Among the highest salaries in the world are those of public servants, many of them in African countries struggling with grinding poverty, underdevelopment and stagnant economies.

At the pinnacle of every public service are elected officials topped by presidents, whose remuneration packages are eye-watering in some cases, and explain the lavish lifestyles for which some, like Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo and his son, Vice-President Teodoro Nguema Obiang, have gained notoriety.

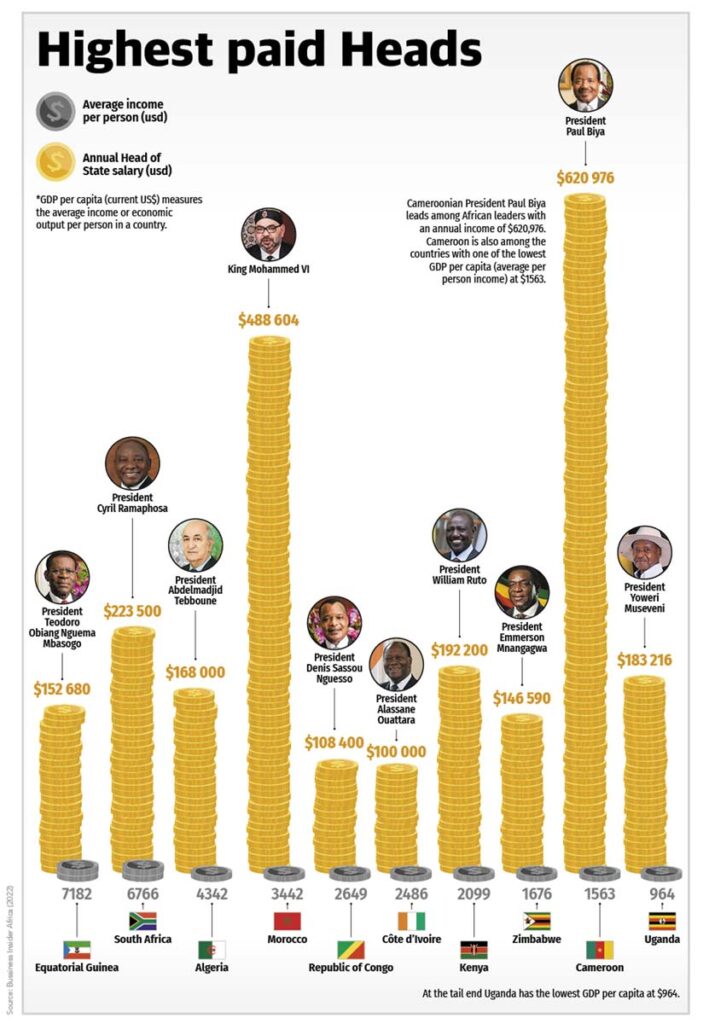

According to a May 2022 report by Business Insider, which scoured data from country websites and organisations like the International Monetary Fund and CIA World Factbook, Cameroonian president Paul Biya earned an estimated annual salary of $620,000, followed by King Mohammed VI of Morocco ($480,000), and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa ($223,000).

President Biya’s salary is substantially more than the salary of the US president, set by law at around $400,000, bearing in mind that the US boasts the highest GDP in the world at more than $20 trillion. Other Western presidents’ salaries range from around $75,000 to $250,000 or more per year; the Norwegian prime minister’s salary, for example, is approximately 1,700,000 NOK ($162,000) per year, while in some eastern countries, like India, presidents are not paid a salary but rather receive a stipend, or daily allowance, for expenses. Russia’s Vladimir Putin officially claims an annual salary of $140,000 (but he has vast personal wealth, reportedly worth $200 billion).

The public sector wage bill the world over typically makes up a significant portion of government expenditure. In 2022 in the UK, for instance, the public wage bill accounted for around 25%-30% of total government spending.

But questions pop up where wages are remarkably generous in economies where public services are sorely lacking. In South Africa, for example, 55,000 of the approximately 1.2 million public servants earn more than R1 million annually, according to Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana’s medium-term budget policy statement last November.

Still, while the tax-based rewards to a country’s publicly elected office-bearers and the civil services they oversee might be morally questionable, do these inflated wages amount to corruption?

The answer is complex and multifaceted. Wages for public officials, elected or appointed, are regulated by laws and rules designed to ensure fair remuneration for government employees. That salaries and pay increases are high is not in itself the problem, and indeed, it might lower the risk of corruption according to the “fair wage model” developed by American economist George Akerlof, which holds that officials engage in corruption only when they see themselves as not receiving a “fair” income.

However, in cases where public service salaries verge on the absurd, are disproportionate to packages for commensurate roles in the private sector, or are highly unequal within that public service, corruption can and does raise its opportunistic head.

The World Bank, in a 2021 survey titled ‘Effects of public sector wages on corruption’, found that while increasing the wages of public officials could help reduce corruption, in countries where public sector wages were highly unequal, the risk of corruption increased.

In other words, poorly paid public officials, especially those managed by officials on bloated salaries, may be more tempted to engage in activities like bribery and procurement fraud.

Evidence from across Africa bears this out. Bribery, nepotism, and favouritism in government appointments and procurement processes are widespread, particularly in poorer countries, including South Sudan, Burundi, Niger, Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Malawi and Mozambique, where job opportunities in the private sector are extremely limited.

As Karam Singh, executive director of Corruption Watch told Africa in Fact, “In a stagnant economy, there are different kinds of rent-seeking activities in proximity to the public service, with people grappling for positions because the public sector is the ‘only show in town’.

“Where you see that those who fill those positions don’t have the requisite skills or capabilities as their counterparts in the private sector, that’s a red flag, an indicator that while not in itself corruption, these appointments and related salaries are likely to be unsound, profligate, and unsustainable,” says Singh.

In South Africa, public wages are regulated by the Department of Public Service and Administration, and in areas like education and healthcare, they are generally lower than commensurate jobs in the private sector. However, at the top layers of government administration – like the job of mayor of a large municipality – the upper salary limits reach more than R3 million per annum. Secretary to Parliament Xolile George earned R3.177 million ($158,230) inclusive of benefits over the 2022/23 financial year, according to the national legislature’s annual report released at the end of 2023.

Part of the problem is the structure of the public service, which Professor Jakkie Cilliers from the Institute of Security Studies (ISS) describes as “the Taj Mahal rather than the Eiffel Tower” (i.e., top-heavy), as well as a lack of accountability in job screening, recruitment, and promotion in civil service ranks.

“Remuneration is not the issue. It is more about competence and accountability, both of which have been undermined by how the government manages things, the impact of its labour dispensation (which tilts the balance of power significantly in favour of the employee), lack of consequence management – which starts in Cabinet – and how the country is pursuing black economic empowerment, which is hugely necessary in South Africa, but we do it based on colour alone,” he says.

This sentiment is echoed in the observation by Paul Hoffman, advocate, author and director of the NGO Accountability Now, in Terence Corrigan’s article in the previous issue of AIF, who points directly to cadre deployment as the root of dysfunction in regional and local government. Cadre deployment, Hoffman adds, is a violation of South Africa’s Constitution, which requires that “no employee of the public service may be favoured or prejudiced only because that person supports a particular political party or cause”.

The Public Service Commission and some of the bargaining councils receive many complaints along the lines of nepotism and favouritism, confirms Dr Sarah Meny-Gibert, leader of the State Reform Programme at the Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI). “Sometimes inappropriate appointments are isolated cases of nepotism, while in other cases it involves the layering of political factions into the public administration.” Illicit or non-compliant procurement tends to follow suit, and this is where the real corruption lies, she says.

Overpayment, nepotism, and procurement fraud afflict public services throughout the continent, to varying degrees. In Kenya, salaries for the country’s top public officials have been contentious for years and came to a head last November when the country’s national Controller of Budget, Margaret Nyakang’o, called for an audit to look into what she termed “budgeted corruption” after she found that the salaries of senior public servants, including President William Ruto, had been inflated to three times more than they were supposed to receive.

President Ruto’s gross monthly salary is reported to be 1,546,875 shillings ($11,000) after he and other state officers received a 14% salary hike, announced by the Salaries and Remuneration Commission (SRC) last June.

Shortly afterwards, Nyakango’o was arrested and charged with fraud herself, but the case was halted and widely slammed as a sinister effort by government forces to shut her down.

The SRC tagged Kenya’s public wage bill in Kenya at Sh1 trillion ($6.25 billion) in 2022, a figure inflated, no doubt, by the employment of “ghost” employees (people on the payroll but who no longer work for the public service), an issue highlighted in the Auditor-General’s 2021-2022 report as well as by the State Department for Public Works.

Kenyan Auditor-General Edward Ouko, in his 2019 report titled ‘State Capture: Inside Kenya’s Inability to Fight Corruption’, put it succinctly, writing: “Is our budget actually loaded with corruption? It fits the theory of a highway which has many exit lanes, and corrupt individuals know how to manipulate these exit lanes.”

Absentee and ghost workers also plague the public payroll in Nigeria, where the federal government’s wage bill has continued to increase, totalling N35,609 trillion ($22,2 trillion) from 2016 to 2021, according to the 2023 ActionAid report titled ‘Trends in Public Sector Wage Bills’, while the share allocation to agriculture, health, and education continues to fall below expected global minimum benchmarks.

“Each time they give me the payroll number, I get so frightened. Where am I going to get the capital to develop the infrastructure we desperately require if the payroll is consuming all the revenue?” asked Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu at a press conference in Abuja last September.

This speaks to the crux of how an excessive public wage bill erodes good governance; it not only creates a deficit in the funding available for much-needed public services, but also compromises funds for training, capacity building, and improving institutional efficiency. Weakened public institutions with inadequate checks and balances make it easier for corruption to thrive.

In addition, and more insidiously, it corrodes the social norms and values that hold communities together, deepening inequalities and driving conflict.

The solution lies in implementing transparent and fair salary structures that are commensurate with the responsibilities and qualifications of public servants, strengthening anti-corruption laws, and investing in public institutions so they can better ensure accountability.

Cutting the fat from the public payroll is imperative, not only to make more resources available for citizen services but to ensure the public service itself is sustainable, suggests William Gumede, associate professor at the Wits University School of Governance.

Writing in South Africa’s Sunday Times last December, Gumede said, “[Public servant] jobs, wages and benefits will be the first to be cut in the austerity programmes that will be enforced to combat state failure, fend off economic implosion and deal with public revenue shortages… Public servants must understand their ‘iron rice bowl’ (guaranteed lifetime employment) will collapse unless the country puts an end to corruption, incompetence and policy populism.”

As the proverb goes, “the waste of money cures itself, for soon there is no more waste.” – MW Harrison.

Helen Grange is a seasoned journalist and editor, with a career spanning over 30 years writing and editing for newspapers and magazines in South Africa. Her work appears primarily on Independent Online (IOL), as well as The Citizen and Business Day newspapers, focussing on business trends, women’s empowerment, entrepreneurship and travel. Magazines she has written for include Noseweek, Acumen, Forbes Africa, Wits Business Journal and UJ Alumni magazine. Among NGOs she has written or edited for are Gender Links and INMED, a global humanitarian development organisation.