Policymaking lessons we can learn from Africa’s experience with reducing child mortality

A persistent theme within commentary on policymaking across Africa is an emphasis on the “negative lessons” we can draw from policymaking failures. Questions are asked about what led to the negative consequences of policy on issues such as youth unemployment or corruption, with these policymaking deficiencies used as an example of what policymakers should not do.

However, an equally important but less frequently asked question seeks to identify areas where policymakers across the continent have played a role in improving living standards, and asks whether any general lessons about what can be done to better policy outcomes can be learnt from these experiences.

We could term these “positive lessons” to be used when faced by complex problems. One area from where we can draw these “positive lessons” is by analysing how governments, civil society, international organisations and private actors have worked to substantially reduce child mortality in Africa over the past three decades.

Child mortality since 1990

Since 1990, hundreds of millions more have survived childhood globally than in previous generations. Because of this more children have completed school, have matured into adulthood and have started families. These trends have had a significant impact on demographics, economies, politics and societies.

The reductions in the global child mortality rate represent a general increase in living standards – especially in healthcare – which has had a meaningful impact on people’s lives. To better understand these trends, it is worth reflecting on what child mortality refers to.

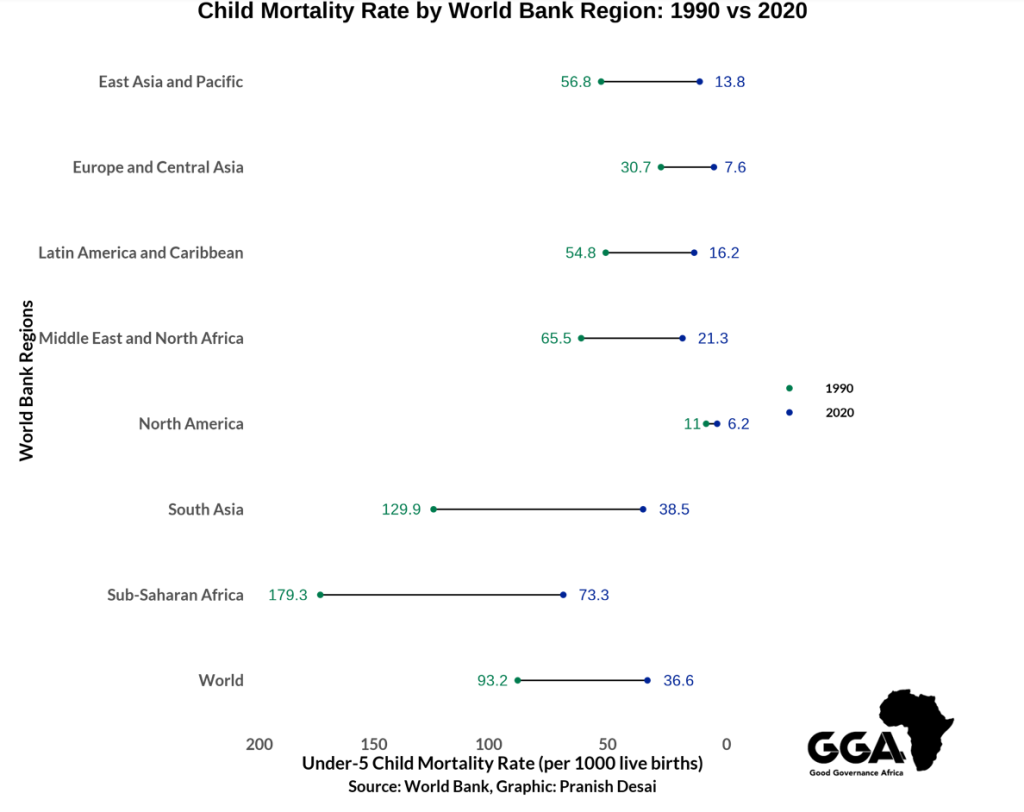

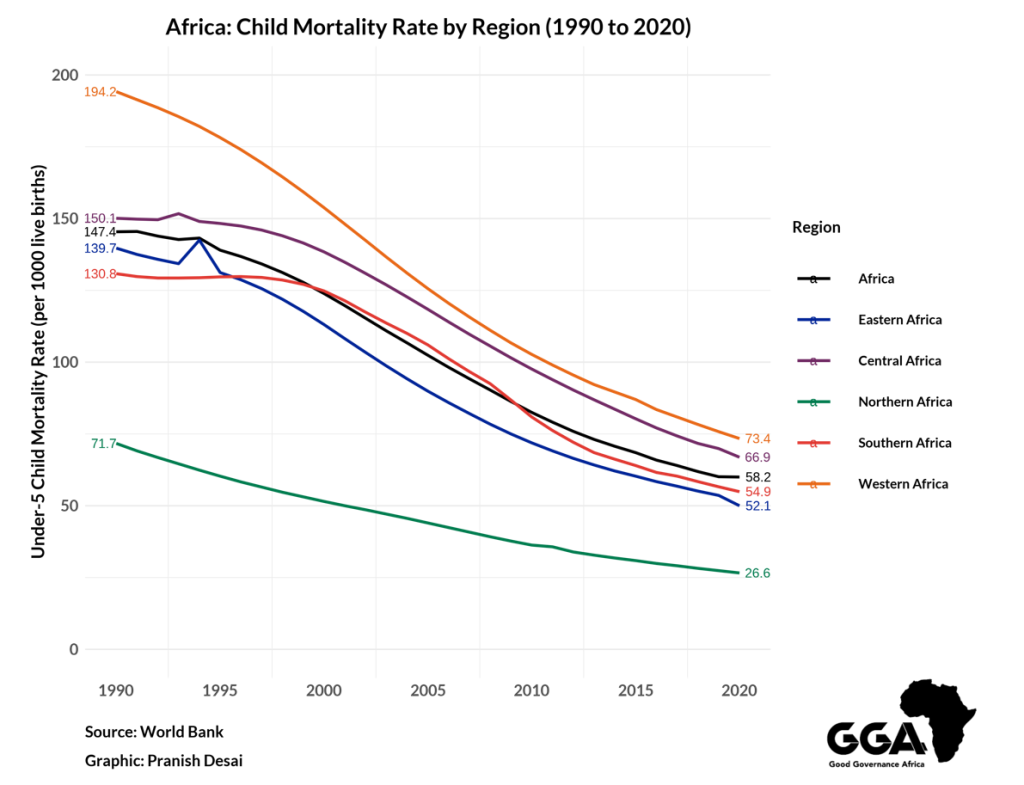

The child mortality rate reports the likelihood that a child perishes between birth and the age of five within a specific society. The rate is measured as a number out of every 1,000 live births. Reflecting worldwide trends, child mortality in Africa has decreased since 1990. While the continent, and particularly sub-Saharan Africa, still maintains the highest average child mortality rate of any region globally, the child mortality rate for this region has declined from 179.3 deaths to 73.3 deaths per 1,000, a reduction of nearly 60%.

A closer look at the trends reveals that the declines in child mortality have occurred across the continent, particularly since 2000. Reductions in child mortality were not as evident in Southern Africa during the 1990s due to the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and the inconsistent policy frameworks formulated in response. An example of this impact is Lesotho being the only country in Africa which recorded a higher child mortality rate in 2020 than in 1990.

By contrast, in 23 African countries, the child mortality rate in 2020 was at least 100 deaths lower than in 1990, while it was at least 50 deaths lower in a further 17 countries.

Though much needs to be done to bring Africa in line with the rest of the world, there have already been widespread improvements in policymaking throughout the continent. As such, continued reductions in child mortality will primarily arise from continuing with and expanding policy directions, as opposed to charting a new course.

How policy helped achieve these reductions

A crucial point in understanding these reductions relates to how policy has changed the composition of the primary causes of death among children under the age of five in Africa.

Notably, deaths caused by diarrhea, malaria and lower respiratory infections (such as pneumonia) have decreased. Moreover, the share of fatalities caused by other infectious diseases such as measles, HIV/AIDS, tetanus and tuberculosis has also declined.

There are myriad reasons for these shifts, but a 2021 report by UNICEF says two policymaking changes are pertinent: a focus on improving access to basic services particularly in sanitation, and the expansion of early-child immunisation programmes.

Improved sanitation – especially enhanced access to clean tap water and better sewage systems – is one of the main reasons for the decline in children suffering from diarrhea across the continent. Since 1990, more than 200 million people in sub-Saharan Africa have gained access to improved sanitary facilities.

A feature of this expansion was the greater policy focus which governments, international organisations and NGOs placed on enhancing basic service provision. The importance of these policies across the continent were highlighted by the findings of a 2017 study which established that a 1% increase in access to improved sanitation reduced the child mortality rate of a country by two deaths per 1,000 live births – mainly by lowering the number of deaths caused by diarrhea.

Enhanced immunisation coverage – especially through early-age vaccinations – has also played a big role in reducing child mortality. The proliferation of specific vaccines to counter diseases such as measles, hepatitis B, tetanus, meningitis and tuberculosis has seen a meaningful fall in the deaths of children from these diseases.

It is estimated that better immunisation coverage helps prevent 4-5 million deaths annually. And while coverage in Africa remains unequal, there is work being done to improve access to these critical interventions.

The lessons we can learn

Four points are particularly worth raising when considering the lessons we can learn from reducing the child mortality rate across the continent:

- An emphasis on improving day-to-day governance – The improvements in access to basic services which have helped reduce child mortality across Africa demonstrate the continued importance of day-to-day governance.

- Evidence-based policymaking – The value of evidence-based policymaking is best seen in the importance of early-childhood vaccinations in the efforts to reduce child mortality. Despite frequent disinformation efforts, governments and other actors have continued to expand vaccination drives due to overwhelming evidence in favour of their effectiveness. The recent decision of Niger’s government to expand malaria vaccinations to the under-5 age group is a case in point of this policymaking principle – especially when one also considers that Niger was the African country which saw the largest drop in its child mortality rate over the last 30 years.

- Building trust at the local level – The importance of trusting local institutions has been decisive in the fight against preventable deaths among children in Africa – especially for early-childhood vaccination efforts. A 2021 study found lower rates of early-child vaccination in Africa were more prevalent in areas where institutional trust was also low. Without local-level trust, it is difficult for governments to maintain the legitimacy needed to act on behalf of citizens.

- Forming a broad coalition of actors – One of the most crucial aspects in the efforts to reduce Africa’s high rates of child mortality has been the presence of broad coalitions across the continent. Governments, international organisations, global NGOs and local civil society initiatives worked together on improving policy on this issue. This has ensured consistent political will when dealing with this problem and has helped with mobilisation required to improve basic services and sustain vaccination drives.

Policymaking frameworks which include these four principles increase the likelihood that living standards improve. In doing so, policymakers can not only ensure that millions more children across Africa will continue to survive early childhood, but also that their prospects for education, jobs, and starting families of their own improve.

Pranish Desai is a doctoral student in political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His core areas of focus are in comparative politics and political methodology, with a specific interest in the politics of Southern Africa. Between 2021 and 2024, Pranish held several key positions within the Governance Insights and Analytics programme at GGA. In these roles, he was centrally responsible for the elevation and enhancement of the Governance Performance Index as GGA's flagship governance assessment tool. Before departing GGA, Pranish also played a key role in the development of our strategic framework for the 2024-2028 period.