As the Southern African Development Community mission in Mozambique nears the end of its term, South Africa, as chair of SADC, called for a summit to be held on 4 and 5 April. Initially, Eswatini was included but its subsequent removal raises questions. King Mswati III agreed to a national political dialogue to address the crisis in his country during a meeting last year with President Cyril Ramaphosa.

This meant the process of the national dialogue formation would be included on the meeting agenda. But most, if not all, SADC member states strive not to have their domestic issues brought to the fore and become standing items on the SADC agenda as happened in previous years with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar and Zimbabwe.

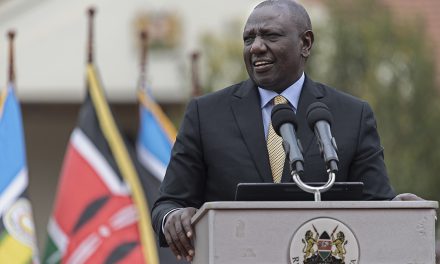

King Mswati III, Head of State of Eswatini, speaks during the 74th Session of the General Assembly at the United Nations headquarters in New York on 25 September 2019. Photo: Timothy Clary/AFP

Eswatini would therefore prefer to deal with its domestic issues outside the regional spotlight. It is the norm to invite a member state in question to an extraordinary meeting if they are not part of the troika. For instance, in the past when discussing issues related to the DRC or Lesotho, the same format was used: organ troika plus DRC or Lesotho.

As stated during his last working visit to Eswatini, Ramaphosa met Mswati. Ramaphosa’s visit sought to agree on a mechanism to assist the country in moving on from the deadly protests and a clampdown by the kingdom’s security forces.

During their deliberations, several issues relating to the political and security situation in the kingdom were discussed. A key takeaway from the deliberations was a resolution that the kingdom “will embark on a process that will work towards the establishment of a national dialogue forum”.

To assist with the facilitation of a national dialogue forum, Ramaphosa and Mswati agreed that the SADC secretariat will, in collaboration with the government, begin drafting the terms of reference for the national dialogue forum. This process is important as it will clarify issues such as:

- The composition of the forum;

- Incorporating structures and processes in the Constitution;

- The role of the parliament;

- Understanding the role of the Sibaya (a gathering called by the king to consult his subjects) to be used as the format for the national dialogue forum; and

- Confirmation of timelines and milestones.

- It was expected that Eswatini’s invitation to the meeting was to provide an update on how far the country is in initiating a national dialogue forum. Mswati, seemingly reluctantly, had agreed and “accepted the need for national dialogue” (albeit through an intermediary).

On the eve of the extraordinary organ troika meeting the public was informed that because of “the unavailability of the presidents of Botswana and Mozambique, the summit segment had to be deferred to a later date”. Instead, the meeting was converted to an extraordinary meeting of the ministerial committee of the troika plus Mozambique.

Curiously, Eswatini’s participation and invitation to the newly configured meeting was absent or revoked. Was this the opportunity Mswati needed to pull his country off the meeting agenda? It meant no progress report on the national dialogue forum was to be presented, thus keeping Eswatini’s domestic issues out of the glare of the regional spotlight.

One has to assume Eswatini’s omission from the agenda was more the result of a calculated tactic than a procedural oversight. This tactic might indicate Mswati’s efforts to keep control of the proposed national dialogue and not hand the process to SADC as a neutral entity.

Of concern is that a day before Eswatini’s participation was removed from the SADC meeting agenda, Prince Sicalo — a senior government official and the first-born son of Mswati — was petrol bombed. Sicalo is the principal secretary in the ministry of defence. This incident may be a sign that tensions between the state and citizens remain heightened. If the national dialogue forum is not correctly handled, it may spiral into similar outbreaks of violence such as the country experienced last year, with possibly worse consequences.

In her press briefing, South Africa’s international relations minister, Naledi Pandor, did not offer a reason for the exclusion of Eswatini. One can only assume it was at the instruction or insistence of Mswati. His delegation probably argued that those tasked with the formation of a national dialogue required more time.

Interestingly, on 12 April, Ramaphosa called for the postponed SADC organ troika meeting to be convened. However, unsurprisingly, Eswatini was omitted from this meeting and did not appear on the agenda.

The omission of Eswatini from the SADC agenda may reinforce the belief that Mswati intends to hold the dialogue on his own terms rather than in the interests of the country. Thus, limiting the chances of holding a successful national dialogue forum to heal the nation.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian on 20 April 2022.

[activecampaign form=1]

Craig Moffat, PhD is the Head of Programme: Governance Delivery and Impact for Good Governance Africa. He has more than 17 years of practical experience working for government institutions and multilateral organisations. He was previously employed by the South African Foreign Service, where he worked extensively at identifying and analysing security threats towards South Africa as well as the southern Africa region. Previously, he was the political advisor for the Pretoria Regional Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. He holds a PhD in Political Science from Stellenbosch University.