Book review

Book review

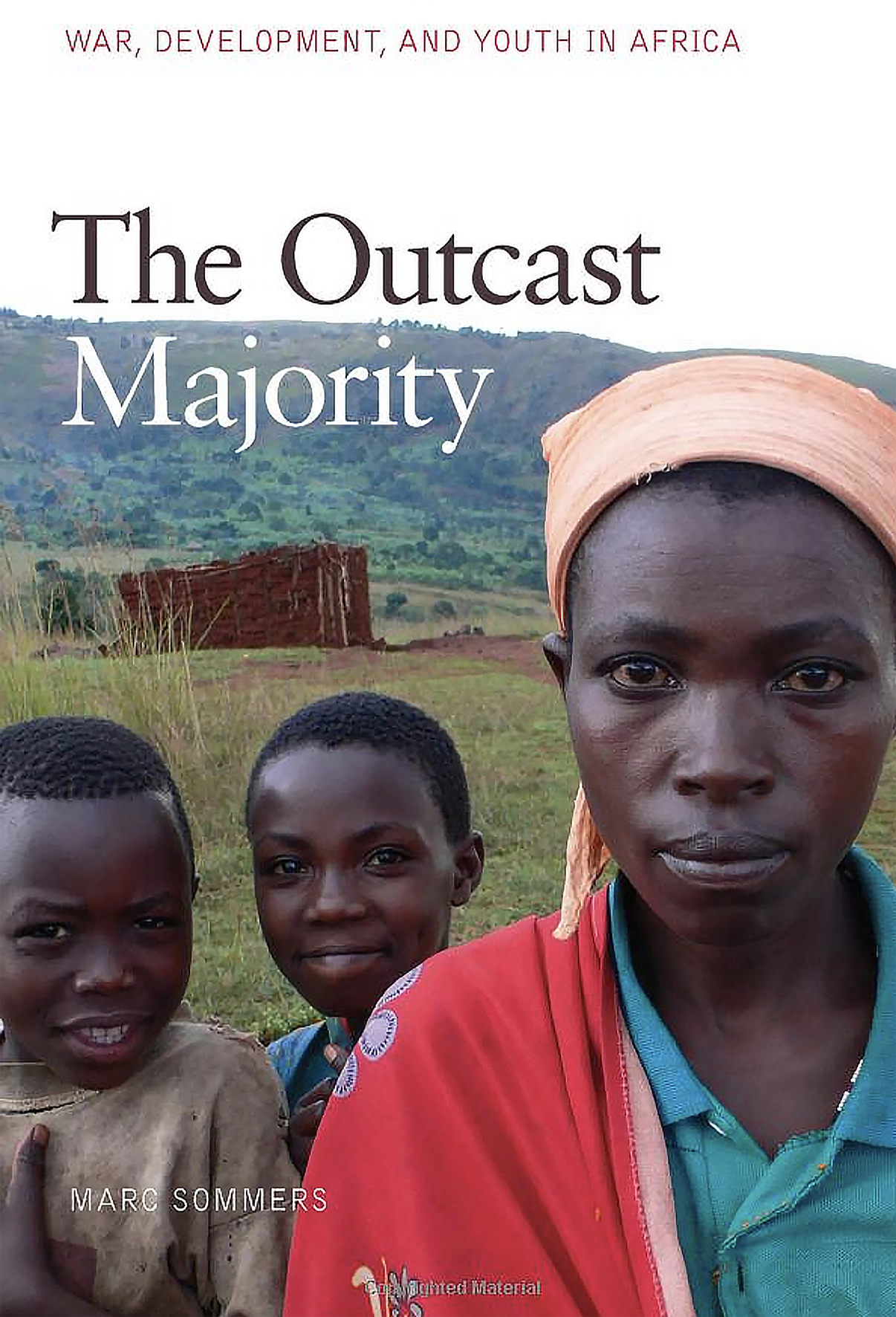

The Outcast Majority: War, Development, and Youth in Africa by Marc Sommers, University of Georgia Press, 2015

In recent decades, a number of African countries have been wracked by war, among them Sierra Leone, Liberia, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). And in all of them, young people, and young males especially, have become almost a reviled species, with theories linking the “youth bulge” to political instability and the threat of violence.

With this as a starting point, Marc Sommers’ book takes us on a startling exploration of the dysfunctional relationship between youth who have been through wars in Africa and the development agencies established to minister to them. In outline, Sommers argues that these young people are being marginalised by communities, governments, and international development and donor agencies. They have, he says, been “cast out”.

The development agencies do not appear to understand the youth they are supposed to try and help, argues Sommers, who has worked as a technical advisor to “numerous donor and UN agencies, policy institutes and NGOs”, according to his LinkedIn profile. The agencies don’t ask young people about their lives and living conditions – and when they do speak they don’t believe them. Even when they do ask them about their lives, they pose the wrong questions in the wrong way, he argues.

It is the continent’s warlords who have recognised the potential of young people, often putting them in positions of responsibility and trust, with leadership tasks, he argues. Somewhat ironically, he suggests, the international donor community in particular needs to learn from the warlords. This counter-intuitive approach runs throughout the book, in which Sommers disabuses us of myriad misconceptions and sheds light on the real situation of many of Africa’s young people.

The book begins with the facts: how “war affects the lives, trajectories and bodies of youth”. Most young Africans will never progress beyond primary school because they face a clash of values and priorities. In particular, older children often have to work to enable younger siblings to attend primary school. Young people in Africa can find themselves growing up in situations in which the future is absent, and where survival means adapting to horrific conditions.

During the Liberian civil war between 1989 and 2003, for instance, villages were destroyed and survivors were forced to take to the forests. Similarly, during the civil war in Sierra Leone from 1991 to 2002, citizens faced the brutal reign of Liberia’s marauding Revolutionary United Front, and were often subjected to amputation, rape (males and females) and abduction.

In South Sudan, from the mid-1980s to 2002, villagers were forced to put up with regular invasions that saw them living under militias that violated their rights – only to be faced by stronger militias the next time around that punished them for obeying the departing militia. Those who moved to other villages were suspected of being spies or members of resistance organisations, and killed. During the Rwandan genocide of 1994, sexual violence was used as a weapon of subjugation, as it has been elsewhere – including eastern Europe. Young girls were raped in front of parents, and siblings forced to rape sisters and even mothers.

In such circumstances many young people could only escape their plight by becoming members of militias themselves, which at least enabled them to survive by looting. In Liberia, Charles Taylor practised a “pay yourself” policy – “if you don’t loot you don’t eat”. During times of war, youth combatants who had not been used to having money suddenly had access to cars, beer and women. They had “become someone” and escaped insignificance. Girl combatants suffered unrelenting victimisation, as well as profound invisibility, during and after combat.

Sommers reviews various theories of trauma for their relevance to the African situation, which poses challenges to standard theories. For example, post-traumatic stress theory assumes a relative stability before an experience of trauma, but the African child will often have been imbricated in a traumatic situation from the start of life, and will have received constant, repetitive psychic pounding before the emergence of a large-scale conflict in their society.

This makes the application of such theories problematic, Sommers suggests. Traumatised African youth often cannot be counselled. Their survival is based not on talking, but on active forgetting. As Sommers suggests, prohibitions on talk are rational when talk can only reproduce memories of war and their associated paralysis of the will. So it is that researchers remain in the dark and underestimate their subjects’ suffering.

Sommers rounds off his account of the effects of war by showing how young Africans are often doomed to remain in the category of youth. Normally, adulthood would require such things as having a job, being able to buy a house and support children and their education. Because they are held back from these things, their adulthood may be permanently deferred, and they will find themselves living in limbo. The effects of war will mar post-war situations. Adults have expectations of youth that are totally out of touch with their experiences. Young people, meanwhile, are still suffering from the effects of sexual violence, abduction and alienation from each other as well as their parents. And so they migrate to cities.

Development agencies tout agriculture as the answer to Africa’s lack of jobs, but many alienated African youths experience the city as a place of freedom: from overbearing traditions, from adults, from rules of marriage that demand adult status. In villages, farm work is considered menial, a female preserve, and is subject to constant humiliation. The city, meanwhile, is seen as a place of excitement, innovation, and liberating anonymity.

Development programmes often exacerbate tensions where they operate, Sommers goes on. Selecting some young people, usually those with elite backgrounds, they exclude “bad youth” – who then perceive such programmes mainly as a source of exclusion. The NGOs that operate in their environments also reflect the affluent lifestyles of NGO workers, creating desires in the youth that will be frustrated and result in resentment, the author says.

Turning to the work of the UN, World Bank, USAID and other development agencies in post-war situations, Sommers argues that these are out of touch with the experiences of youth. They are, moreover, he says, subject to the delusion that they are clocking up successes while societies disintegrate around them.

Rwanda is often touted as an example of a successful transition from war, but the flipside of this is that the country’s population has been subjugated by an authoritarian regime. The country’s economic success, according to many reports, derives from raids on mineral resources in eastern DRC, where the Rwandan army has been accused of atrocities. From 1994 to 2003, as many as 300,000 Hutus were killed in the DRC, and up to 90,000 dissenters in Rwanda itself.

But development agencies sidestep these realities, Sommers says. Their “success literature” is based on quantitative research that is motivated by the need to show that neo-liberal programmes are working, and so fixes on specific indices to demonstrate improvements. He argues that this literature betrays a simplistic view that favours elite youth and farm workers at the expense of the impoverished and alienated young people of the cities.

No raving leftie, Sommers nevertheless places the blame for the current situation on the neo-liberalism of the World Bank and allied institutions. In particular, he blames the methods they use, which were formulated by Robert McNamara, who was US Secretary of Defence from 1961-1968, before becoming World Bank president in 1968. At the Pentagon, he applied corporate methods – measurement based decision-making and policy analysis – which he also took to the World Bank.

Sommers lists five consequences of quantitative measurement: emphasis on compliance with agency regulations, which results in a subtle redefinition of development and a focus on short-term goals; a cost-benefit approach advocated by development economics; the measurement of activities, outputs, purposes and goals, influenced by a (US global think tank with which McNamara was associated) RAND-style Logical Framework approach; a focus on quantifiable results and hard-science programmes in areas such as public health, which have measurable outcomes popular with the media; and a heavy emphasis on the provision of measurable public-service delivery, while institutions such as education are ignored.

It was this kind of thinking that went into the IMF’s notorious structural adjustment programmes in the last decades of the 20th century, Sommers argues. First put into operation in Senegal in 1979, their claimed purpose was to forge lean governments and large private sectors and so fuel trade and growth. However, their real effect was to open up (so-called) third world economies to global markets. On this, Sommers quotes Joseph Stiglitz: “privatisation in transition countries led to asset stripping rather than wealth creation”.

Sommers is especially scathing of a programme devised by Jeffrey Sachs, who launched the Millennium Villages Project (MVP) in line with the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, as a supposed “scientific approach to ending poverty”. Sachs focused on a region in Kenya, where villages were chosen for targeted investment, so that “disease can be controlled, crop yields increased, and infrastructure such as roads taken to villages”. Yet, after the UN invested $2.5m in Dertu, Kenya, neighbours clashed, clans tried to control the money, and rampant inequality emerged.

Critics of Sachs noted that these projects were evaluated by project members and presented as successes. More generally, Sommers argues, this tendency to self-evaluate – incorrectly and dishonestly – has been one of the downsides of developmental initiatives more widely, ultimately serving agency staff and not their subjects.

Sommers closes his book with a set of recommendations for developmental agencies which would bring them in line with their purported aims. He calls on agencies to include young people in the design and operation of their programmes. The priorities of so-called “bad youth” must be addressed, as this is the group that most needs help and their inclusion would reverse negative patterns. The favouring of elite youth makes a mockery of development, he insists.

Further, he exhorts agencies to forego previous methods and develop a sensitivity to the peculiarities of the youth – their differences (class, gender, experience) – and, above all, to listen to them, especially the excluded. He also urges agencies to oppose government abuses, because the effectiveness of the agencies’ programmes depends on their credibility in opposing human rights abuses. Many agencies have played along with or ignored state outrages, as in Rwanda.

Quantitative research, Sommers insists, must be integrated into qualitative data to achieve a balance between short-term and long-term goals. Qualitative research must include insights from a range of disciplines as well as engagements with youth that will inspire trust from them. A passionate but rigorous defender of Africa’s young people, Sommers’ insights need to be heeded if the continent is to emerge from its quagmire.

Yunus Momoniat is a researcher and writer at South African History Online and an occasional political commentator.