South Africa needs a grand coalition between its leading parties

South Africans recently voted in the fifth round of local elections of the democratic era, and the results have been widely seen as a tectonic shift in South African politics, with many holding that the main shock is the ANC’s loss of support. Looked at more closely, however, it is clear that the DA also lost significant support. Good Governance Africa’s (GGA) view is that these facts reflect an underlying situation of national crisis, which only a coalition between our leading parties can address.

After the results of this year’s local election, held on 1 November, were in, many analysts were shocked. The main significance of the results, they said, was that the ANC had lost significant support. Its proportion of the national vote had declined to less than a majority for the first time since 1994. However, this narrative misses the reality that support for the main opposition party, the DA, also declined to 21.65% from 26.9% in 2016.

The ANC’s record of having allowed state capture during the Zuma administrations, and its longer-term maladministration, corruption, and incompetence, are thought to have influenced many abstainers among its traditional supporters. The party has been in power for 27 years, and its ability to convince voters that it is succeeding in its mandate to improve their lives has diminished steadily.

Meanwhile, the DA has been in opposition at the national level for 21 years, and has led one province, the Western Cape, for about 12 years. Some analysts have argued that its losses represented a shift to the FF+, a much smaller party, reflecting voters’ lack of confidence in the DA’s ability to represent their interests.

Other results have also been thought to indicate that the recent local elections signal important changes in the country’s political landscape. The EFF’s support has risen to 10.31% from 8.9% in 2016, while support for the IFP increased to 5.64% from 4.25% in 2016. The outcome, however, is that the ANC controls 167 councils, the DA 24 and the IFP 16. Despite its larger proportion of support nationally, the EFF did not gain a single seat.

These figures are a sideshow, though. The main result of these elections is a clear indication that voters are — to use a traditional phrase — gatvol with both the largest parties. The fact that voters could not give a clear mandate to either party in about one third of our local councils clearly indicates this. How can this be?

GGA’s recent Government Performance Index (GPI) provides some answers. The GPI ranks the country’s 205 local municipalities on a range of 18 indicators covering categories such as administration, service delivery, planning and monitoring, and its metros on a range of 20 indicators that include an additional category, development. Service delivery was weighted as most important in the index because it reflects such things as access to piped water, a flush toilet connected to sewerage, access to electricity and weekly refuse removal.

As we noted in our report, issued just before the local elections, “local government is the level at which governance most directly impacts people’s lives through rigorous planning, adequate service delivery, maintaining infrastructure and proper financial management”. Put more simply, an important reason for the existence of councils at all is to provide these basic and essential services.

The results of the GPI ranking reflect this in some detail and can be consulted on our website. In outline, only in less than a quarter of municipalities do 95% of households have access to electricity. In about half of all municipalities, most households do not have weekly refuse removal. Only in a quarter of municipalities do more than 50% of households have access to piped water. Clearly, many of our councils are simply failing to do the work that they exist to do.

Most of the councils in the top 10 are run by the DA, except for one which is controlled by the ANC. Most of the councils in the bottom 10 are run by the ANC, except one that is controlled by the IFP. But these results do not reflect a total difference in governance quality between councils run by one or the other party.

Councils in the vast middle range between these two extremes are run by either of the parties, or coalitions involving them and local parties. Where the ANC dominates, a sorry tale of poor to very poor governance mostly prevails. Where the DA runs things, its successes are often due to its preference for delivering services in areas favouring its supporters.

Auditor General, Tsakani Maluleke

The Auditor General, Tsakani Maluleke, summarises this bleak state of affairs by reporting irregular expenditure of R26bn in the financial year 2019-2020, with only 27 of the country’s 257 municipalities receiving clean audits. Municipalities spent up to 46% of their income (including conditional grants) on salaries for staff and politicians and only 2% on maintaining infrastructure, according to Maluleke.

Given these results, calls have been growing for a more cooperative approach. Even given the low turnout for the recent local elections, support for the ANC and the DA still represents about 67.5% of the total vote. That’s a sizeable proportion, and in a democratic context, a good indication of how completely these two parties dominate the political landscape.

Yet, faced with clear evidence that the voters are not pleased, both parties are digging in their heels and arguing that they will not work with each other in any kind of coalition to fix the mess. They have cited various reasons, some of them reflecting mutual hostility and partisanship and some reflecting supposed difficulties in principle with the idea of a coalition between the two leading parties. As regards the partisanship, GGA believes that the evidence is clear. The voters don’t like the results.

As regards the matters of principle, we believe that these are largely misguided. Coalitions between the leading parties are not a political device that is appropriate only in times of dire emergency, such as war. In fact, many countries have been run, or continue to be run, by coalitions between leading parties. Among them are Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Northern Ireland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. It appears to have been forgotten, too, that South Africa’s first democratic government, under Nelson Mandela, was a grand coalition.

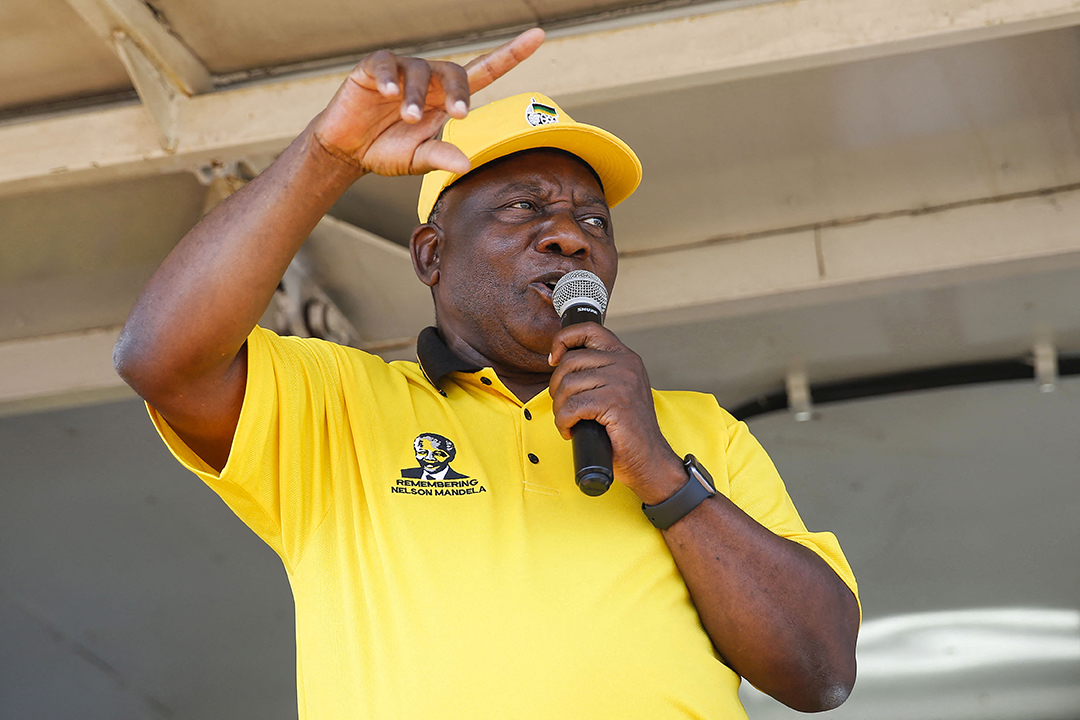

African National Congress President Cyril Ramaphosa addresses party supporters during a door-to-door political campaign ahead of the local government elections in Mabopane township north of Pretoria, on October 15, 2021. Photo by Phill Magakoe/ AFP

In some cases, such grand coalitions have been agreed to for specific reasons, often to address or overcome a political crisis. In other cases, they have become embedded in the political system. As the list above shows, they are not a device that is appropriate only for war or serious social conflict. Indeed, in many cases something different has been involved. Often enough, the formation of grand coalitions has been a major reason why societies have been able to resolve difficulties that have implications for the whole country.

It is true that grand coalitions have sometimes been introduced in times of war — the UK’s “national governments” during the first and second world wars being a case in point. However, this has been the exception rather than the rule. It is also true that grand coalitions face challenges for opposing political parties. They may fear losing clear party identity and, therefore, support from loyal voters; they may be concerned about the difficulties involved in negotiating coalition agreements; and they may worry about being able to take credit for successes.

Democratic Alliance (DA) Chief Whip John Steenhuisen addresses the crowd at the DA party manifesto launch at The Rand Stadium in Johannesburg on February 23, 2019. (Photo by GULSHAN KHAN / AFP)

Yet depending on the circumstances, there may also be many good reasons for considering a grand coalition. Opposed leading parties have often agreed to grand coalitions because this would increase their electoral competitiveness or put them in a better position to advocate for democratic reforms, or because doing so will improve their influence on policy formulation, enable them to use limited resources more effectively, or to reach agreement on programmes for government (National Democratic Institute, 2015).

The failings and inadequacies in our local government are a national crisis that reflects a malaise at all our levels of government. We believe that the tectonic shift in South Africa’s political situation as represented by the most recent local election results indicates that it is time for a super coalition, as we call it.

Both parties will have to compromise. The ANC will have to recognise that its de facto policies of tolerating incompetence, maladministration and corruption in government must come to an end. The DA will need to recognise that its deafness to the real issues and demands of our poor is a hindrance to improving local governance, and indeed an obstacle to improving our other levels of government. Both parties will need to learn to listen, as well as talk.

Intellectual tools, instruments, and advisory organisations for the successful negotiation of coalitions abound and are readily available. Where these are not enough, mediation is also a possibility, as was the case in Kenya in 2009, when an AU-brokered deal saw a grand coalition installed to bring peace to a violent confrontation.

It might be that our political grandees cannot see their way to accepting the necessity of addressing the national crisis in our governance. They might dismiss this proposal as unpalatable, but that would, in our view, be a position of unenlightened self-interest. The issues facing us are larger than that, and they demand greater political maturity. The national issue with which the country is now faced is one that neither party can fix on their own.

The video below contains an interview with the author, Richard Jurgens.

The video below contains an interview with GGA SADC Executive Director, Chris Maroleng.

Richard Jurgens is a former editor of GGA’s flagship publication, Africa in Fact, and has been appointed as editor of GGA’s peer-reviewed academic journal, The Africa Governance Papers. He spent 10 years in exile with the ANC in Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, as well as the Netherlands. He has worked in mainstream media, alternative media, the corporate world and for NGOs internationally and in South Africa. A published author with a memoir, a novel and several books of poetry to his name, he has a BA (Hons) in philosophy and is currently completing a Research Master’s degree in public policy studies at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Governance.