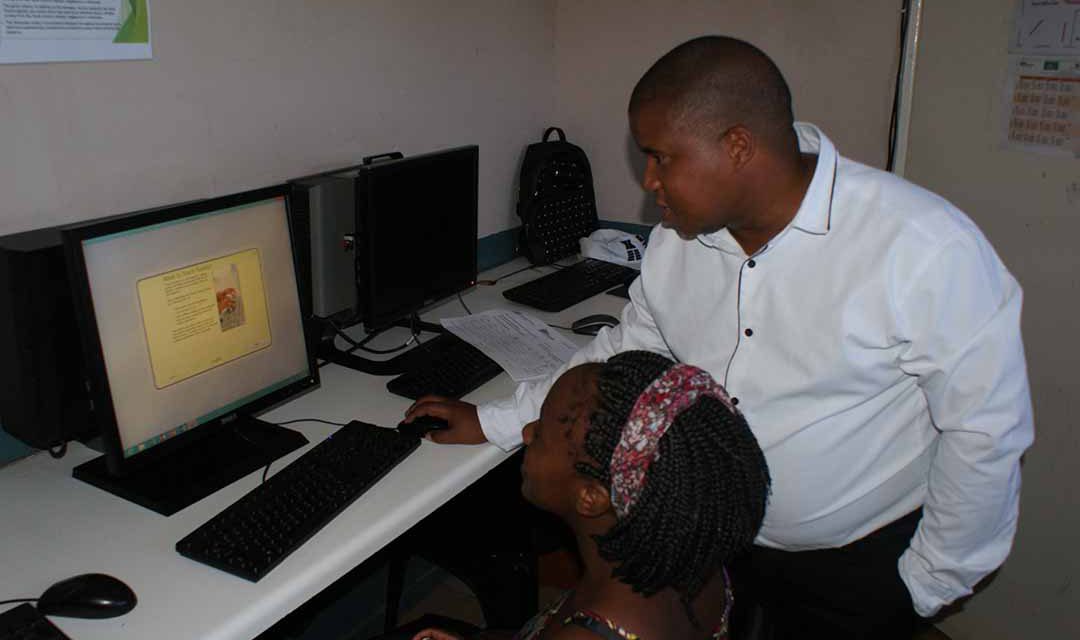

Lesego Tshabalala, CEO of Get Informed! Youth Development Centre Photo: Fred Khumalo

From the sticks to the ghetto, to prison, back to the ghetto and now in the boardroom.

That’s how, in these days of social media and short attention spans, you would summarise the life of Lesego Tshabalala, CEO of Get Informed!, an NPO that is fast gaining a name for itself in changing the lives of young people in the East Rand townships of Tembisa and Daveyton.

But, of course, life stories are more intricate, more nuanced than a twitter entry.

Which is why, to better appreciate the meaning of Tshabalala’s journey, we have to claw back to 1948 when Alan Paton published his novel Cry, the Beloved Country which prophesied how the forced removal of black people from their ancestral lands would forever change the face of the typical black family, this in turn resulting in a domino effect on society as a whole.

In the hauntingly beautiful opening pages of Paton’s book we see hordes of black people being forced into overcrowded patches of land, which soon succumb to overgrazing.

“Down in the valleys women scratch the soil that is left and the maize hardly reaches the height of a man. They are valleys of old men and old women, of mothers and children. The men are away, the young men and the girls are away. The soil cannot keep them anymore.”

Paton’s words came to me as I sat listening to Tshabalala telling me about his own journey from the rural village of Maboloka, near Brits, in the North West where he was born in 1985.

“I was raised by my elder sister and brother until the age of 12, as both of my biological parents passed away when I was only two years old.”

In 1996, he relocated to Daveyton in the East Rand to live with his aunt.

“Moving to Daveyton definitely made an improvement to the quality of our lives as a family,” Tshabalala remembers, “but of course life in this new environment was overwhelming.”

He shared the home with an extended family, an overcrowded space. The neighbourhood itself was also busy, and strange to an impressionable young boy.

He did not know it then but tragedy was slowly circling him, an inevitable reality for many young people growing up in overcrowded, fast-paced, dog-eat-dog environments.

These transitions – which can be a move from a township to a suburb, or from primary school to high school – are attended by peer pressure. In the heady cocktail of peer pressure there are drugs, alcohol and other stimulants that are supposed to mark one as a “cool” youngster or a “bhari” or “moegoe” – the antithesis of cool.

Tshabalala soon got into street culture, bowing to peer pressure. Before he knew it, he had been arrested and sentenced to 10 years in jail.

“It’s not something I want to talk about now; I am focused on building, and helping youngsters to avoid what I went through,” he says, refusing to get into the detail of his conviction.

It was while in the junior section of Leeuwkop prison that he was introduced to Khulisa, an NGO that seeks to help young people with everything from rehabilitation to HIV/Aids and drug counselling. He was 16 years of age at the time.

Having served three years of his sentence, he was released in 2006. Back in the community, he started working for Khulisa as a facilitator in Tembisa schools. Later, he travelled countrywide doing the same.

What he immediately identified was a lack of guidance among the youth, both in terms of social and career paths. As a result of these challenges, many young people – even those who have completed their matric – get stuck in the community, unemployed.

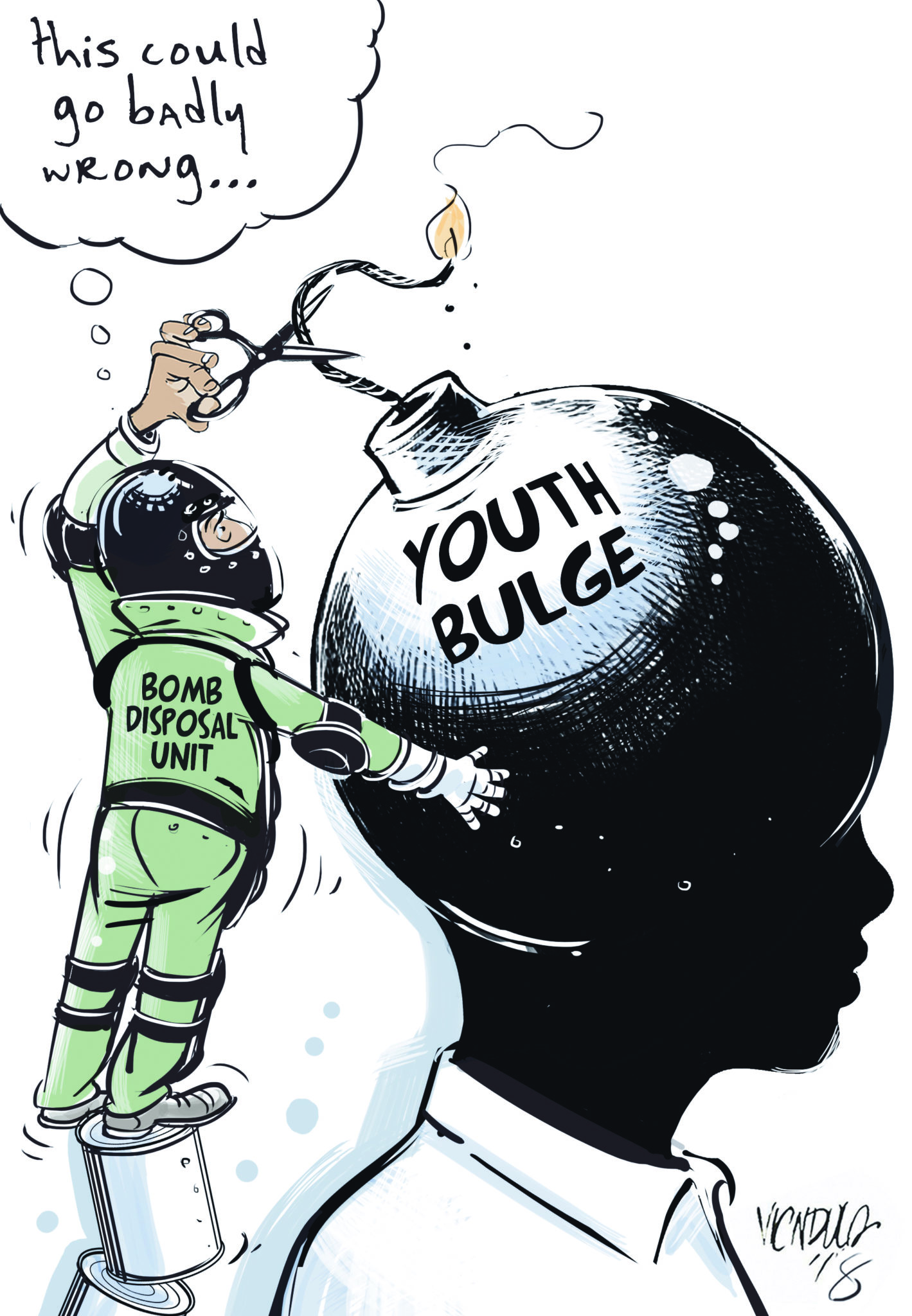

In a 2017 analysis of statistics on the country’s economic performance released by StatsSA, Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings commented, “South Africa’s official unemployment rate has remained at its highest level since the data series started. The previous record high was 27.1% recorded in the third quarter of 2016.”

According to the expanded definition of unemployment, which includes discouraged workers, the unemployment rate is 36.6%, up from 36.4% in the first quarter of 2017.

“In addition, the unemployment rate for the youth younger than 25, using the expanded definition, is a shockingly high 67.4%,” Lings said. “Clearly, the rate of youth unemployed has become a national crisis, with significant social, economic and political implications.” He said the high rate of unemployment contributes to the social tension and anguish experienced in South Africa on a daily basis, especially among the youth.

It was against the background of this unemployment crisis that Tshabalala started Get Informed! Youth Development Centre in 2012, following a solid mentorship from Khulisa.

The centre, which now has a second branch in Daveyton, is a one-stop advice hub for unemployed young people. They visit the centre to receive learnerships that equip them with basic computer literacy, how to write a CV, and call-centre training.

Visit the centre on any given day and the place resembles an upturned beehive with young people coming in and out. But there’s order. The computer training room, which can take at least eight people at a time, is business like. A trainer moves from one computer terminal to the next, offering advice here, extending a word of encouragement there.

The centre gets at least 500 young people ready for the job market every quarter. Many of the trainees get immediate employment at call centres and retail stores as cashiers. Some have also been taken up by the Mr Price Foundation for further training in the retail sector.

Eighty percent of the graduates are females. Tshabalala, who now has a staff of 10 people working with him, said the centre manages to find placements for at least 70% of their trainees each quarter .

“We do realise that young men from the community are getting left behind, mainly because the skills training that we offer is not traditionally associated with males; but right now we are in the process of designing courses that would appeal to them,” he said.

At the time of the interview the centre was about to launch a training course for forklift operators. “We are hoping to do more in future, but we are handicapped by a shortage of funding as some of the skills can only be taught if we have physical tools for the skill in question.”

Another immediate challenge for Tshabalala is permanent accommodation for Get Informed!. Now in its fifth year, and having produced at least 5,000 graduates since its inception, Get Informed! is still renting premises from the local municipality. Not only is this eating into the organisation’s funds, it is also a source of anxiety.

“We’re always looking over our shoulder when it comes to accommodation,” he said. “Although we are offering a valuable service to the community, which we believe is definitely in line with the government’s social development policies, we can never foretell how the political principals would like to utilise their building in future.”

Tshabalala, who has been furthering his studies, acquiring certificates in such diverse areas as auxiliary social work and basic project management, is passionate about gradually laying solid foundations for young people so that they don’t have to go through the personal struggles he had to.

“Every generation must learn from the ones before it to avoid the pitfalls of the past,” Tshabalala said. “But more importantly, those who come after us must stand on our shoulders so they can see far into the distance. The challenge we are grappling with now is to make sure that the foundation on which we stand is solid.”

FRED KHUMALO is a seasoned journalist and award-winning author of the novels Dancing the Death Drill and Bitches’ Brew, among other titles. With an MA in creative writing from Wits University, he is also a Nieman Fellow (Harvard University, 2011-2012). A stage adaptation of Death Drill had its world premiere at Nuffield Theatre and Southampton