 per day”; this group lives just above the poverty line and is vulnerable in times of economic decline. According to the AfDB, this is important because membership differentiates between poverty and a relative degree of spending power. The AfDB’s second sub-category is a “lower middle class with per capita consumption levels of $4 [to] $10 per day”; this group is able to buy basic essentials, such as food, shelter, clothing and medical care, but is not seen as stable. The third sub-category is an “upper middle class with per capita consumption levels of $10 [to] $20 per day”, and is seen as stable in that its members consistently access high-quality services such as private healthcare and education; they are not threatened with a sudden decline in their socio-economic status.

According to Standard Bank South Africa, which operates across the continent,

some 4,1 million Nigerian households – or just 11% of the total population – are now considered middle class based on the Living Standards Measure (LSM). South Africa’s middle class is described as comprising households of four persons with a total household income of between R5,600 and R40,000 per month after direct income tax. It is thought that this applies to some 13,7% of the population.

There is a wide disparity between the upper and the lower income middle classes in Africa. There are also are wide disparities in the distribution of wealth across the continent’s 55 countries. Many of these countries have not been able to escape economic, political and social challenges; the majority of their populations are still trapped in poverty when compared with other regions of the world, according to a 2015 study by Professor Louis Picard of Pittsburgh University’s international development division, and others. Africa’s large informal economies make it even harder to make reliable estimates. Yet observers remain positive that Africa is on the path from the developing stage to development. In 2011 the AfDB said that by 2060 the middle class in Africa would number some 1,1 billion people, about 42% of the population.

These definitions are all based on income, expenditure and consumption but other factors may be involved in defining the middle class. In Europe the middle class has traditionally been defined by academic qualifications, occupation and social role, because these factors are considered to influence economic opportunities and political views. William Easterly, a professor of economics at New York University, has argued that modern political economies stress a balance between political and economic development. This is why Africa’s middle class is not only important for economic growth but is also crucial for maturing democracies.

History tells us that countries that have been able to achieve this balance have developed a stable and growing middle class, while in many countries in developing regions such as Africa, the middle class has remained vulnerable – mainly because of political instability. Where there is economic growth even those with university degrees and stable employment have little political influence, and where they do, they often support populist parties and ideas further hindering effective economic management.

If we compare the development of the African and Asian middle classes and evaluate the African middle class in more detail, considerable differences become evident. The AfDB’s absolute measure for the term “middle class” is misleading because it ignores inequalities within a huge range of income groups and kinds of income. While growth rates similar to those of Asian countries are now being seen in parts of Africa, such as Kenya, and Ethiopia – the continent has yet to see a similar significant growth in its middle class. African countries’ growth experiences are extremely varied and episodic. Low levels of investment are an important factor in Africa’s slower growth, but its slower productivity growth more starkly distinguishes the continent’s growth performance from that of the rest of the world.

In a 2015 study, professors Biodun Olamosu and Andy Wynne observed that most African countries gained their independence from their former colonisers in 1960, but that the continent experienced low levels of economic growth up until the early 2000s. Though the continent had vast swathes of agrarian land, it also had a shortage of skilled labour, and capital. Many African economies became exporters of mineral resources and remained heavily dependent on primary production or the export of one or two products. The introduction of neoliberal policies, which emphasise free trade and opening markets to foreign competition – limiting the role of government in providing services and subsidies to the poor – further increased inequality on the continent, they suggest. As a result says the AfDB, Africa’s middle class presently numbers about 180 million people.

If we use the AfDB’s absolute measure – people who spend between $2 and $20 per day – the African middle class is on the rise. But clearly its progress has been nothing like that of its Asian counterpart. Major investors are withdrawing capital from Africa and investing it in other regions. In 2013 Cornel Krummenacher, chief executive officer of the Nestlé Equatorial African region, told the Financial Times that the company had decided to retrench its employees because “we thought this would be the next Asia”. The company had discovered that Africa’s middle class was “extremely small and … not growing”, he said.

In a 1994 study John Page, from the Brookings Institution, argued that Africa had failed to develop diversified economies that created employment opportunities for a sustainable middle class mainly because of dual economies, even in those countries with some level of industrial development. Only a few African countries have any sort of manufacturing base, and the majority of its countries – including the continent’s super powers, Nigeria and South Africa – still have large informal economies. In reality, most African people are either poor or rich.

So is it realistic to argue that the East Asian miracle could occur in Africa? Observers believe that only some of the continent’s countries are presently in a position to achieve such a transition. These include Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Uganda. In a 2016 study, Sandile Swana and Lumkile Mondi, from South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand, argue that the time frame matters. In their view, it takes 25 years to transform a nation from a developing stage to a developed one. They argue that Africa should emulate Asia’s “high and sustained economic growth” between 1965 and 1990.

Standard Bank South Africa says that economic growth has been instrumental in creating an emerging middle class in Africa but that the results are generally disappointing, with only

15 million households across 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa considered to be middle class (excluding South Africa). Between 2004 and 2012 South Africa’s middle class ($10 to $50 a day) grew from 5,3 million to 7,9 million, while the black middle class went from 1,7 million to 4,2 million, which is more than 50% of the total middle class population.

High economic growth rates are not solely responsible for generating a rising middle class. It has been argued that if Africa is to achieve high growth and low inequality, state intervention must create an environment that fosters economic growth and a subsequent, reduction in poverty. In 2001 Easterly said that empirical studies showed a correlation between better governance, low inequality, high growth, investment in human capital and poverty reduction. Page has argued that Ethiopia, one of the continent’s most populous nations and with one of its best performing economies, saw its middle class share of wealth increase significantly between 2004 and 2014 – but only two percent of the population qualified as middle class. This was due to a small manufacturing base, and industries that generated employment with good wages but unequal shared wealth.

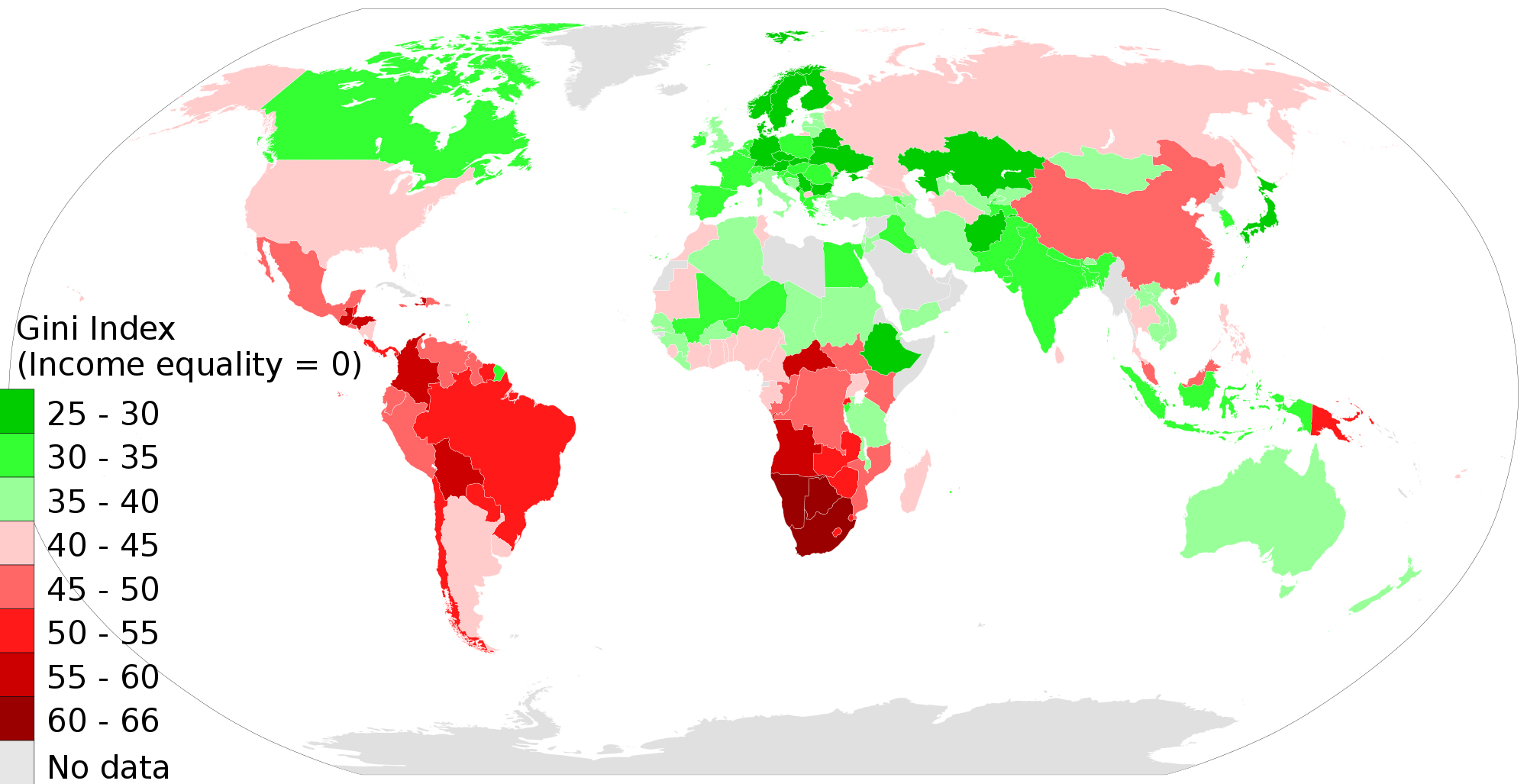

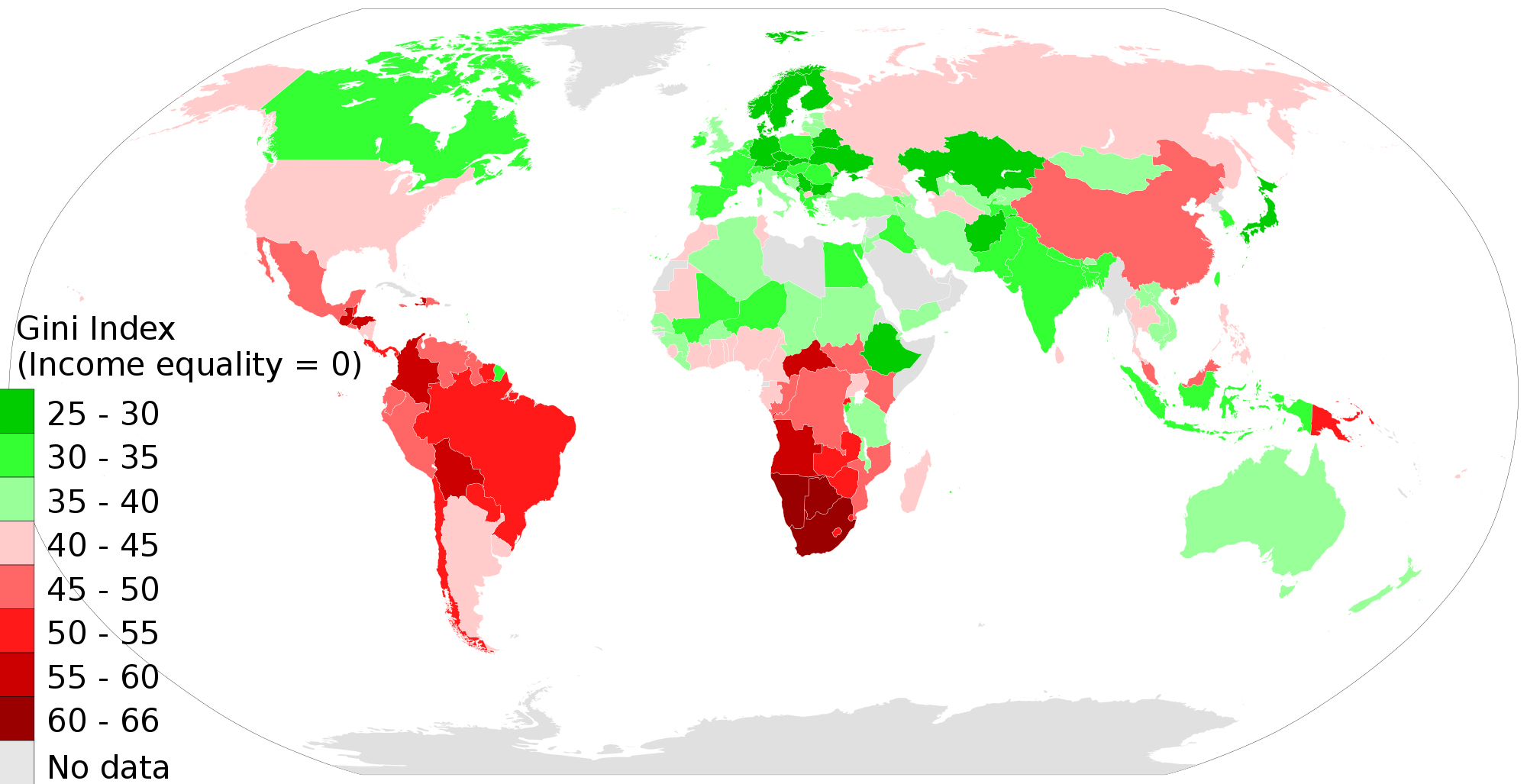

Unlike in East Asia, it seems that economic growth in Africa has been accompanied by growing inequality, which holds back both economic development and the development of the middle class.

A middle class can be both the cause and result of improvements in a country’s development levels. The AfDB’s 2011 study argues that the middle class is important not only economically but also politically, in that it is better able to hold government accountable. The middle class also invests in longer-term benefits such as healthcare and quality education, thereby expanding and diversifying economies through human and capital investment. It is now recognised that the middle class is not only important for economic development but also crucial for the maturity of democracies.

It could be said that the making of the Asian miracle was no miracle at all. A number of factors made it possible, particularly in Japan, South Korea and Singapore. As long ago as 1993 the World Bank argued that high growth in Asian economies was “due to a combination of fundamentally sound development policies, tailored interventions, and an unusually rapid accumulation of physical and human capital”.

In Japan high investment in human capital since the mid-19th century led to high productivity, subsequently increasing income. Japan made a conscious decision to catch up on technological development by creating modern transport systems and high-quality production machinery through the “Western knowledge, Japanese way” paradigm; scholars, particularly during the Meiji government (1852-1912), were sent to the West to learn about industrial development.

In South Korea, state-led development has been fundamental in decreasing inequality through policy interventions. Government policies resulted in higher and more equal distributed growth “than otherwise would have occurred”, according to the World Bank.

In 2000 the Korean government actively set about eradicating poverty, unemployment and inequality through focused socio-economic policies. A government employment subsidy helped many organisations create more employment and operate with more stability and since 2007, many non-profits have been certified as social enterprises and created employment.

Some countries in East Asia tried to establish development banks to assist financial institutions during economic recessions, as in 1950 and 1997. However in Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand these initiatives failed because their financial sectors were vulnerable. Japan and Singapore development banks helped expand financial markets because their financial institutions were robust and well capitalised. Such development banks could be useful in Africa if their financial conditions are closely monitored and protective systems developed to make them less vulnerable to financial crises. This could be instrumental in transforming informal economies.

If Africa is to develop its middle classes by emulating the East Asian model, it will need to do so economically – by targeting high growth while dealing with Africa’s high levels of inequality. Economic growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition for addressing high levels of inequality. While some level of inequality is inevitable, the extremely high levels seen in South Africa, Nigeria and Ethiopia represent a massive skewing of socio-economic well-being, and could result in uprisings among the poor. This is why high levels of investment in education are crucial in addressing inequality: education leads to improved productivity and higher earnings, which in turn boost the growth of the middle class.

Other policy interventions could include measures to address the effect of inherited inequalities; introducing a minimum wage to support improved living standards; supporting small to medium enterprise growth, which diversifies the economy and opens up more job opportunities; and measures, such as tax incentives, to expand the national manufacturing base, which generates jobs and tax income.

Each of these approaches involves challenges, costs and drawbacks, which must be calibrated according to context. But the bottom line is that only diverse and well-organised economies create sustainable, meaningful jobs.

MINENHLE MBANDLWA holds an honours degree in political science and employment law from the University of KwaZulu-Natal. He is currently doing a master’s degree in global studies at Doshisha University (Japan). His specialisations are anti-corruption studies, human development and human security