In this Africa in Fact edition dedicated to culture, Fred Khumalo paraphrases our mutual friend Mondli Makhanya who, in the midst of a debate with a right-of-centre interlocutor, asserted that, “I am a South African and that’s where it ends”. Much as this position is apt within a national discourse on identity politics, if we zoom out to the continent, Africanness has to be our departure point; for in one simple sense, culture is the outwardly radiating manifestation of our being in the world.

In this Africa in Fact edition dedicated to culture, Fred Khumalo paraphrases our mutual friend Mondli Makhanya who, in the midst of a debate with a right-of-centre interlocutor, asserted that, “I am a South African and that’s where it ends”. Much as this position is apt within a national discourse on identity politics, if we zoom out to the continent, Africanness has to be our departure point; for in one simple sense, culture is the outwardly radiating manifestation of our being in the world.

To elaborate, Max, a cab driver in DC who hails from Ghana, shares the following insight, “African culture teaches us from the earliest days to have respect for other people; you would think that with money and technology we would be happy and content but we have lost that culture. There is no respect for other people.” Culture often portrays more than a colourful aesthetic or funky tone, instead promoting a value base to what we represent, what we do, and who we are in the world. Hence the lament when culture loses its charge.

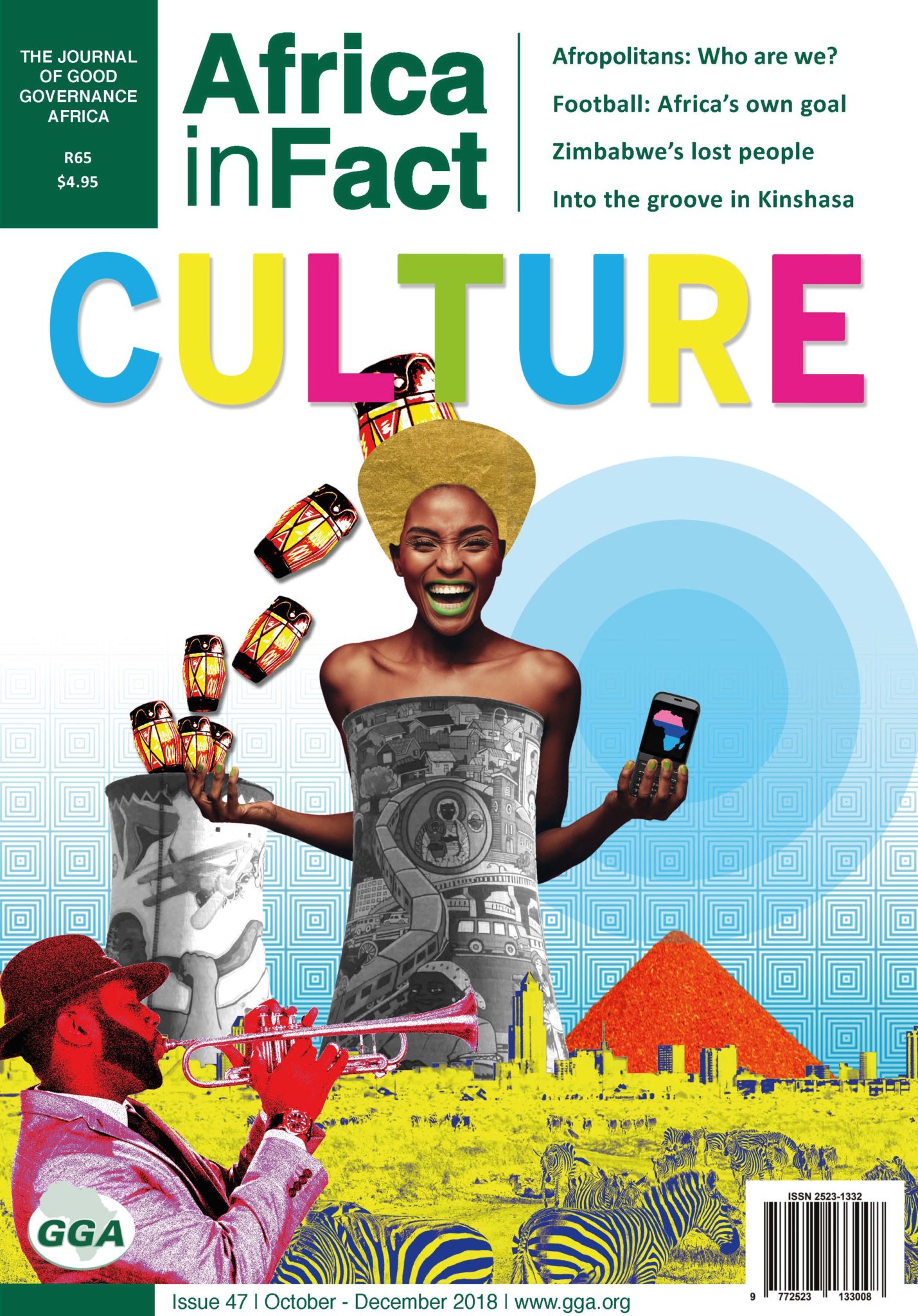

As our readers will appreciate from our zesty cover, however, the manifestation of culture on the African continent, as we have presented it, is all-embracing and flies effortlessly across the spectrum from food to fashion, soccer to the sounds of Afrobeat, religion to the Congolese rumba and beyond. Challenges may abound, but it’s an exciting time to be African.

Recent work events confirm the current fuss over all things African. At the Africa Transformation Forum in Accra, dazzling shades of Kente cloth were proudly worn by overseas delegates, while a more recent event at Ikoyi in St James, London, verified the hype associated with this West African inspired menu of plantains, jollof rice, efo, suya and other culinary treats, with cuisine fit for a lady and a lord; literally. South African wines are increasingly fêted in North America, as confirmed by Cape Classic wines recently wining a prestigious award in the US.

In short, there is increasing traction for Africa’s cultural sharing and export. With this comes the tension of protecting local intellectual property rights and balancing this with an expanding global market of incremental consumers. Nicky B highlights this in a poignant piece on African music, with respect to songs such as Wimoweh and Soul Makossa. Charmain Naidoo picks up on the issue of cultural contestation in her presentation on African fashion, while Anna Trapido suggests that on the foodie savoir-faire front, pitted against the EU’s 837 Geographical Indicator (GI) protected goods, Africa has only four. These inequalities are palpable.

Yet, as Andrew Panton recognises, in Africa the beat goes on, at least in the DRC where music sustains society. And it is not only melodies, food and fashion that take to the stage; African film is a niche market in the industry that holds much potential for development. Verónica Pamoukaghlián tells us that Nigeria and South Africa contribute $1 billion to the continent’s annual GDP. Whereas the former’s production dwarfs the latter’s, in box office revenue the southerners pull in 7.5 times as much, at $90 million.

Analytically, the very notion of culture, which John Kakonge engages in detail in his piece, needs to be retraced back to its beginnings and this necessitates some attention to history. This, coupled to the mantra that “Africa is not a country”, leads Luke Mulunda to suggest that we refer to “cultures of Africa” instead of “African culture” to promote an appreciation of the diversity and magnitude of the phenomena at hand.

Taking history at its broadest reach, we present an article by Delme Cupido on the plight of Africa’s “first peoples” with notable challenges and significant advances to recognise their human dignity before focusing more specifically on the San in Zimbabwe in a provocative piece by Owen Gagare that exposes their difficulties. Keeping with the theme of migrant peoples, Ini Ekott dives into the lives of Fulani pastoralists who since time immemorial have been nomadic and who now face major adaptive pressure in an existential threat to their culture.

In terms of concomitant diversity, we see Khumalo’s “Afropolitan” squaring off with so-called “white” Africans, who are, according to Kevin Bloom, still in the process of negotiating the identity of their Africanness. Meanwhile, Terence Corrigan and Vaughan Dutton find no evidence of a consistent religion-governance nexus, which flies somewhat in the face of intuition given the significance of faith-based traditions proselytised onto the continent and their cultural richness.

Ronak Gopaldas unpacks the “reverse flow” migration of sporting Africans onto the terroir of old colonial masters, with reference to France’s recent victory in the FIFA World Cup, using this as an exemplification of the outflux of some of Africa’s best and brightest human and cultural capital. Tom Osanjo provides the flipside of this coin, discussing the success of ex-pat sports stars back in their home countries, such as footballer Dennis Oliech from Kenya.

After all, our African identity is only the beginning, the rest is what we choose to retain, create, inspire. In January, the world lost one of its most talented sons, the late, great, Hugh Ramapolo Masekela. I still remember him turning to me during a live performance of The Boy’s Doin’ It in England, pointing and belting out “and this Durban boy’s doing it here in Cambridge”. I felt proud of being African and proud of the funky Africa Bra’ Hugh was representing on the global stage. In the face of adversity, racism and inequality, those warm, colourful, cultural strains of Africa streamed out sweetly through his lyrical trumpet on that cold, frosty, northern night. “Africa’s century is only just beginning,” I thought to myself, as I smiled infectiously.

Alain Tschudin

Executive Director

ALAIN TSCHUDIN is a former Executive Director of Good Governance Africa. He is a registered psychologist with Ph.D.s in Psychology and in Ethics. He was a Swiss Academy Post-doctoral Fellow at Cambridge and oversaw the Conflict Transformation & Peace Studies Programme at UKZN for several years. He has broad research and community engagement interests and has worked for various universities in Africa and Europe, with the European Commission, with local and international NGOs, as CEO of a leadership development agency, and as lead consultant for Save the Children and UNICEF, most recently as Child Protection Assessment Coordinator for Northern Syria. Alain has an adjunct association with the International Centre of Non-violence (ICON) and the Peacebuilding Programme at the Durban University of Technology.