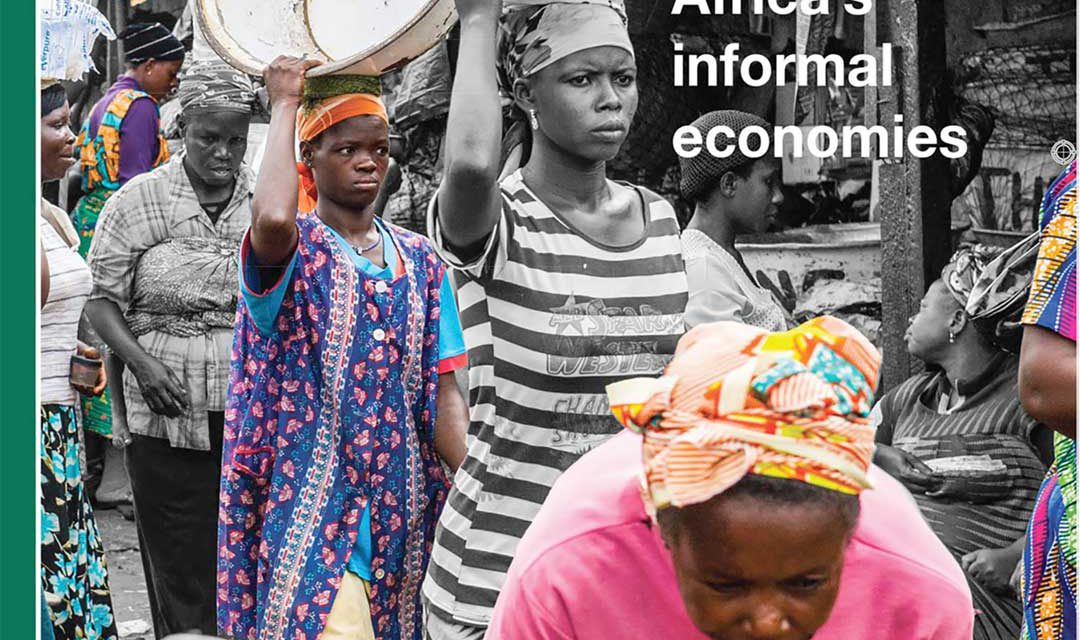

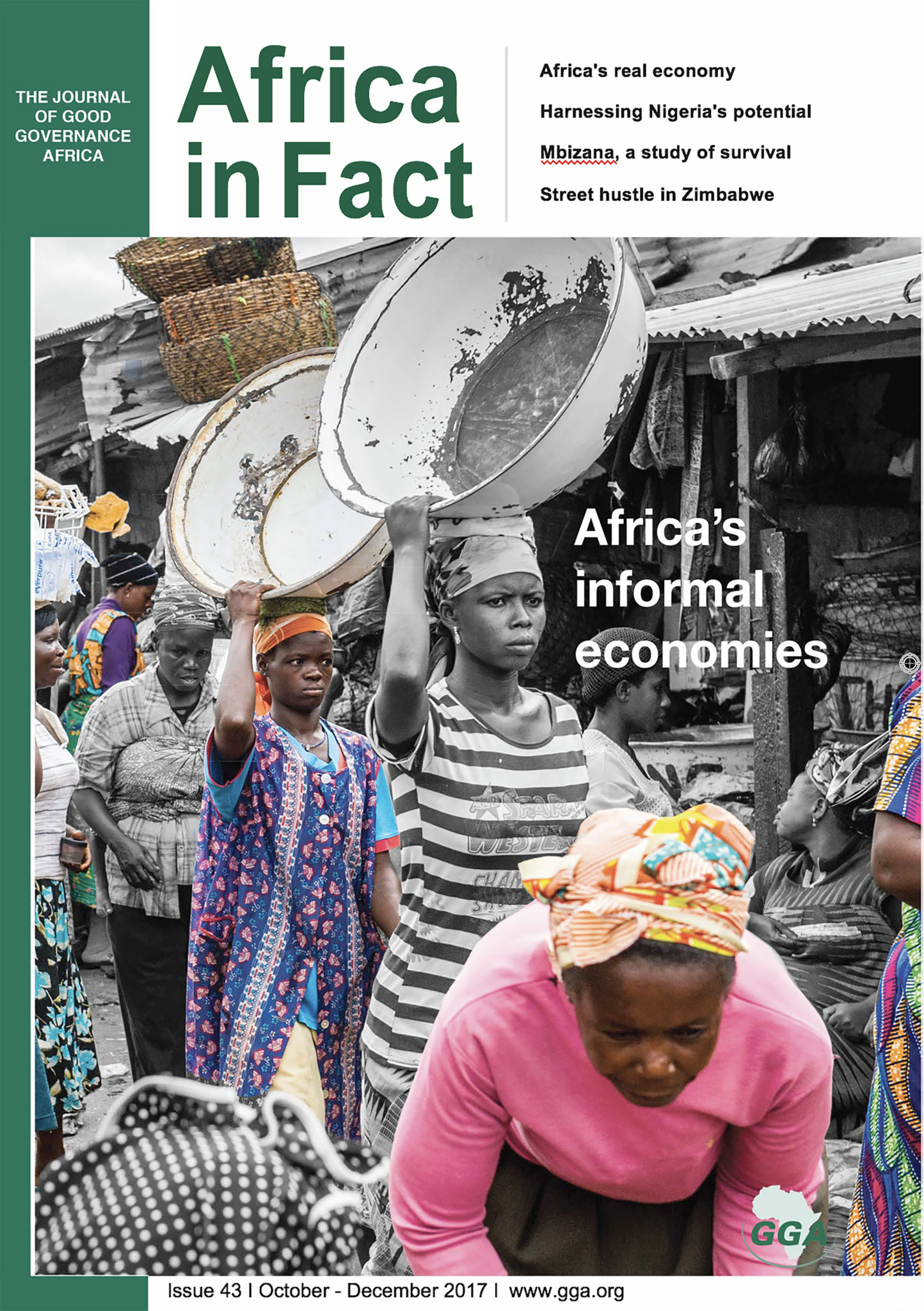

African governments and their formal business sectors often hold up the informal sector as the nemesis of formalised growth and organised development – yet for many citizens on the continent (and elsewhere), informality is a lifeboat in increasingly challenging economic seas. This edition of Africa in Fact explores this phenomenon, which is more complex than it might seem.

Kate Meagher’s comprehensive introduction proposes that the informal economy is the “real economy” of Africa, enabling the creation of 80-90% of new jobs on the continent even as its formal economy contracts. Dismantling the traditional stereotypes surrounding the sector, she focuses on the gains made in areas such as self employment and gender affirmation for women. Do African governments take an instrumental attitude to their informal economies, or are they seeking synergies? Have a read and draw your own conclusions!

Ronak Gopaldas argues that the formal sector could help build a more enabling business environment for informal business, thereby also helping the overall economy. Toby Shapshak shares the success story of mobile moneylending to informal traders in Kenya, while Blamé Ekoue focuses on taxation and the informal economy in Togo, where the state is faced with a trade-off between increasing levels of tax collection and the need for strategies that enable informal traders.

Clár Ní Chongaile reminds us of the human face of informal traders, the so-called jua kali who “labour under the fierce sun”. Consultation is key to building informal livelihoods, she argues. Collins Mtika, meanwhile, reveals that the Malawian government wants to recover money lost through corruption by taxing informal traders. Victoria Okoye, writing about Kumasi, Ghana, documents a 90% reduction in revenue for informal traders relocated by city authorities.

Writing about the informal transport industry in Freetown, Jamie Hitchen demonstrates how short-termism cripples initiative – exemplified by that city government’s attitude to transport regulations. Yet, nothing epitomises the human cost of state regression quite as much as the example of Zimbabwe, as captured by Barnabas Thondhlana. There, thousands of businesses have closed over a handful of years, unemployment is estimated at 85%, and informal trading offers many their only opportunity for a livelihood.

Gavin Hilson, writing on artisanal and small-scale mining, suggests that international awareness of informality has never been greater – in the face of the paradox of great mineral wealth accompanied by dire poverty. Policy development can be both the solution and the problem: Zambia is a positive case in point.

Contrast this with the eastern DRC. Ben Radley outlines the plight of informal mining workers who work in serfdom under powerful social and security forces (statal or otherwise), often for a pittance, just to survive. Yet the government shows mining MNCs considerable generosity. In fact, an awkward but vital interdependence exists between formal and informal mining there.

Meanwhile, as Perrine Massy’s article shows, Tunisia is chasing traders away even though the country’s informal economy brings in over one third of GDP. Seven years on, their situation – exemplifed by the tragedy of Mohamed Bouazizi, a trader who set himself alight in protest against police harassment in December 2010, sparking the Arab Spring – appears to have been forgotten.

Drs Asnake Kefale and Zerihun Mohammed write about Ethiopian migrants to South Africa. That country’s population is approaching 100 million, remittances accounted for more revenue than exports in 2016 and a key driver of migration, especially southwards, is poverty. Writing about a city in Somalia, Emma Lochery reveals how private power generators have transitioned from informal, private arrangements to organised multi- million dollar operations with which the state cannot compete.

GGA has also contributed research to this edition. Fisayo Ayo, from our Nigeria office, argues that the government needs to engage with the enormous power of its vast informal sector. Meanwhile, our SADC centre partnered with the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (SLF) on a business survey in the municipality of Mbizana, Eastern Cape, as part of a broader study of local government performance in South Africa. We learned that there, for many, micro-enterprises are not enough to sustain people who remain dependent on social grants.

Dr Leif Petersen, SLF director, delves into the “spaza shop” (informal retail) economy of South Africa. He shows that in some places, spazas are on the downturn and diversification is on the up, while there is a disturbing lack of local ownership of these stores. In a related piece, Caitlin Tonkin reviews the innovative leisure economy in Eveline Street, Windhoek, presenting a case study of how “social re-imagination” can help to realise the transformative potential of informal business activities.

Last but not least, Ryan Devlin gives us a picture of African street vendors in New York, who face big power interests. Yet they are organising, and continue to ply their wares, despite the current climate in the USA.

We thank Phillipe Marcadent at the ILO, who graciously provided the latest ILO data on informal economies and allowed us to use some forthcoming material. Numbers date rapidly and this up-to-date information allows us to ride the crest of the knowledge wave with you.

Africa’s informal economy is, for many, centrifugal to their lives and livelihoods. Building on this, GGA intends to collaborate with the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design at George Washington University on an innovative series entitled “Equity, Culture and Community”, in which informality will be engaged. Our SADC centre will also hold a workshop on participatory democracy and the informal economy in October, to bring together various local and international stakeholders for discussion directed at tangible outcomes.

Our forthcoming issue, dedicated to Africa’s plentiful natural resources, is due for release on bookshelves on January 1, 2018 and will mark a move away from the current free subscription and distribution model. On behalf of GGA, I would like to thank our readers and subscribers, thus far. Please do continue your support by purchasing copies of AIF next year, or by becoming members of our NPO governance community!

Wishing you all a productive remainder of 2017 and peace and goodwill into the New Year.

ALAIN TSCHUDIN is a former Executive Director of Good Governance Africa. He is a registered psychologist with Ph.D.s in Psychology and in Ethics. He was a Swiss Academy Post-doctoral Fellow at Cambridge and oversaw the Conflict Transformation & Peace Studies Programme at UKZN for several years. He has broad research and community engagement interests and has worked for various universities in Africa and Europe, with the European Commission, with local and international NGOs, as CEO of a leadership development agency, and as lead consultant for Save the Children and UNICEF, most recently as Child Protection Assessment Coordinator for Northern Syria. Alain has an adjunct association with the International Centre of Non-violence (ICON) and the Peacebuilding Programme at the Durban University of Technology.