Restless Development youth delegates attend the forum ‘African Youth: Fulfilling the Potential’ hosted by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation in Dakar on 11 November 2012. Sylvain Cherkaoui for The Mo Ibrahim Foundation via AP Images.

Recent years have seen an increasing popular appeal of youth uprisings in Africa. Some believe this to be the effect of the Arab spring, giving rise to the term the “African Spring”. While dissatisfaction with socio-economic conditions has been a key motivator behind these uprisings, frustration with the current political leadership is at the centre.

Young people are often accused of not conforming. But should the youth really attempt to conform to the existing social order? Is non-conformity and disruption always negative? Perhaps, it is unconditional conformity that is Africa’s main problem, and non-conformity is the solution. Maybe it is time to think beyond the existing structures and stop asking whether change is feasible, but rather how to make it happen. The main risk that the continent is facing may not be the failure to accommodate youth within the structure, but the failure to understand that there is a fundamental fallacy in attempting to do such a thing in the first place.

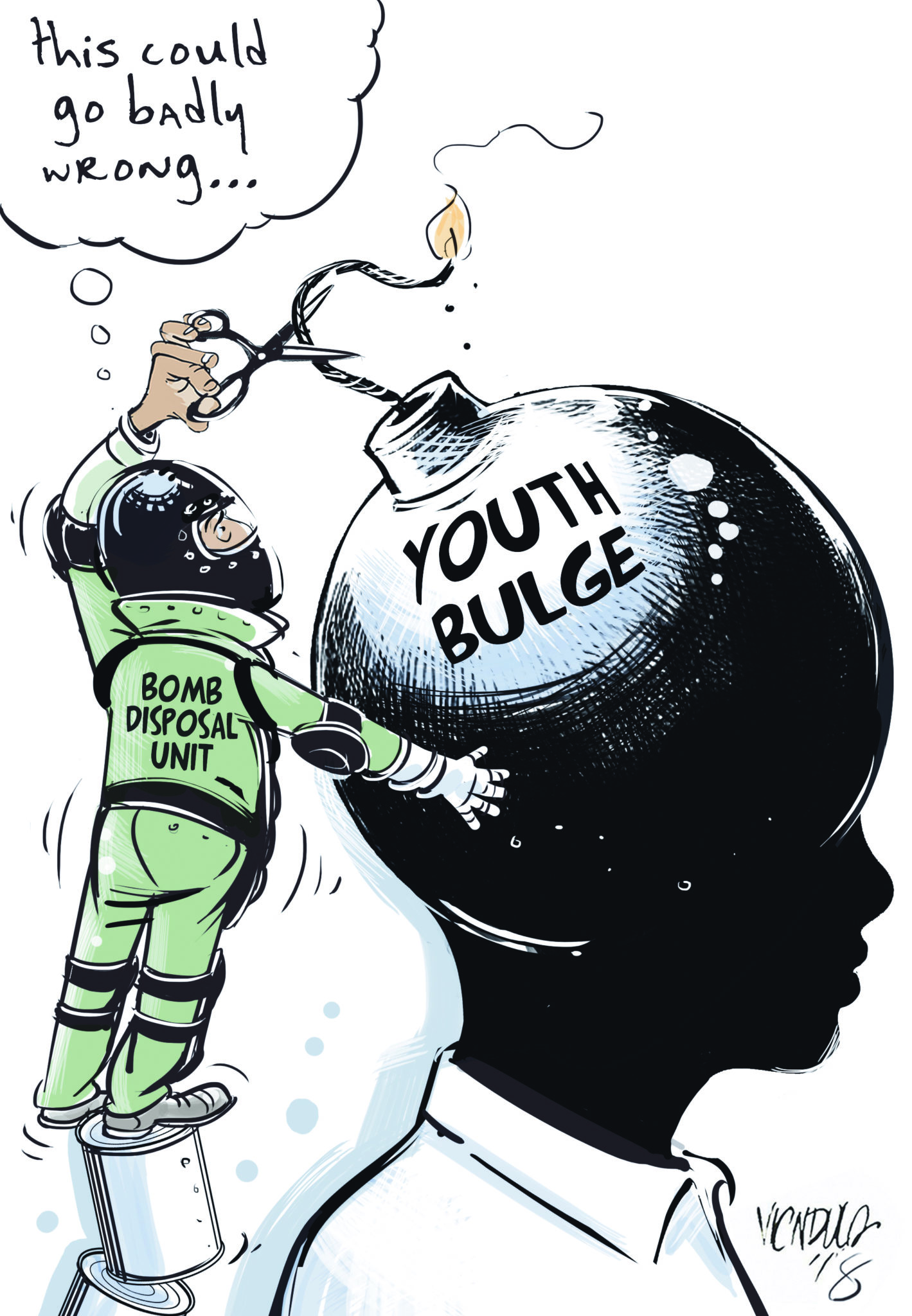

In an era when democracy is the norm, the greedy current leadership’s desire to prolong their stay in power does not sit well with the people, and even less so with the youth. Considering that 65% of Africa’s total population is comprised of youth – of whom 35% are between the ages of 15 and 35 years old, according to a 2017 study by the African Union Youth Division – the common narrative raises the question whether this could be a blessing or a curse for the continent. Is it a ticking time bomb or an opportunity?

This article explores the recent uprisings of youth movements, and the prejudice that labels this phenomenon as a non-conforming and disruptive strategy, to better understand how youth are carving space for themselves in both private and public spaces. The article specifically focuses on southern African movements.

There is no doubt that Africa is standing at a crossroads. Whether this will result in its rise or its downfall depends primarily on the youth, and secondarily on the capacity of the existing political and socio-economic structures to accommodate the growing youth population. With 60% of Africa’s unemployed being young people, according to a 2017 study by Kingsley Ighobor, a downfall seems likely.

The commonly advocated solution is to increase the capacity of existing structures, but this approach not only paints non-conformity of the youth to existing structures as a problem; it also disregards young people’s ability to carve their own space and exist beyond the limits of the current structures. Moreover, this approach ignores the African context. Continent-wide, the inability of politicians to understand the youth, merged with their disregard for the context of the continent, is responsible for socio-economic stagnation and misdirected policies that youth cannot relate to, although the same politicians claim to be working in our favour.

While there has been significant progress on the continent, according to a 2014 study by the African Development Bank, half of the continent experienced major protests in 2016, as Ismail Akwei points out in an article written the same year. The present context of Africa is one of widespread youth unemployment, rising corruption, according to a 2015 report by Transparency International, and greedy political leaders with very little accountability refusing to relinquish power. This has appeared to be the case even in countries such as South Africa that were exemplary in the past, as Khadija Patel argues in a 2013 article.

Looking specifically at the southern African regional context:

• Democracy in most countries has largely been instrumental rather than substantive, with limited citizen participation;

• There has been a failure to bring about meaningful change, despite regular elections;

• The region still faces elevated levels of food insecurity, unemployment, extreme poverty and inequality;

• There has been a failure to diversify the economy, which remains centred around resource extraction;

• Most people have informal livelihoods, presenting limited options for economic growth in rural areas;

• A failure to establish participatory institutions leaves power centralised around the presidency, and poor systems of transparency and accountability erode effective checks and balances, so communities are excluded from taking part in decisions that have a serious impact on their lives;

Endemic corruption and ineffective frameworks to fight corruption;

Violent crackdowns by state machinery on populations who express their objections to ongoing exclusion and deprivation;

Some countries have weak constitutional and legal structures that are unable to defend and foster human rights and the rule of law, or to safeguard access to justice for all citizens, and especially marginalised communities.

How can we expect the youth to thrive in such a toxic environment with dysfunctional structures? In the current political landscape, a non-conforming and disruptive youth is not a curse that will make matters worse, but rather a blessing that will challenge the status quo. This can only be done by a generation that thinks outside and beyond the existing structures.

Looking at it from this perspective, and in its proper context, this provides us with more appreciation for what are often portrayed as inherent flaws in the youth, but which are instead resistance strategies. We need young people who are unwilling to conform to the madness of the status quo. This is the only way that it can be challenged, resulting in real change for the continent.

When students in South Africa question the very nature of knowledge by calling for the “decolonisation” of universities, it is a sign that they are feeling alienated and oppressed by the existing structures and cannot thrive in such an environment. This also applies to the appeals for university fees to fall, as it communicates the sentiment and realities of the struggle that youth encounter in trying to gain access to education. Why are they being silenced when voicing these issues? The use of drastic means of expression by young people should be taken as a wake-up call to break the continuous structural cycle that links education and poverty, and limits the capacity for development. In such a chaotic environment, young people being disruptive and non-conformist is far from an anomaly; it is evidence of their sanity. We should rather be questioning the conformist mentality.

In the face of such developments, those who populate the offices of the continent’s major institutions respond by shutting down youth opinion, labelling it as disruptive and as just an excuse for their inability to conform to the social order. The increase in political consciousness among young people is the most significant advantage we hold, and our chance to sway things our way. Across the continent, recent years have seen young people taking the initiative and demanding accountability and good governance from their leaders. This has sometimes brought about unexpected results.

An example is the Burkinabé Revolution of 2014 in Burkina Faso, the initiative of a youth movement called Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen’s Broom) to oppose a constitutional change that would have extended Blaise Compaoré’s rule of 27 years. This resulted in his resignation and exile to Côte d’Ivoire.

Just a few years before, Senegalese youth movement group Y’en a Marre (Fed Up) initiated a campaign to register youth to vote in an effort to oppose ineffective government. The campaign led to the ousting of President Abdoulaye Wade and ended his bid for a third term in office. Similar trends have been seen in Gambia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Gabon, Burundi and elsewhere.

Southern Africa has not been exempt from disruptive youth uprisings. The Fees Must Fall and Decolonising Knowledge movements in South Africa were unique in their sudden surge out of nowhere and their informal nature. They are often referred to as “pop-up” movements, reinforcing the labelling of youth movements as disruptive and non-conforming. This is an important difference between these movements and those that emerged during the colonial and apartheid eras.

Partisanship characterised the older liberation movements to the extent that some of them became governing parties, and the interests of those countries and their people took a back seat to the interests of the party, as seen in the case of the ANC in South Africa and ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe. By contrast, the new youth movements clearly indicate their non-partisanship, and this is often reflected in voting patterns.

Research conducted by Afrobarometer in 36 African countries in 2016 found that just 65% of young people eligible to vote did so in their country’s previous national election, compared to 80% of older people. This is despite the surge in political protests by the youth. Political participation in the form of voting and engaging in civic activities remains low among those aged between 18 and 35.

This trend is observed globally. Key among the reasons cited for young people’s detachment from the overall political process is their unwillingness to associate themselves with partisan politics, and their distrust of current elected representatives. Youth protest often falls under the banner of civic and non-partisan groups, with the purpose of keeping politicians accountable, as explained by Idrissa Barry of Le Balai Citoyen, quoted in a 2017 article by Franck Kuwonu: “We are not politicians, we are citizens, and we don’t want to be beholden to political parties”. Yet, as Kuwonu points out, the non-partisan approach can also be problematic. While an anti-political approach might be a noble virtue, “by refusing to hold political office, young people appear to be denying themselves opportunities to participate in policymaking and changing the laws”.

A significant difference between the old and the new movements is in the nature and conception of leadership. Older movements were characterised by clearly defined hierarchy and a clear understanding of the roles of the leaders, which subsequently often turned into personality cults around particular leaders. The new movements promote a different understanding of leadership that focuses on the ideals of the movement, rather than its leaders. This is sometimes used to further the argument of those who see them as fundamentally non-conformist.

However, these new movements are not leaderless but “leaderful”; they exhibit the capacity to collectively lead, as with Lutte pour le Changement (Struggle for Change) (LUCHA) in the DRC, and this has helped them to avoid the trap of the “Big Man Syndrome” that characterised the older movements to the extent that it became an underlying part of them. Patrice Lumumba in the DRC, Nelson Mandela in South Africa, Sam Nujoma in Namibia and Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe all outshone the cause they were fighting for, bringing more focus onto themselves than the movement or the cause. As a result, some of the leaders who fought for African independence ended up as dictators and refused to relinquish power. This is one pattern that young people are refusing to conform to.

While the “informal” and “pop-up” nature of the new movements is often seen as a disadvantage, they have shown a capacity to mobilise people using social media with ease and rapidity. Concerns, however, remain about their capability to sustain momentum and transform causes shared on social networks to real, long-term changes on the ground. I have argued here that increasing political consciousness among the youth in Africa has seen young people expressing their voices in the public and private spheres. The youth have come to understand that the personal is political. I have also argued that the associated disruption and non-conformity can be seen as proof of their sanity rather than the opposite.

However, the question remains: how successful has this approach been? Many young Africans believe in non-partisanship, and do not see the existing political and socio-economic structures as a viable option. Should we really equate politics with partisanship? Should we leave government in the hands of the very political elites and parties we are fighting against?

While detachment from the political process is justifiable to the extent that non-participation is a refusal to perpetuate the continued existence of oppressive structures, we should acknowledge the dangers of this principled approach. Our unwillingness to take part in government and political office costs us opportunities. By depriving ourselves of a voice where it really matters, we are restricting our access to the spheres where decisions are made on policies and laws.

If we believe that there is a need for a change in leadership, a change that would best reflect the needs of young people, then who better than those in need of change to bring about the change? Who better than young people themselves to understand their own challenges and fix them? While it is acknowledged that youth are indeed taking steps in this direction, perhaps it is time to challenge ourselves to go further than “disruptive” protests.

Those who desire and seek to contribute to youth need to recognise how crucial and decisive is this moment in which we live. It provides opportunities to break a self-perpetuating cycle of the disenchanted joining the ranks and structures of the corrupt. The timing of the responses to youth concerns is crucial.

If such campaigns arouse no interest, young people could become disenchanted with the prospects for change. It is often said that young people are the future leaders of tomorrow. What many, including young people themselves, sometimes miss in this kind of narrative is the idea that young people are also leaders of today.

Reprinted with permission of the author, this is a shorter version of an article from Buwa! A Journal on African Women’s Experiences. Youth in Africa: Dominant & Counter Narratives, 8 December 2017.

NATHAN MUKOMA is a youth activist, writer and Congolese citizen living in South Africa. He is a lead organiser of StandWithCongo and is currently doing an internship at OSISA under the Democracy and Governance cluster. He holds a bachelor degree in social sciences (majoring in International Studies and Criminology) and is due to complete his honours degree in the same field. He is interested in issues of democracy and governance in Africa (and southern Africa specifically).