Bogolo Kenewendo illustration: Valentina Manente, based on Black Panther © Marvel Studios 2018

Youth – people between the ages of 15 and 35, according to the definition used by the African Union’s Youth Charter – make up more than 35% of Africa’s total population. But in elected legislatures in countries such as Ghana, Uganda and Nigeria they remain under-represented.

In Uganda – where five seats are reserved for youth representatives in a parliament that has grown to include 431 members – just under 15% of those elected in 2016 were born in 1980 or later, while less than 1% were aged under 25.

In Ghana, where greater youth representation and participation has been observed in recent elections, change, as in Uganda, appears to be occurring, but slowly, according to a 2016 article in the Daily Monitor, a Ugandan news outlet. The average age of MPs in Ghana’s parliament who were elected in 2016 is 48 years; the median age of the country’s population is 20.4 years, according to a study this year by the Westminster Foundation.

In Nigeria, nearly 70% of the population is estimated to be under the age of 35, according to Nigerian journalist Orji Sunday, writing for online publication African Arguments – yet people in this age category are nowhere to be seen in the corridors of power. Today, the youngest member of the national parliament is 43.

One major barrier to entry facing aspiring young politicians in some countries is legislation that places minimum age requirements for elected office. This is not the case in Uganda, where the age threshold to stand for office is 18 – the same as the voting age. But in Nigeria, you must be 40 to stand for the presidency, 35 to become a state governor and 30 to contest for a seat in the House of Representatives. All of this existing legislation excludes 18-30 year olds, who have the right to vote in elections, but are barred from any participation in seeking election to political office.

In 2016, YIAGA, a civil society advocacy organisation, took on the challenge of reducing this barrier to entry in politics for Nigerian youth. The organisation’s call for greater youth participation manifested in a “Not Too Young To Run’” campaign, which has garnered significant support on social media platforms in the country, and also made some progress in altering the legal environment, which largely excludes young people. The “Not Too Young To Run” Bill proposed that age restrictions for candidates for the presidency and state governorships be dropped to 30 and to 25 for those aiming for the House of Representatives, and was approved by the National Assembly and 35 of Nigeria’s 36 states. On May 31 this year, President Muhammadu Buhari signed the Bill into law, opening up Nigerian politics to a younger cohort of representatives in elections scheduled for February 2019.

A second major obstacle is the costs involved in competing in electoral politics. Studies carried out by the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD) in Ghana, Uganda and Nigeria have sought to quantify some of these costs. In Ghana in 2016, aspiring members of parliament spent, on average, $85,000 to secure a party’s nomination during the primaries and to contest for the constituency seat. In Uganda, in the same year, parliamentarians quoted outlays ranging from $43,000 to $143,000.

In Nigeria, people seeking to be elected to either house of the bicameral national assembly in 2015 estimated spending a staggeringly high $500,000 to ensure victory. In the words of one aspiring politician: “It got to a point during the campaign that I decided not to keep records any longer so that I didn’t get discouraged.”

“At every stage in our politics a whole lot of money is involved, both at the local and national level,” says Chikodiri Nwangwu, a lecturer in political science at the University of Nigeria. Most young people who would be interested in a political career are recent graduates, and unemployed or underemployed, he says, adding, “(Many) barely get three square meals a day.” The high cost of politics discourages youth from actively taking part in the decision-making process, as well as vying for electoral positions.

Some 65% of respondents to a WFD survey of political aspirants in Ghana agreed that young people are excluded from the outset because they are unable to mobilise the financial resources required. On average, candidates under 30 spent some 48% less than others during the December 2016 election, according to the report.

The challenge of fundraising, particularly for party primaries, which are often highly contentious, appears to be even more acute for young women, who often do not have access to the social networks or personal finance to self-fund campaigns that men do. In more rural areas, social norms are also a constraint.

Nonetheless, young people are beginning to make inroads into formal politics. In 2012 Proscovia Oromait won a by-election to become an MP in Uganda aged just 20, succeeding her father in the role. In 2016, a 23-year-old law student, Francisca Oteng Mensah, made history by becoming Ghana’s youngest elected member of parliament.

However, her father is an international businessman, so she was not financially constrained. In Nigeria, the handful of younger politicians who do get elected into office tend to come from wealthy backgrounds. In Kenya’s 2017 election, John Paul Mwirigi, a 23-year-old student, campaigned on a shoestring budget, using classic door-to-door campaigning. Relying on social rather than financial capital, and combined with growing disillusionment with the political class, he was elected. But these examples are few and far between.

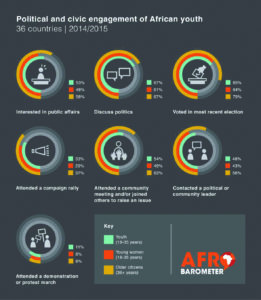

Political apathy among youth across the continent is on the rise, according to a 2016 Afrobarometer study of 16 African countries. It found that just 65% of people between 18 and 35 voted in their respective countries’ last national election, as compared to 79% of citizens older than 35. Young people are even less engaged in civic activities such as attending community meetings or contacting political or community leaders. Such apathy has built up in response to decades of government corruption and failed leadership.

Something similar is clearly also behind young people’s self-perpetuating disillusionment with, and detachment from, electoral politics. Youth might get more engaged if they saw politics as a space that is open to them, but changing that perception requires getting them into political office in the first place. There is also no guarantee that a younger generation of politicians will offer improved accountability and governance when in office.

Something similar is clearly also behind young people’s self-perpetuating disillusionment with, and detachment from, electoral politics. Youth might get more engaged if they saw politics as a space that is open to them, but changing that perception requires getting them into political office in the first place. There is also no guarantee that a younger generation of politicians will offer improved accountability and governance when in office.

During a 2016 interview with the Daily Monitor, Nicholas Opiyo, a prominent human rights lawyer in Uganda, stressed the need for better balance, arguing that while it was “good to see more youth elected MPs … experience and knowledge also comes with age”.

It must be said that age is certainly not a quality in short supply when looking at the leadership in Nigeria, Uganda and Ghana. The average age of the president in these three nations is 74, while the median age of their populations ranges between 15.5 years and 20.4 years. This is not to say that only young people can represent youth, or that greater youth participation in politics would necessarily improve civic accountability and government policy in the short term. But it is critical that young people be enabled and encouraged to take a more active interest in politics across the continent. Improving access to the political system, by breaking down legal and financial barriers, would be just one part of that. Doing so would give the voices of the continent’s young people an opportunity to be better heard, and perhaps a chance to start shaping their own futures.

Jamie Hitchen is a researcher at the Africa Research Institute in London. He holds an MA in history from University of Edinburgh and an MSc in African politics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). He is interested in how informal structures leverage political power and has worked on these themes in Uganda, Ghana and Sierra Leone. He has written for the Daily Maverick, World Politics Review and Africa is a Country.