The 2022 National Assembly Elections were the tenth since independence in 1966. They were regulated by the Constitution of Lesotho of 1993, as amended. In addition to the Constitution, the elections were governed by the National Assembly Electoral Act of 2011 and the Electoral Code of Conduct.

Lesotho Revolution for Prosperity party (RFP) leader Sam Matekane meets his supporters after he announced an alliance with the Alliance of Democrats (AD) and the Movement for Economic Change (MEC) in Maseru on October 11, 2022. Photo: MOLISE MOLISE/AFP

On 7 October 2022, Lesotho held the General Assembly elections. In every election in the country, there are many visible trends, but this article focuses on four of these:

- Proliferation of political parties

- Similar manifestos

- Employment of election observers

- Post-election destabilisation

Reasons for the proliferation of political parties

The country saw the establishment of new political parties before October 2022 elections, to the extent that Commissioner Tsoeu Petlane commented that looking at the rate at which political parties were registering, there was a possibility that Lesotho could have 100 parties by the time of the 2022 elections. The number ended up at 65. Factors contributing to the proliferation of political parties include: the benefits to politicians that comes with being in government such as perks of a monthly salary of M37,000 (likely to increase post-2022 elections); interest-free loans of M500,000; ability to influence the awarding of lucrative government tenders and awarding themselves M5,000 to bury the dead in their constituencies.

Political parties registered with the Independent Election Commission (IEC) of Lesotho were entitled to funding from the Consolidated Fund for campaigning and payment of party agents. Conversely, latent parties become a burden to the IEC as they do not perform the intended task with the fund, instead, some leaders used it for personal gains and there is no legal recourse or accountability. More often than not, political parties mushroomed because of politics of the stomach. Many want wealth, and food for their families, not necessarily for national welfare. This became evident at the high levels of corruption among the politicians including the contest for tenders.

Many of these political parties mushroom towards the elections. For example, in the 1965 and 1970 elections only three political parties were contested, namely: Basutoland Congress Party (BCP), the Basotho National Party (BNP), and the Marematlou Freedom Party (MFP) and since then parties have increased exponentially. In 1993, 12 political parties contested; in 1998 they increased to 13; in 2002 they skyrocketed to 19; in 2007 they stood at 15; in 2012, there were 18; 23 parties contested in 2015; 29 took part in 2017, and 2022 saw the highest number at 65 parties. Out of 65 political parties contesting the 2022 elections, only 11 parties were led by women. Some scholars commended the proliferation of political parties in the country as rooting of democracy while others counter-argued that it is all about the politics of the stomach.

The threshold for registering political parties also provides conducive conditions for the proliferation of political parties. Each party requires five hundred signatures and the IEC cannot verify the authenticity of the signatures. The intolerance within the political party leadership led to party splits, hence many breakaway parties. For example, the Empowerment Movement for Basotho (EMB) was formed by disgruntled All Basotho Convention (ABC) stalwarts, led by Katiso Phasumane and Futho Hoohlo. They abhorred the unending infighting within the ABC. Nqosa Mahao and Tefo Mapesela left the ABC and formed the Basotho Action Party and Basotho Patriotic Party (BPP) respectively. The Speaker of the National Assembly, Sephiri Motanyane, said the formation of new political parties exercises a democratic right as Lesotho is a democratic country, in response to a concern raised by former Member of Parliament, Likeleli Tampane, objecting to the proliferation of so many political parties for 2022 elections.

Manifestos of political parties during 2022 elections

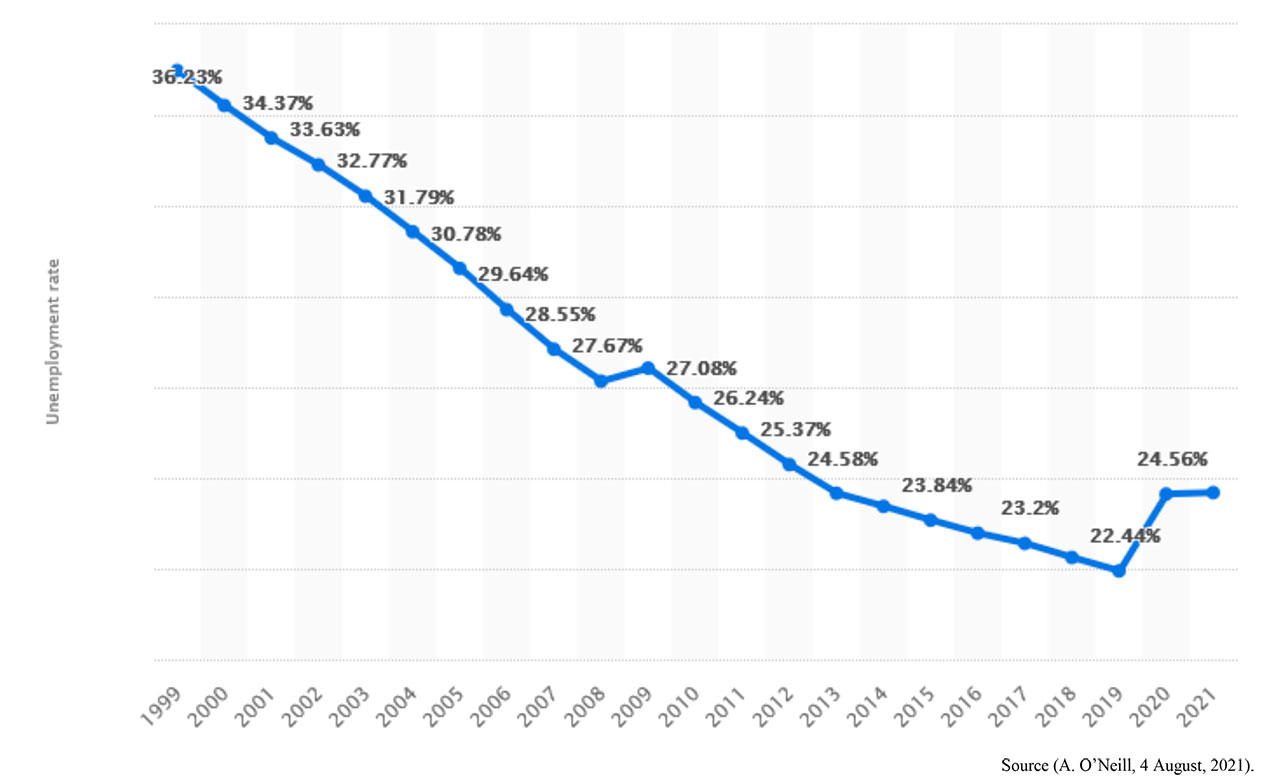

Most political parties almost had the same manifestos in different words to an extent that the BAP accused the RFP of stealing their ideas on reviving the economy. They all promised to fight unemployment, create jobs, fight corruption, improving the economy of the country. The majority of these parties did not provide the mechanisms and how they would improve the lives of the masses of poor and unemployed youth. The unemployment rate has been above 20% since 1999. Table A below attests to this reality:

Table A: Youth Unemployment rate in Lesotho from 1999-2021

The manifestos and the number of contesting parties confirm what Likoti (2021, 166) observed:

“These parties only differ in names and colour. Party manifestos are the same. The

the difference is only in the language used in writing the manifesto and leadership.”

This is true of many political parties contesting the 2022 elections in the country because their manifestos relied entirely on the bigger parties.

Election observers

The IEC invited both local and international observers. The prime role of the observer missions is to ensure the integrity of the elections. The international observers comprised: the European Union Election Observer Mission (EU-EOM) headed by Ignazio Corrao – Chief Observer and a Member of the European Parliament from Italy; the Commonwealth also accepted the invitation and members arrived in the country on the 29 September 2022 headed by Danny Faure, former president of Seychelles; the SADC Election Observer Mission (SEOM) headed by Honourable Frans Kapofi- Minister of Defence and Veterans Affairs of Namibia had deployed 62 observers from 11 SADC countries: Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe; African Union Election Observer Mission (AUEOM) led by H.E Dr. Speciosa Wandira Kazibwe, former Vice President of the Republic of Uganda has arrived in Maseru on 3rd October 2022; and the Electoral Commissions Forum of SADC Countries (ECF-SADC) was led by Denis Kadima, Chairperson of the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

They interacted with various stakeholders to ensure the level of preparedness and a conducive environment for free and fair elections in the country. In their preliminary statements, they commended Lesotho stakeholders for the peaceful pre-election period including campaigns, voting, counting of the ballots, and the announcement thereto. They all encouraged the 11th parliament to complete the reform process and address the voter’s roll as many stakeholders had expressed concerns. They witnessed the process as it unfolded first hand and they confirmed this in their preliminary statements.

History of post-election destabilisation

Going by the history of elections in Lesotho, the pre-election period is generally peaceful and calm. The instability often starts after the elections or during the sitting of parliament. Since the adaption of the Mixed Member Proportion (MMP) model, hung parliaments became a feature of Lesotho politics with no political party reaching the magic number of 60+1. Consequently, the coalition governments were formed in the 2012, 2015, and 2017 snap elections. The first three coalition governments did not complete their five-year tenure. The grand coalition ended its tenure because of the resoluteness of DC, which did not entertain the infighting within the ABC that passed endless motions of no confidence in Prime Minister Moeketsi Majoro, especially after he defied the recall by the party. Therefore, a few factors that may disturb the October 2022 pre-election peace and calmness are the following:

- The use of the old constitution under which the 2022 National Assembly elections were held might be exploited by some politicians to create instability in the country. Politicians always look for constitutional loopholes to pursue their selfish ends. The constitutional reforms aimed at curbing causes of election instability were not completed.

- The problematic voters roll. Some political parties and ordinary citizens complained that it contained inaccuracies, and duplicates and was riddled with egregious errors which could have a significant bearing on the outcomes of the elections. The voters’ roll is the cornerstone of the elections as it contains the particulars of the voters and their eligibility to vote. If it creates doubts in political parties before elections, it may be difficult to accept the outcomes of such a process. The IEC has however disputed the allegations and threatened legal action against those spreading misinformation;

- Some political parties such as ABC, DC, and MEC are being supported and financed by Famo Music Groups (FMGs). There are two major FMGs in the country: Terene Famo Music Group (TFMG) and Seakhi Famo Music Group (SFMG). These FMGs have syndicates that engage in a variety of illegal activities such as robberies, murders, and illegal mining in South Africa. TFMG supports the ABC and the DC. The MEC is supported by the SFMG and leaders of these political parties protect them from prosecution after being detained after committing a crime. However, there is a fear that these parties could use such groups to intimidate rival parties and create chaos when their parties do not perform well; and

- Some election observers such as the EU-EOM expressed concerns that the electoral Act sets long deadlines of 30 days for both submission and adjudication of election petitions. This timeline is against international good practice. Lesotho should have learned about the 2007 post-election petition lodged by the MFP on the allocation of the PR seats which took more than 30 days to resolve.

Towards the elections

On 21 July 2022, the political parties signed the Code of Conduct that among others, prohibited political leaders from involving the Lesotho Defence Force, the Lesotho Mounted Police Service, the National Security Service, and the Lesotho Correctional Service in their political activities.

On 30 September 2022, the country went for advanced voting of 3,000 registered voters. On 7 October 2022, about 1 387 861 registered voters (767,158 women and 616,868 men) queued to vote. Immediately after the voting stations closed, IEC and other stakeholders started counting the ballot papers and transmitted them to the Command Centre at Manthabiseng Convention Centre.

Election day and the outcomes

For the 2022 elections, there were 1 387 861 registered voters (767, 158 women, and 616,868 men), with an increase of 129 652 newly registered voters since the 2017 elections. There are 10 districts and 80 constituencies. There were 3, 151 voting stations across the country. The advanced voting took place on 30 September 2022 and 3000 had registered to vote. The voting took place on 7th October 2022. Voting stations opened at 7hrs and closed at 17 hours while others closed slightly later to accommodate voters who were in the queues already.

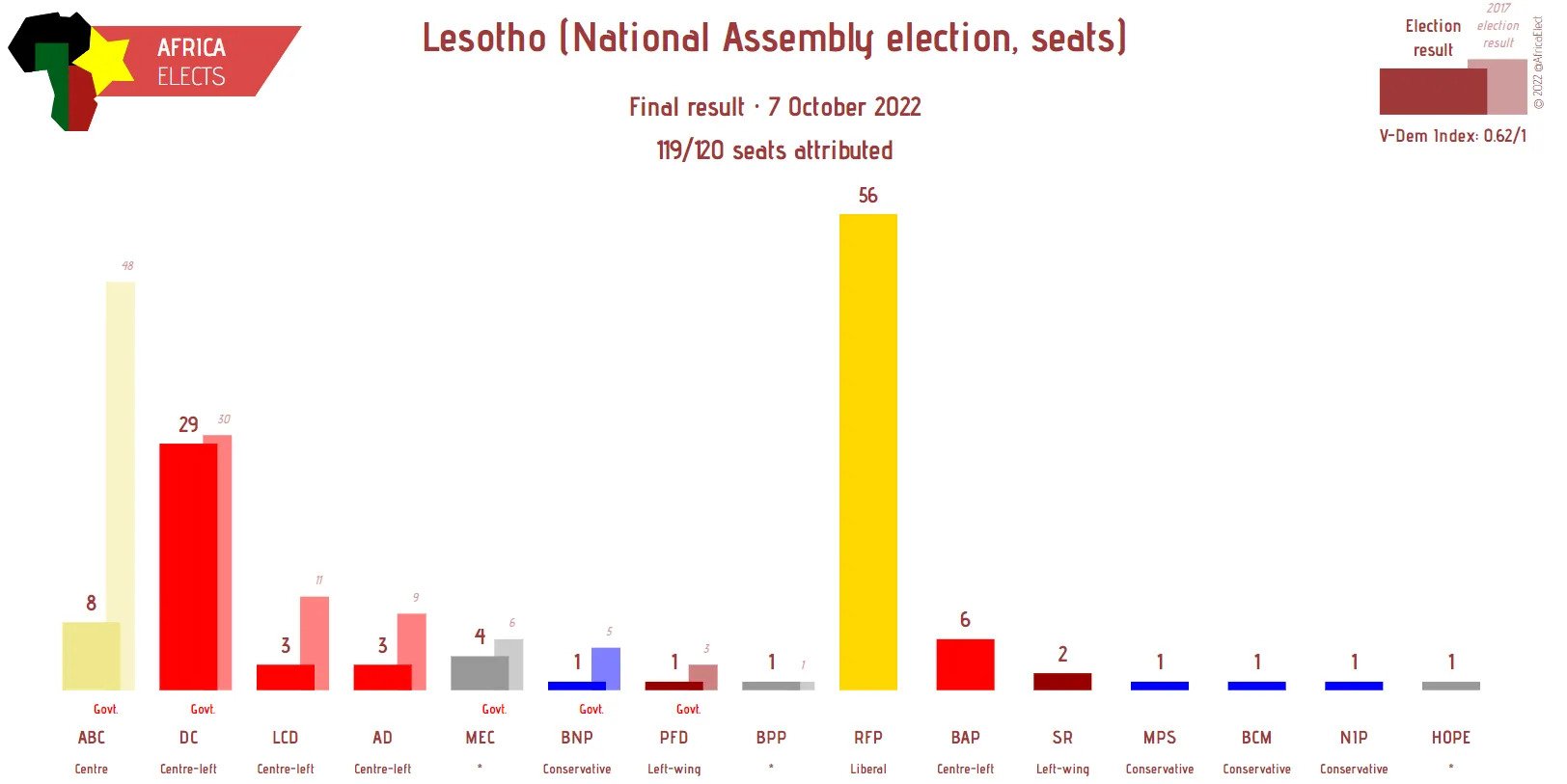

The overall elections outcomes were as follows:

Source: Africaelect.com/lesotho (10 October 2022)

Some political heavyweights in the country lost their constituencies. These included ABC leader, Nkaku Kabi; LCD leader Mothejoa Metsing; AD leader Monyane Moleleki (it was the first time he lost his constituency since 1993); Madichaba Lekhooa of UFC. The former First Lady ‘Maesiah Thabane also lost the Mokhotlong constituency. She got 190 votes while Adontsi Letsema (RFP) won with 2680 votes.

In the Likotsi-Maseru constituency, the RFP’s Itumeleng Rantsho beat two heavyweights, the former cabinet ministers Chalane Phori (ABC) and RCL leader Keketso Rantšo. The leader of DC, Mathibeli Mokhothu, was among the few that won, with 3606 votes against the RFP’s 1586. In the Mantsonyane 72 constituency, the leader of RFP amassed 4629 against his competitors, M. Maoshoa and R. Malieketso, who got 1048 and 239 respectively.

The youth have played a critical role in voting RFP into power in the 2022 elections. However, while efforts were made to encourage voter turnout, the voters were generally apathetic. This is attested to in the low turnout. There was a voter turnout of 51.86% in 2012, 2015 saw a dive of 46.61%, and also in 2017, the voter turnout was at 46.37%. In the 2022 national elections, voter turnout dropped to 37.71%.

On 11 October 2022, Matekane (RFP), Moleleki (AD) and Mochoboroane (MEC) signed a coalition agreement for Lesotho’s 11th Parliament with 65 seats, which is a slim majority. Moleleki rebuked those who despised Matekane for joining politics in April 2022. He went public that he made Matekane a millionaire, and he also cited others such as None None, Jimmi Lenka, Mohlomi Moleko, Thulo Thulo, and many others. He did not elaborate on how he made them rich tycoons. On the same day, Matekane said he chose the two parties because they share the same vision of cutting down on government expenditure and improving the delivery of government services to Lesotho’s population.

Matekane is a newcomer to politics but the leaders of the two partner parties bring experience in government. Moleleki served as deputy prime minister from June 2017 to May 2020 while Mochoboroane was development planning minister in the outgoing ABC-led government 2017-2022. Matekane said the coalition’s immediate tasks included “reining government expenditure, stabilising the economy, and uniting the nation”. Lesotho has been plagued by chronic instability and widespread poverty.

Going forward for stable Lesotho, the following are key to consider:

- Lesotho to develop anti-political party proliferation measures as part of the comprehensive reforms, and all the observer missions deployed to the country should urge the envisaged 11th parliament stakeholders to prioritise the reforms. Time frames should be set within which reforms should be completed.

- The political parties should develop succession policies. Some leaders overstay their welcome and end up treating political parties like their own property, which often worsens infighting, and power struggles and finally leads to splits which contribute to the proliferation of political parties.

- Political parties should shun corruption because it retards the country’s progress and service delivery. Those rooted in corruption are: “like scavengers, everything is done with the sole purpose of self-gradation. They eat everything from their prey until the bones are exposed and nothing is left. That is the nature and mindset of some politicians.”

- Lesotho needs peace for development. As Santho (2017, 128) opines, “Lesotho needs peace, security, good governance, and stability to realise inclusive growth and development”.

- SADC and the international community, in consultation with all Lesotho stakeholders, should set clear and strict time-frames for the completion of the reforms to end, once and for all, the instability in the country, as expressed in the country’s National Anthem.

“Molimo ak’u boloke Lesotho – May our God protect and preserve Lesotho.

U felise lintsoa le matsoenyeho – May all wars and quarrels pass away and go.

Le be le khotso – peace should dwell in thee.”

Lesotho Revolution for Prosperity party (RFP)’s supporters gather to greet their leader after he announced an alliance with the Alliance of Democrats (AD) and the Movement for Economic Change (MEC) in Maseru on October 11, 2022. Photo: MOLISE MOLISE/AFP

References:

Likoti, F (2021). “The impact of coalition politics on political parties’ ideologies in Lesotho, 2012-2022”. In H. ‘Nyane and M. Kapa (Eds), Coalition Politics in Lesotho: A Multi-disciplinary study of coalitions and their implications for governance.

Santho, S (2017). “Can Lesotho survive? The political economy of a fragile state”. In M Thabane (Ed), Towards an anatomy of persistent political instability in Lesotho, 1966-2018.

O’Neill, A (2021). “Youth unemployment rate in Lesotho in 2021”, ILO. Retrieved from https://www.

statista.com/statistics/812179/youth-unemployment-rate-in-lesotho/ on 9 October 2022.

Mokete Pherudi is the former head of the Committee of Intelligence & Security Services of Africa (CISSA) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. He has participated in a number of election observation missions in southern Africa and beyond. He has also served as a technocrat in the SADC regional mediation and facilitation processes in countries such as Lesotho, Madagascar and Zimbabwe. Pherudi recently published a book titled Governance and Democracy in Lesotho: Challenges faced by SADC intervention, 2007-2015.