In May 2021, Royal Dutch Shell (Shell), a British-Dutch multinational oil and gas company, lost what is considered a precedent-setting climate change case for oil companies. The Hague District Court in the Netherlands ordered Shell to reduce its carbon emissions by 45% from its 2019 levels, by 2030. This would align it with the commitments enshrined in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. However, the judgement gives Shell discretion as to how it implements the emission reduction objective. The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty signed by 194 countries and the European Union. The main goal is to limit global temperature increases to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, but preferably to 1.5°C. It provides a framework of technical, financial, and capacity-building support for countries.

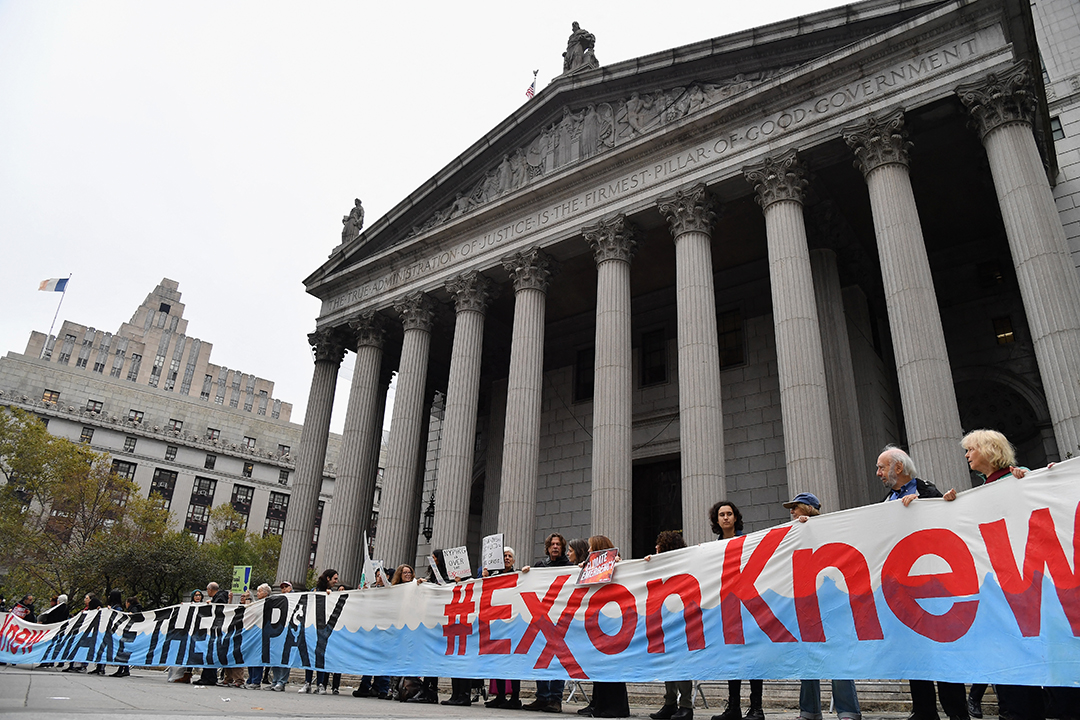

Climate activists protest on the fist day of the ExxonMobil trial outside the New York State Supreme Court building on October 22, 2019 in New York City. Photo: Angela Weiss/AFP

Activists vs Big Oil: Moving in the right direction?

There have been a handful of other victories for climate activists since May 2021, when ExxonMobil, an US multinational oil and gas company, lost two board seats to the activist hedge fund Engine No 1. Engine No 1 has been pressurising the company to introduce a better climate transition plan. In the early 1980s, ExxonMobil funded research that actively suppressed evidence demonstrating the reality of climate change, and lobbied against regulations that would have forced it to change commercial direction. It eventually acknowledged the climate change reality in 2014.

Climate activists also invested in British Petroleum (BP), and were able to garner approximately 21% support for a vote on short term emissions targets. The amount of support means BP’s board must report back to investors as to why they rejected these targets. Despite the growth of support, the motion has yet to gain over 50% support and be implemented. At Chevron, a resolution pertaining to Scope 3 emissions received support from 61% of shareholders.

Progress is clearly being made, but stakeholders and multinational oil companies must come on board to mainstream environmental considerations. The hydrocarbons sector is the single biggest source of global greenhouse gas emissions; therefore they have a significant role to play in the global transition towards green energy.

These recent developments show that Environmental, Social and Governance principles are pressurising extractive industry companies to become more responsible. They also demonstrate links between the ‘E’ (environmental) and ‘G’ (governance) elements in motivating for change. Environmental activists understand that unless they influence companies at board level, their concerns will not be heard.

Energy transition: A La La Land sequel?

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is focused on shaping a secure and sustainable energy future for the planet. Its recent landmark report provides a roadmap to reach a net zero emissions target by 2050. An unavoidable implication is an immediate end to all new fossil fuel investments. According to the IEA, such a target is essential for preventing global temperatures from rising beyond 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. However, Saudi Arabia’s Energy Affairs Minister, Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman Al-Saud, has labeled this proposal as the sequel to the movie La La Land. He asked: “Why should we take it seriously?”

Prince Abdulaziz’s question and challenge appears to be aimed not only at the IEA report, but also at the value of ESG principles for firms and countries. Why should countries in the developing world reduce their emissions, risk revenues by abandoning fossil fuel assets in the earth, and pause their industrialisation? Oil prices are expected to rise in the wake of global economic recovery from the impacts of COVID-19. These potential profits reduce the willingness of actors who stand to benefit to embrace the energy transition. At the same time, some firms have increased their investments in both fossil fuels and renewable energy sources in response to potential supply shortages of fossil fuels. Additionally, investment in renewables promises significant returns.

The energy transition will continue and, as in any such shift, there will be winners and losers. Many oil-wealthy developing countries will fall into the latter category. However, they tend to exhibit poor human development scores, and economic diversification is crowded out due to the way in which oil rents shape political economy outcomes. The energy transition poses a threat to the ruling elite who benefit from oil rents. Such a perception makes compliance with climate change imperatives more difficult. There is currently limited incentive for countries benefiting from oil rents to transition away from fossil fuels.

Mainstreaming ESG in the energy transition: Bringing more voices to the conversation to ensure a just transition

ESG integration, however, into the pursuit of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 can merge what appear to be irreconcilable interests. Bringing environmental and social concerns together, by including new stakeholders in corporate governance structures, offers a potential solution.

The primary focus of ESG thus far has been placed on environmental performance and corporate governance, often to the exclusion of social imperatives. This is partly due to the focus on the climate emergency. Environmental impacts of firms’ activities also provide more concrete and measurable metrics than social impacts. Similarly, corporate governance compliance is straightforward. So, how should firms pursue social performance improvements?

Including labour in corporate governance structures is very important when managing the losses that will emerge from the energy transition. Workers in carbon-intensive industries face the very real prospect of future unemployment as the energy transition progresses. This will have knock-on effects for local communities, as seen with coal mining communities in the United States of America. ESG principles offer a vehicle for concerned and impacted stakeholders to have a seat at the table. By being authentically included, workers can voice their concerns and propose potential solutions. Doing so will contribute towards a just transition for workers and communities who currently depend on fossil fuel industries.

Despite the potential offered by ESG performance standards, critics have pointed to the inconsistency of some fund managers behind the ESG movement. Without well-defined and universally applicable metrics, the risk of greenwashing remains significant. Additionally, they argue that sometimes membership in responsible investing initiatives can result in inaction. Stronger steps against greenwashing need to be taken to prevent ESG investing from becoming a hollow buzzword devoid of practical meaning.

The importance of achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement is illustrated by the devastating flooding in China and Germany, as well as the heat wave with runaway fires in the American Northwest. Climate change poses a significant threat to the wellbeing of countries, ecosystems, economies, and populations. Climate adaptation and the energy transition are, therefore, in the global interest.

While adherence to ESG principles and the pursuit of net-zero by 2050 is largely a voluntary action on the part of firms, precedents such as the Shell judgment present a potential legal and regulatory risk for firms that remain committed to fossil fuel extraction and consumption. These legal judgments provide a complimentary market signal that the ‘G’ of ESG will reinforce the momentum towards net-zero 2050. Countries and firms that resist this imperative will be left behind. The current ESG moment provides an opportunity to harness new opportunities and to create a truly just transition.

First published on BusinessLive

Vincent Obisie-Orlu is a Natural Resource Governance researcher at Good Governance Africa. He holds a BA in International Relations and Political Studies from the University of the Witwatersrand. His work focuses on natural resource governance of critical minerals, Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) issues, sustainable finance, and energy policy in light of the energy transition.