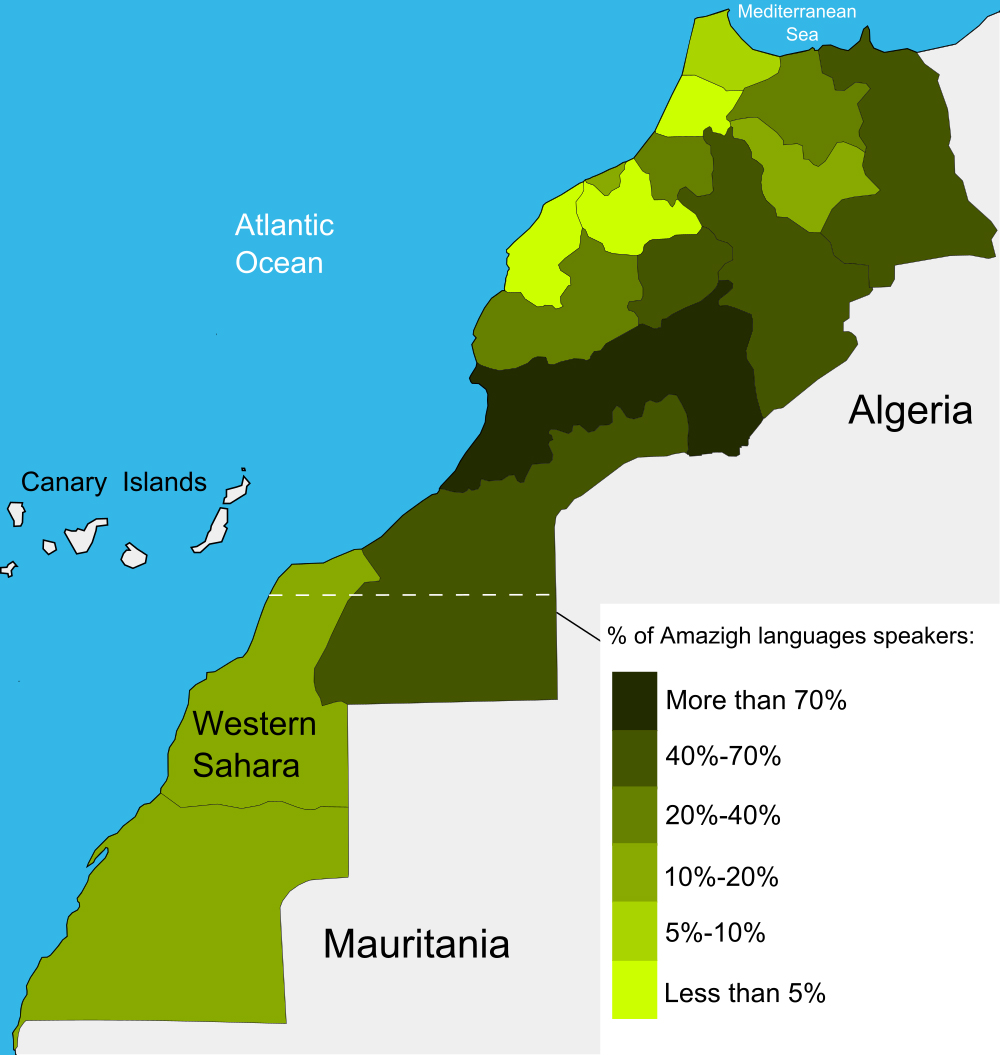

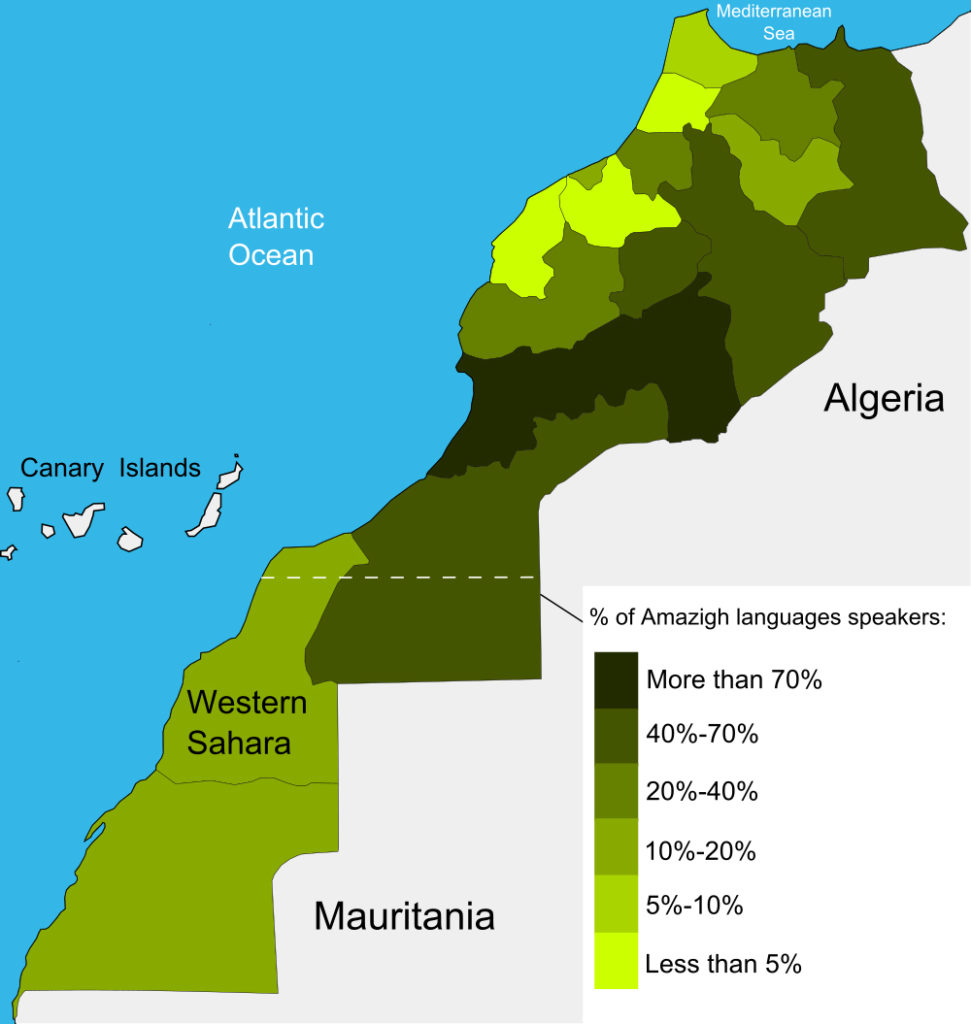

Tamazigh speakers in Morocco. Image Wikimedia Commons

The five-year-old constitution seeks to restore the language, culture and traditions of a marginalised group

Morocco largely avoided the turmoil seen in other North African countries during the Arab Spring protests five years ago, it did not escape unscathed. A popular protest movement known as the “February 20th movement” saw widespread demonstrations in urban areas, inspired by events in Tunisia and Egypt.

After months of unrest, Morocco’s King Mohammed VI promised to extend democracy and ushered in the passing of a new constitution in 2011. As well as promises to hold new elections and deliver social reforms, the constitution made the Tamazigh language—the tongue of the Amazigh or Berber communities, widely accepted to have been the original inhabitants of Morocco—an official state language.

The figures have been contested, but Morocco’s 2004 census declared that around 30 percent of Moroccans speak Tamazigh as their mother tongue.

Yet there has historically been little teaching in the language in Morocco’s schools and, indeed, during the rule of Mohammed VI’s father, Hassan II, speaking Tamazigh was suppressed. Official, judicial and administrative business continues to be carried out in Darija (Moroccan Arabic) and French.

“It has always been the case in Morocco that if you couldn’t speak Darija you were locked out of society. We felt that we had to learn Darija to be a citizen, but we didn’t feel like it belonged to us,” says Amina Zioual, president of the campaign group “The Voice of the Amazigh Women”. “They told us, ‘Come and learn a language which is better than your language … If you want to succeed then you have to speak it.’”

Many Tamazigh speakers live in the mountainous regions of the Rif and the Middle and High Atlas, often in remote villages with very poor roads and, until recently, unreliable electricity and water supply.

Education in these marginalised areas is patchy and, historically, girls were seldom sent to secondary school. Morocco’s overall illiteracy rate remains stubbornly high at 32 percent, according to the 2014 census. The number of people who are unable to read or write is markedly higher in the rural areas—at 41.7 percent, in comparison to 22.2 percent in urban areas.

Giving the Tamazigh language constitutional status is an important step. However, there have been lengthy delays in making it a reality. A draft law covering the modalities of making Tamazigh an official language was finally completed in June 2016, almost at the end of the current parliament’s mandate. The government is on a tight course to get the law changed before legislative elections due in October.

Morocco’s communications minister, Mustapha El Khalfi, stressed recently that “the law is ready to be instituted”. But progress in incorporating Tamazigh into public life is slow, apart from a few motorway signs in Tifinagh, a modern version of an ancient Berber alphabet which was promoted by the king as a compromise between writing the language in Arabic or Latin script.

“The new Constitution promised in 2011 that our language would be official within five years,” says Hha Ouadadess, an academic, mathematician and Amazigh activist. “That

deadline is up, and we’re still waiting”.

So how did such a significant minority — the original inhabitants of North Africa—find their language on a second footing to Arabic? The relationship between today’s Amazigh communities and the state is complex.

The community was originally animist, with some early Christians, and the first Amazighs converted to Islam in the seventh century. In 788, Idris Ibn Abdallah, an Arab who claimed ancestry back to the daughter of the Prophet Mohammed, fled Mecca and arrived in the town of Volubilis near present day Meknes. He was welcomed and made an imam by the local Berber peoples.

While some communities actively resisted the Arabs, Islam’s influence continued to grow. Two of the most powerful Muslim dynasties in the Middle Ages, the Almoravids and the Almohads—some of the so-called “Moor” groups who ruled in the Muslim region of Al-Andalus, the southern part of modern-day Spain—were of Berber descent.

However the Amazigh’s fortunes waned in the 17th century when a new Arab dynasty, the Alaouites, which claimed descent from the family of the Prophet, took power. This is the dynasty from which Morocco’s King Mohammed VI hails.

During colonial times, between 1912 and 1956, the French hoped that using the Alaouites’ religious authority would help them to administer the French Protectorate. “They exploited divisions between Arab and Amazigh,” says Ouadadess.

“It made sense for them to view Morocco as a Muslim, solely Arabic-speaking country.” The perceived exclusion of the Amazigh during this time led to several rebellions by the Berber against the French and later the Moroccan authorities.

As an example, a rebellion developed in the early 1970s in the remote valleys around Imilchil and Ksar Sountate in the High Atlas. It was brutally put down by the armed forces of Mohammed VI’s father, Hassan II, in 1973. For the next 20 years the use of Tamazigh was suppressed, and people could be arrested simply for writing in the language.

Moroccans were only allowed to choose from a certified list of first names for their children, which did not include any traditional Amazigh names.

“For many years these communities in remote mountainous regions were punished through neglect,” says Hicham Houdaïfa, a Moroccan journalist and author of “Dos de Femme, Dos de Mulet” (2015), which documents the lives of women in the High Atlas region. “The state presence was and still is weak, and people live very precarious lives. There are few schools, few clinics, and the people are marginalised. Many of the women live in ignorance and have never been to school; they continue to live in Middle Age conditions.”

“Marginalisation was carried out on purpose by the state,” says Zioual. “The system wants to exclude Amazighs and to Arab-ise everyone.”

However it would be wrong to see the current situation as an outright tension between two different communities. The Amazigh and Arabs have been living and mixing in what is now known as Morocco for more than 1,000 years. Amazigh activists are quick to stress that they don’t consider themselves to be a separate race. Many modern day Moroccans, at least in the urban lowland centres, feel they have a mixed heritage.

Moroccan Arabic is heavily diffused with Tamazigh words and grammar, including a distinct lack of vowels that often makes it difficult for those who speak Middle Eastern dialects of Arabic to understand. Many Moroccan families have several members who speak or understand the Tamazigh language.

King Mohammed VI has taken some steps towards recognising the Amazighs’ role in Morocco’s history. Amazigh activists say the most important thing for them is for the language, culture and traditions to be respected.

“Recognising our language is a great first step,” says Ouadadess. “It had to happen. Amazigh are tired of waiting. Let’s just hope that in the coming years we can find a good way to do it; to see our courts speaking Tamazigh, and to see our children being taught in their own language.”