September 2024 marks exactly 39 years since the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women that culminated in the Beijing Declaration and the Platform for Action. This conference heralded a critical turning point for the global agenda for gender equality, and had the girl child among its 12 critical areas of concern.

However, the African girl child, even in 2024, continues the struggle for even the smallest wins in economic and social equality, handicapped by complex challenges rooted in cultural, social, economic and institutional practices and norms.

Africa is home to about 308 million young women and girls. The challenges they face begin very early in life, with a lack of access to education.

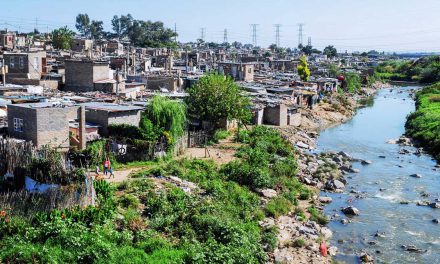

Young girls wash clothes at a cleaning point in the Korsi refugee camp in Birao on August 10, 2024. Over 80% of the camp residents are women and children who fled war in Darfur. Photo by Amaury Falt-Brown/AFP

In sub-Saharan Africa, nine million girls aged six to 11 are out of school, compared to six million boys, according to UNESCO’s submission to the AU’s first Pan-African Conference on Girls’ and Women’s Education in July, with girls in conflict-affected areas 2.5 times more likely to be out of school than boys.

“Gender parity has not been achieved at any education level in the region, with disparities persisting across primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary levels,” UNESCO stated at the conference.

Exacerbating this situation is School-Related Gender-Based Violence (SRGBV), one of the most common forms of GBV. “Unfortunately, SRGBV has very serious negative effects on female students’ lives, such as grief or depression, low self-esteem, early and unwanted pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS,” stated the African Union High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies in a 2023 blog.

Menstruation is another cause of school absenteeism for adolescent girls. In South Africa (SA), 7 million girls are reported absent from school every month due to a lack of sanitary pads, which results in them missing 25% of learning during the school year, according to the SA Journal of Child Health in 2022.

This situation carries significant economic implications. UNESCO research shows that by 2030, the economic losses to Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP due to girls not learning amount to US$210 billion (and US$190 billion for boys).

Child marriage, a violation of human rights which can have severe physical and emotional consequences, also persists, with about 41% of girls marrying before reaching the age of 18, according to UNICEF.

The highest incidence of child marriage is in West and Central Africa. Niger, for example, has a long tradition of child marriage. “A lack of education among Nigerien girls is both a cause and consequence of child marriages. Girls who get married are usually forced to drop out of school due to events such as early childbearing, and those who have no education ultimately have little option but to marry very young,” wrote Monique Bennett in GGA’s Africa in Fact October 2022 edition, themed on the Girl Child.

Teenage pregnancy, meanwhile, has a prevalence rate of more than 25% in 24 African countries, a rate that reaches as high as 48% in Niger, 44% in Chad, and 43% in Equatorial Guinea, according to a study by the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, titled Teenage Pregnancy in Africa: Status, Progress and Challenges (2022).

Underpinning this complex matrix of obstacles facing an African girl child are traditional, patriarchal systems – embedded in many African cultures – emphasising a girl’s domestic responsibilities over her education, especially in poor communities where resources are limited.

And while many African countries have policies aimed at promoting girls’ education and gender equality, the enforcement of these laws is often weak, and support systems to help girls overcome these barriers are inadequate.

GGA’s Sikhululekile Mashingaidze and Mass Public Opinion’s Simangele Moyo-Nyede discovered, during interviews for GGA’s AIF Girl Child edition in 2022, that in spite of Zimbabwe’s Amended Education Act of 2020 allowing re-entry for pregnant girls and adolescent mothers, a majority of schoolgirls who fall pregnant rarely return to school. This is largely because they are stigmatised, by both educators and society.

The disempowerment of African women, rooted in the dangers and prejudices they face as children, is itself a huge problem. In his Women’s Day speech in the Northern Cape last month, President Cyril Ramaphosa highlighted the alarming levels of GBV in South Africa, quoting Human Sciences Research Council statistics showing that 7% of women aged 18 and older (1.5 million) experience physical or sexual violence annually.

A total of 13% of women had suffered economic abuse by intimate partners, he continued, urging for more economic opportunities for women, “so they are less vulnerable to exploitation and abuse …We need to address the massive inequality in income between men and women,” he said. This is underscored in a new Catalytic Strategy gender pay gap report, released last month, showing 40% of households in South Africa are led by women with financial responsibility for their families, including extended families. Yet only 14% of women fall into the category of ‘top earners’.

In 2021, UNICEF published the Gender Action Plan (2021–2030), with recommendations on how to tackle gender inequality. Among other critical issues, the Gender Action Plan advocates for maternal health and nutrition, including HIV testing, prevention, counselling and care; ending harmful practices (child marriage and female genital mutilation) and violence against girls, boys and women; ensuring girls have access to water, sanitation and hygiene systems, including services for menstrual health; and promoting gender-responsive social protection and care, including through the enforcement of laws. This underscores the centrality of gender-responsive education systems, especially when it comes to equitable access to schooling, STEM subjects, and digital skills for adolescent girls.

The world of employment is another area where young women experience disempowerment, in the form of the gender and pay gap. The International Labour Organisation reveals that women who want to work face more constraints in securing a job than men, with the current global labour force participation rate for women just under 47% compared to 72% for men (2022).

Addressing these issues requires coordinated efforts by the public and private sectors, along with NGOs, to improve access to education, create safe and supportive learning environments for girls, and promote gender equality in the workplace, socially, and in their communities. Empowering the girl child not only uplifts individuals, by being educated and economically active, young women help build more stable and equitable societies, which in turn improves social cohesion and reduces crime and violence.

AFRICA’S GIRL CHILD DIALOGUES

GGA has been involved in advocacy for the girl child for three years, through its annual Africa’s Girl Child Dialogues. This is a day-long conference, with partner sponsorship that enables the girls’ exposure to various career opportunities for young women.

Last year (2023) GGA partnered with Anglo-American, and the focus was on careers in mining, ICT and wildlife. This year, the Girl Child Dialogues, in partnership with Boston City Campus, will focus on career opportunities in the media and publications sector. Girls in Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria and Zimbabwe will be participating virtually through these GGA country centres and their partners. Scheduled annually on the International Day of the Girl, Africa’s Girl Child Dialogue’s continental reach is growing each year.

This year’s event takes place on 11 October 2024, at Boston City Campus. (See opposite advert). To read our Africa in Fact edition on the Girl Child, published in October 2022, click here.

This article first appeared in Mail & Guardian.