In 2016, an opposition Member of Parliament in Botswana, Pius Mokgware, a former army general, warned that youth unemployment was a ticking time bomb. His greatest fear was that discontent about unemployment could lead young people to divert their energies to criminal and terrorist activities, which could leave the country vulnerable to terrorist organisations such as Boko Haram, Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab.

“We have IT graduates who lead the pack of unemployed graduates. These people can be recruited by terrorists to develop software and viruses to hack our computers, destabilise water and electricity systems and destroy this country in the blink of an eye,” Mokgware warned.

We could dismiss Mokgware’s concern as fantastical, given Botswana’s dominant narrative, which projects a positive image of the country as well positioned on international indices of governance, peace and prosperity. But behind this fairytale lies a little-known history of youth activism in the country, inspired by festering frustration about unemployment, inequality, injustice and corruption.

In April 2017, a youth group calling itself The Unemployment Movement was harassed and arrested by the Botswana Police. A year before that a number of people had been beaten, arrested and detained by the police for staging a peaceful protest outside parliament against unemployment.

Some 23 years before this, on 16 February 1995, University of Botswana (UB) students in the country’s capital, Gaborone, took part in riots that shook the country. School pupils from Radikolo Junior Secondary School in Mochudi had started those riots a few weeks earlier, following the November 1994 death of 14-year-old, Segametsi Mogomotsi, who was apparently killed in a ritual murder.

“We went to the National Assembly to demand answers from legislators who were in a session at the time,” Nelson Ramaotwana, who won a council seat in the 1999 general election while still a University of Botswana student and SRC president, told Africa in Fact.

“Pushing open the door to the parliament chambers, we were greeted by teargas. Everyone had to run, as the riot police were coming at us with the utmost aggression.” Ramaotwana recalls that at one point the police threatened to use live bullets on the students. “That was when a lot of our leaders got arrested and the protest was stopped.”

The Segametsi Mogomotsi riots were a major event in Botswana and seminal for youth activism in the country. “Nothing of the kind had happened before, and the people themselves were surprised – indeed, in a state of shock,” wrote Ørnulf Gulbrandsen in The Discourse of ‘Ritual Murder’: Popular Reactions to Political Leaders in Botswana in 2002. “The peaceful, harmonious order of political life in Botswana, an idealisation no doubt, seemed to them to have been completely shattered.”

More than 200 students were arrested between January and February 1995. Binto Moroke, who was in his early 20s, was shot dead by an officer of the country’s paramilitary Botswana Police unit, the Special Support Group (SSG). Fifteen protesters were treated for rubber-bullet wounds, while one passerby, who had not been part of the protests, was shot and paralysed. The Botswana government’s handling of the riots brought it a new notoriety for suppressing dissent. The main opposition party, the Botswana National Front, accused the government of running “a police state”, while Amnesty International expressed concern about the developments.

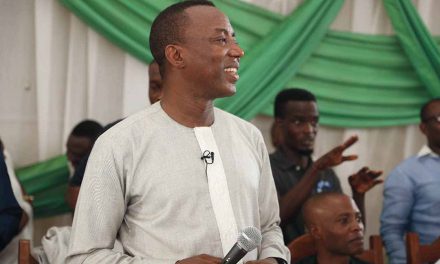

Khumoekae Richard, a former University of Botswana SRC and Botswana National Front Youth League president, emerged as a student activist when students supported a 2011 strike in which civil servants were demanding a 16% salary increase. “At that time, the public service needed encouragement – especially given that the country was ruled by a military trained despot and a feared man (former president Ian Khama),” he told Africa in Fact. Richard, the author of two books focusing on politics and democracy, is currently doing postgraduate studies at Simon Fraser University in Canada.

Like the 1995 protests, the 2011 strike was a major event nationally. Dubbed “the mother of all strikes”, it drew the attention of international media. US broadcaster CNN estimated that around 93,000 of the country’s 103,000 government workers downed tools. University of Botswana students, already notorious for their activism, were soon joined by school students, some as young as 12 years old, at Moruakgomo Community Junior Secondary School in Molepolole (about 60 km west of Gaborone). The aim was to present a petition to the authorities stating their grievances over deteriorating learning conditions caused by the strike.

The young school students confronted riot police, pelting them with rocks and sending them scattering in a mall in the village. The confrontation lasted at least an hour, and the police had to bring in reinforcements that included armour-plated riot vehicles and a helicopter. The police also resorted to rubber bullets and tear gas. At least six police officers were rushed to hospital, while six students also sustained rubber-bullet injuries.

Last year, the state used violence against Unemployment Movement protesters, who were beaten with apartheid-era whips known as sjamboks. Originally used to drive oxen, sjamboks gained notoriety in South Africa for their use by white police officers during riots. Richard says that the Botswana government “understands the role of youth activism in a democracy” but represses it because it fears dissent could spread among its citizens.

Some are concerned, however, that student activism may be losing focus and momentum. Ramaotwana is one critic of the new generation of student activists: he says the current generation are only interested in protesting for increments of student allowances.

“During our time, we did political education. We knew what capitalism and communism meant, and we studied their effects on reality. Moreover, we were aware that we were the professionals of tomorrow,” he says. “We protested against corruption and injustice because we had a nationwide view of things.”

Moagi Ntisapa, an SRC member at Limkokwing University, a private university in Gaborone, believes university management is “killing” student activism because, like government, it fears dissent. At Limkokwing, SRC elections are no longer allowed, with university management imposing representatives, Ntisapa says. But a former leader of the National Student Union, Thato Ntwaetsile, says that current student leaders “are either sell-outs or are just too faint-hearted for the job”.

Former president Ian Khama

Illustration: Vusi Malindi

But young Botswanans in general aren’t turning their backs on politics (Indeed, Botswana’s new president, Mokgweetsi Masisi, appointed a 31-year-old economist, Bogolo Kenewendo, as his investment, trade and industry minister in April this year). The reason? According to the World Bank (2017), youth unemployment in Botswana stands at 33.2%.

The 2014 general election saw a record when some 352,579 youth registered to vote, a trend expected to be replicated in the 2019 elections – to the benefit of opposition parties as youth disillusionment with the status quo continues to grow. It is particularly apparent on social media, where the country’s young people are vocal about their economic situation.

In an angry Facebook comment that received 938 likes and 120 replies, a youth, Tumelo Lepere, responded to a post by former president Ian Khama by writing: “You were the worst president we have had, the only thing I remember with your rule is corruption and high unemployment.”

Lepere’s comment was one of many in which young people listed grievances against government failures. Some, however, did express optimism about Masisi. But, of course, time will tell, as it always does.

OTENG CHILUME is an experienced journalist who began his career as a broadcaster in 2010 with Duma FM, Botswana’s most listened to private radio station. He has also worked for Yarona FM, a national youth radio station, as head of news and currently works for The Botswana Gazette newspaper as a chief sub editor.