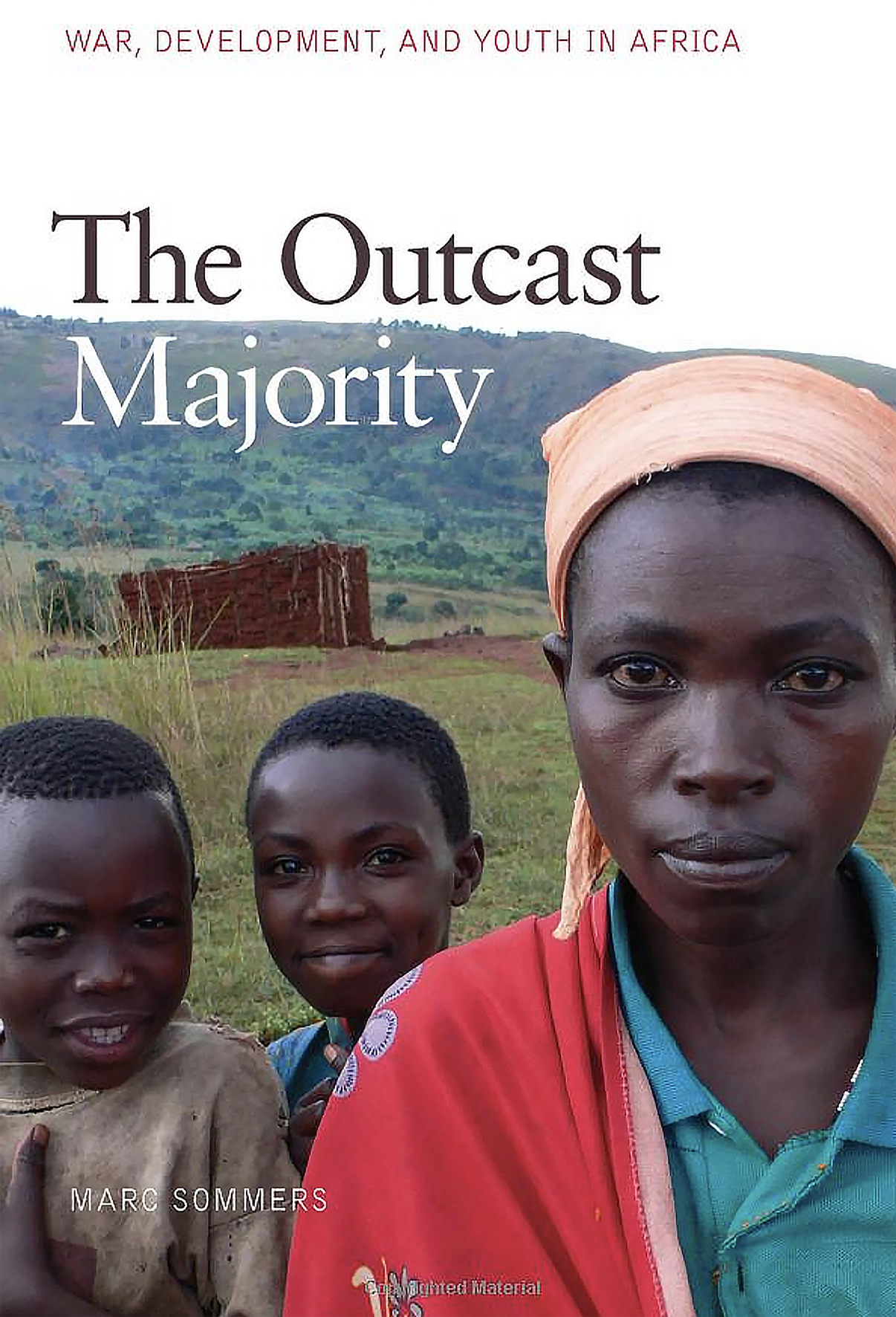

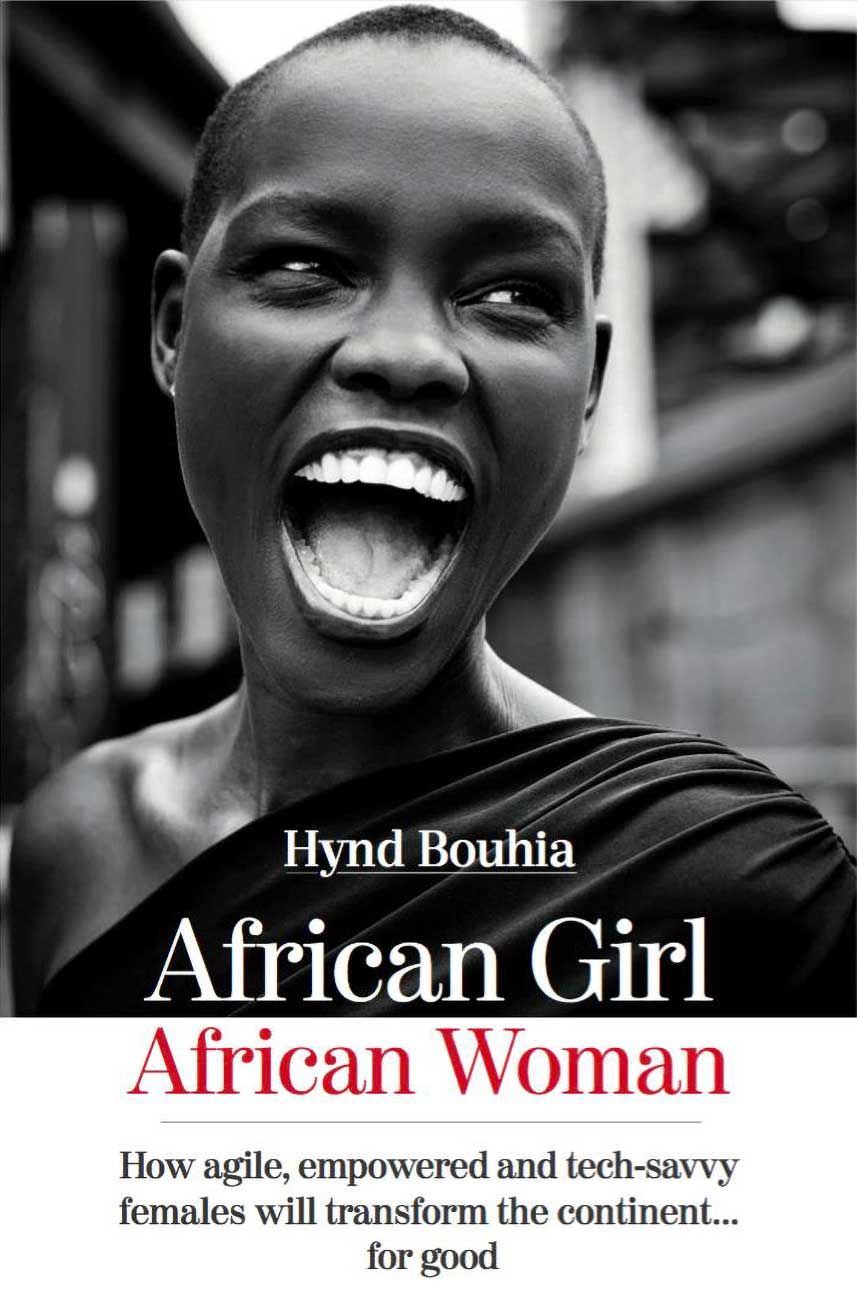

African Girl, African Woman – How agile, empowered and tech-savvy females will transform the continent for good by Hynd Bouhia; published by Rawan Publishing (2021)

African Girl, African Woman – How agile, empowered and tech-savvy females will transform the continent for good by Hynd Bouhia; published by Rawan Publishing (2021)

African Girl – African Woman explores the important role of women in science and technology in transforming the continent socially and economically – at the beginning of the fourth industrial and digital revolution (though some technologies have existed for 20 to 30 years).

Using an academic and motivational approach, the author Hynd Bouhia demonstrates the need to nurture African girls’ interest in science, technology engineering, and mathematics (STEM) from as early as six years.

Furthermore, through detailed examples of successful African female scientists, Bouhia highlights the importance of increasing the participation of girls in STEM subjects from primary to tertiary education. She also emphasises that human capital is a more powerful catalyst for technological change and wealth creation; it unlocks a nation’s capacity to create, innovate and build infrastructure resulting in industrial growth.

Africa has less than a decade to reach the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each of which underpins the role girls and women play in developing the continent. The SDGs encourage the education of girls in science and technology studies through SDGs 4 and 5. SDG 4 in particular demands quality education for 617 million children and adolescents who do not have the minimum competency for reading and mathematics, while SDG5 stresses gender equality, autonomy, and rights for women and girls.

Achieving the SDGs by 2030 will generate an estimated $12 trillion from potential markets while creating a whopping 380 million new jobs. This provides space for the African woman to play a central role in creating, shaping, and carrying out these jobs, with responsibility and care.

Cited statistics from as far back as 2015 indicate a gender imbalance in STEM subjects. For instance, although university STEM disciplines taught have increased, the female ratio of enrolled students shrunk from 37% in the 1980s to 17% in 2015.

As a result of this decline, private and public leaders across Africa are working hard to restore the gender balance in STEM fields, noticeably through universities aggressively encouraging females to pursue degrees in these disciplines.

Despite these efforts, Bouhia makes the point that confidence in STEM subjects stems from familiarity, which reiterates the importance of nurturing girls in STEM from a young age – instead of perpetually upholding the misconception, which often lacks evidence, “that boys simply prefer science and technology more than girls”.

By the age of 12, Bouhia writes, a girl usually aspires to a job or career for which she is stereotyped, so nurturing her in STEM subjects must occur early, as discouragement or damage often happens in her formative years. She may leave a promising career in an unpopular STEM discipline for fear of being ridiculed or marginalised. Similarly, worried about social rejection, she could conceal her brilliance or perform poorly in school to fit in or be liked.

Techniques to nurture a love for STEM include, for instance, a father treating his daughter equally by taking her into the garage to help fix a car engine, or trips to the hardware shop to buy electric cables or pipes to fix a leaking kitchen sink. Bouhia argues that such gestures begin the process of opening a girl’s mind so that she learns to navigate new disciplines, making her feel more autonomous in future choices and interests.

In addition, the nurturing process includes teaching her that cooking is basic chemistry, gardening is botany, that light is physics, and shopping involves calculation, while an interest in animals involves biology and may lead her to veterinary science. A love for electronic games or mobile phones can be the starting point for an interest in coding and programming. A passion for sport becomes an opportunity to show her that physical activity includes a combination of biology, chemistry, and physics in motion. Once the language of STEM becomes as common as a family member, Bouhia says, it becomes easier to grasp.

Repeatedly Bouhia makes the point that parents must prioritise advancing the girl child in education over marrying her off at an early age, uneducated and disempowered. But although African girls often lack a supportive family to expose and nurture them in this regard, hope is not necessarily lost since education does not occur in a vacuum. Parental support in the home can be supplemented and improved by training primary school teachers to encourage an interest in STEM subjects. Schools should also foster parent-teacher relationships that allow for dialogue to bring out the best in the girl child academically.

Likewise, mandates to increase interest in STEM subjects require governments and ministries to invest in the physical safety and psychological security required to keep the girl child in school. This support includes ensuring that schools have adequate and safe sanitary facilities, providing reproductive and health services, supplying hygiene kits, and hiring teachers able to handle complaints and offer counselling in girl-friendly spaces. Attending to these issues sets a firm foundation for a successful STEM career.

Equally, initiatives and networks spearheaded by various international and non-governmental organisations continue to propel the advancement of STEM careers, for instance, SheInvest and the 2X Challenge, launched by the European Investment Bank in 2019 to help finance innovations for girls. The World Bank’s $65 million Girl’s Education and Women’s Empowerment Livelihood (GEWEL) project offers scholarships to enable young African girls to return or remain in school. UNESCO’s female scientific networks include the Association of African Women in Mathematics (AAWM) and the International Network of African Female Engineers and Scientists (INWS), both created to encourage girls to explore STEM disciplines and careers.

While efforts made by national governments and various stakeholders within the continent to improve the uptake of studies in science and engineering at tertiary levels have succeeded, another challenge emerges for women after completing their studies.

African women remain professionally undercapitalised and undervalued in the workforce, often stuck in lower hierarchical positions than men. Those in business such as tech entrepreneurs, face additional challenges like accessing finance or business loans. But statistics featured in this book indicate that 27% of enterprises in Africa are created by women, and women in high-level positions yield a 34% higher return on investment.

Representation matters, and solving such challenges requires empowering girls and appointing more women in strategic leadership positions in parliament, government agencies, corporate boards, and academic institutions. Balance will result in a continent that empowers both men and women to revolutionise the future of science and technology.

This is an outstanding book in which the author educates and enlightens readers on the importance of adopting a holistic approach to educating a girl child. Bouhia not only discusses the formal structures necessary to advance the education of girl children in STEM, such as tech-oriented grants, science equipment, and incubators. She takes readers back to the drawing board by addressing how crucial the formative years of a girl child are in building her confidence and self-esteem, which sets the trajectory for her ability to succeed in STEM. The emphasis on the girl child’s formative years is also a call to action directed towards parents, caregivers, and guardians that constitute the family unit responsible for raising her. Since it is within such intimate settings limiting gender stereotypes have been perpetuated that then influence her career choices and how she shows up in the world.

Bouhia’s motivational writing style is inspiring and crucial to child development and she should consider publishing for non-academics – a handbook for parents, caregivers, and teachers responsible for nurturing girl children.

Ultimately, the book offers a balanced guide on how environments like the home, social communities, schools, and academic institutions can facilitate the development of a girl child to maximise her potential. A must-read for educators at primary and tertiary levels as well as academics in institutions of higher learning, and advocates for gender equality and the advancement of the girl child employed in private, public, and non-governmental organisations.

Sarah Nyengerai is an academic and freelance writer based in Zimbabwe with a strong passion for social, cultural, economic and political issues that affect women. She believes literary works form the foundation for the dialogue required to sustain momentums of change and aims to bring attention to such matters. A member of NAFSA (Association for International Educators) and Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE), Sarah is actively involved in the advancement of education for women.